My name is John (Jack) Russell, born October 27, 1922.

Since I am now 82 years old and since I am no longer active in the military,

I thought it would be safe now to put together a brief tale of my activities in that greatest war (WWII).

Most of these stories my children have heard in their growing up years, so I write mostly for their children who

may well have difficulty swallowing much of this.

I can’t promise to the accuracy of all details, since I’ve no doubt forgotten more than I’ll remember,

but here it is anyway.

I spent three years more or less in the Army Air Corps (now known as the U.S. Air Force) finishing up as a pilot

with 268 missions, 677 combat hours, 3 battle stars, 3 Air Medals, and 2 DFCs, according to my flight records.

But knowing how loose the clerks sometimes worked in those days, I wouldn’t want you to hang on their every word.

Those years became a deep part of me that would never stray far from my memories, and they were surely a mixture of

fear, excitement, and a huge dose of boredom.

This is how it happened.

I was an engineering student in my second year at Grove City College when the Japs hit Pearl Harbor.

Till that time the war had little meaning to us kids, but then things changed drastically.

Some guys left school at once, rushing down to the nearest enlistment office, but most of us didn't quite see it

that way. The draft, of course, had been in effect, but those of us in scientific studies were exempt.

The war brought shortages and rationing of many things, such as gasoline, which limited travel, so my junior year

I transferred to Carnegie Tech, the travel time to Pittsburgh being much shorter. As expected, classes were

indeed more difficult there, and especially so with the war constantly on my mind, so on October 2, 1942 I enlisted

in the Army Air Corps Cadet program. I was nineteen years old.

All through my early years I had loved airplanes, built all sorts of model planes, read endless comic

books keyed to the World War I flying aces, and dove into the development of the newer planes.

I really wanted to fly, and with the required two years of college completed, I qualified for the Air Corp Cadet

program. The rest of my first semester in college was a disaster, so I didn’t go back for the second semester,

waiting instead for the Army to call me. Meanwhile, I worked in a steel mill making artillery shells and dreaming

of flying until February, at which time I was ordered to report to Pittsburgh for induction.

Once there, we (me and another hundred or so guys) were instructed, lined up, and loaded into a

railroad car. Now I was sure that this was a common thing happening every week, so how come newspaper cameramen

surrounded us? I heard later that we weren’t the big attraction, the center of attention being Bill Dudley, the

star running back of the Pittsburgh Steelers who was now one of us. We boarded the train carrying one allowable

small bag containing one change of underwear, toothbrush, and shaving gear, and anything else you thought you had

to have.

Now we were on this train, in this car, for two and a half days, headed south as though going on a

vacation in the winter, except for sleeping on the seats and only getting off when the train made station stops to

feed us. When we finally arrived at Basic Training Center #9 in Miami Beach, we were a mess and missing a few guys

who stayed behind at the last stop. I guess they really liked the girls who brought the food.

They then marched us to the Lord Baltimore Hotel, where we were to live for the next eight weeks.

My group from the train was billeted on the fifth floor, but of course the elevators were not running – so we were.

The hotel kitchen was not in use, either, so we were given mess kits (steel dish and cup) that were filled as we

lined up outside the hotel. At that time we also found out that the army was short of the necessary clothing for

newly inducted privates. We lived our first three days of Army life in those dirty civilian clothes.

What was even worse was the fact that some guys didn’t properly wash their mess kits in the boiling water barrels

after eating and ended up with dysentery. It was a pitiful display of army discipline to watch these guys break

rank when marching through downtown Miami and run for the nearest hotel wash room.

But we survived these shameful experiences.

The summer uniforms arrived, and we went through army basic training with thousands of other

privates, most of who were soon shipped overseas. We came from all walks of life, so this army way of doing things

was harder on some more than others, but as I recall there were three outstanding things that bothered me.

First, because we were in Florida, they issued summer uniforms in the winter, and when they roll-called us at 6 AM,

and when they quite often at 3 AM called fire drills just for practice, we felt like we were going to freeze.

Second, they drilled us for hours on end in the hot Florida sun without supplying us with face protection, causing

the Yankee winter skin on our noses to badly burn. And thirdly, it rained every day at four o’clock, thereby soaking

our WWI putees (leggings) which then dried and shrunk, cutting off circulation to our feet.

Marching on dead stumps is not only difficult but extremely painful.

Remember, we were still civilians learning to play soldier, which sometimes became so obvious.

One good example of this: our group was periodically given the job of patrolling the beach at night to catch

German spies sneaking ashore from U-boats (it had happened). Of course, such duty could be boring, so one guy made

it more interesting by smashing his rifle – he said gigantic crabs were attacking him and he fought them off with

his rifle butt.

INTRODUCTION TO THE WILD BLUE

Fortunately, they transferred the future air heroes out of Miami and sent them to various colleges for

brain training, since the two-years cadet requirement had been changed and some of this group had had no college.

My assignment was to Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, where I attended classes in basic algebra, physics, and

mechanics. Here we were also exposed to our first airplane rides and instructions. It was a most wonderful and

frightening experience for me, although I did not do very well; in fact, I scored poorly in the Piper Cub.

Several of the students were worse off in that they became airsick on takeoff. The instructor told them to eat a

lemon an hour before flying and their problem would go away, and it worked. Anyway, living here was fun: no pressure,

little army, and college girls; but for us who had college backgrounds, this training was shortened to four weeks.

THE REAL WORLD

We were transferred to the Air Corp Classification Center in San Antonio, Texas, where we were subjected

to every physical, mental, and psychological test that was ever devised. After a week of this, they graded us and then

asked us to make a choice: pilot, navigator, or bombardier training. Since my first hours of pilot experience

discouraged any thoughts in that direction, I opted for navigator.

In typical army fashion, they ignored my wishes and sent me to nine weeks of pilot pre-flight school,

which was also in San Antonio. Here we were taught the theory of flight, meteorology, Morse code, enemy aircraft

identification, navigation, and basic officers training. When not in class, we spent many hours in physical training,

the most hated being the long cross-country runs over very difficult terrain, some part of which required wearing a

rain coat and a gas mask. They exposed us frequently to tear gas to thwart those who slipped off their masks during the

run. It was a crying experience. Naturally, some guys found a way to cut across the marked trail, a detour

considerably shortening the run. This was thwarted by having a man at a strategic position giving out buttons that

were collected at the end of the line. No button meant repeating the run. The barracks, as expected, were filled with

bunk beds. Some were assigned to the bottom and some to the top. It just so happened that one guy having a top bunk

also seemed to produce a large volume of internal gas and really enjoyed teaching the rest of us how to make like a

human flame thrower. This went on until one backfired, which ended that kind of fun.

It wasn’t long after we started here that we were told that we who lived on the second floor of the

barracks were the lower class, and the group who started four weeks ahead of us, who lived on the first floor, were

the upper class. Now, our group all came from Yankee country, whereas the other group called Georgia and Alabama home.

The Civil War had never really ended for them, and they had nasty fun with us many nights after lights out, some

experiences rivaling that of Japanese prison camps. Another exciting outing occurred in one of our six-man two-hand

touch-football games. I had the questionable opportunity to block Bill Dudley and never knew anyone could hit that

hard. Pre-flight ended with one glorious gathering of all the Cadets on the parade ground complete with very high

ranking officers on the raised reviewing stand. We were broken down into barracks units, formed four abreast, and

filled the parade grounds. It seemed that we stood for hours in that hot Texas sun while the groups formed up and

speeches were made. I noticed several men in the next group over passed out from the heat; they had to be carried

off to a shady place. The guys next to me thought that looked like a good idea, so after a brief, whispered discussion

as to who would take the fall, we too found a way out of the heat. We did get back in formation in time, however,

to pass in review to the beat of the Air Force Band.

PRIMARY FLIGHT TRAINING

FAIRCHILD PT-19

FAIRCHILD PT-19

|

On completion of the nine-week Pre-flight school, we were sent to do primary pilot training at a small

airfield in northeast Texas called Jones Field, in Bonham in the Red River Valley. The primary training planes were

PT-19's, with front and rear open cockpits, no radio, no fuel pump, no starter, and a wooden propeller, but each did

have a hose and a funnel under the seat (called a relief tube, which in the beginning blind fear caused to be used

frequently). Strapping on a parachute was necessary before climbing into the cockpit.

The seats were made to allow the chute to act as a cushion. I came to really appreciate the security of my chute when

the instructor turned the plane upside down on my first flight and I realized that the only thing between me and the

ground was my safety belt. The instructors were civilians with Army pilots giving the test flights.

Physical training and classes continued, but usually we had at least one hour each day of cockpit time.

The student had the front seat and the instructor the rear.

Since we had no radio, our flying helmets contained copper tubes to each ear.

These were connected to rubber hoses that ran back to the rear seat, at which point they were connected to a funnel,

The first earphones

The first earphones

|

thereby allowing the instructor to speak to the student. However, on occasion, the instructor would bang the funnel

against the side of the plane to spoil your concentration during a difficult maneuver. The plane had dual controls,

so that the stick and rudder petals moved together in both front and rear cockpits. It was not unusual to have the

stick suddenly rattle back and forth painfully between your knees, another way of breaking the student’s will.

This was often followed with bad-name calling and swearing. All these actions were part of the instructor’s goal to

teach us to keep our cool regardless of external circumstances. Unfortunately, some students lost their tempers and

once back on the ground, punched out the instructor. Of course, that was then their final flight.

Now there were three major goals that had to be met before graduating from primary school.

First, you must solo (fly alone) within a set time, usually after eight to twelve hours of dual instruction; second,

you must fly correctly a series of aerobatics with an Army test pilot (slow rolls, snap rolls, loops,

split S. chandells, immelmans, and hammer heads) during which time he would invariably and without warning shut down

the engine, forcing you to go through the proper procedure of landing successfully on a farmer’s field; third, you

must land dead-stick (throttled all the way back), coming in over a high pennant-bedecked clothes line and being on

three wheels within two yellow markings on the runway. All landing procedures required entering the airport traffic

pattern on the downwind leg at a specified altitude, making a right-angle turn at the proper distance from the runway

for the crosswind leg, then turning into the wind for the final approach. This test required the cadet’s judgement on

when on the crosswind leg to shut down the engine. Once done, the throttle was not be touched again. For this final

The parachute was made to fit into the seat.

The parachute was made to fit into the seat.

|

test, we were given three tries to make it to stay in the program and not be washed out. One kid on his desperate third

try saw that he would again overshoot the lines so pulled straight up, stalled out, and dropped straight down,

collapsing the landing gear. He jumped out of the wreck and pointed to his position within the lines.

They had to pass him.

Well, I would say this for primary. Once you’ve gotten over the initial fear of flying, throwing this little airplane all over he sky was pure pleasure, so long as you remembered to hand-pump gas to the engine when flying upside down. I did forget to do this one time during a hammerhead, and the engine stopped dead. The plane immediately began to fall slowly, tail-end first, then fast enough to give me rudder control, so I could spin straight down. With no built-in starter, the only possible way out was to dive with a dead engine fast enough to move the propeller, which restarted the engine. It worked. You just learned to do what you had to do – like the time I flew out of my practice area and did not know the way home. The only solution was to find a railroad track, follow it to the nearest town, then fly low past the railroad station reading the name of the town. It worked, too.

BASIC FLIGHT TRAINING

Nine weeks of primary was complete, so it was on to Basic Training School at Perrin Field, not far from Dallas.

The aircraft here were BT-13s with front and rear seats but enclosed in a glass canopy.

These planes were equipped with starters, fuel pumps, radios, and, of course, relief tubes.

They told us that these planes had heaters, but I think they lied, because even with heavy fur-lined boots, my feet would go numb.

BT-13 VALIANT IN FLIGHT

BT-13 VALIANT IN FLIGHT

|

This was a much heavier plane with a more powerful engine that sometimes shook the plane badly, evolving the name of Vultee Vibrator. Classroom work, physical training and more army officer education continued. Flight instruction took us into the use of the gauges and dials on the instrument panel, as we were to learn to fly blind. Night flying began, first with practice take-offs and landings, then with three-legged cross-country flights. One plane crashed. In order to protect our night vision before taking off, they sheltered us in a dark room with only a few red

lights, then partially covered our eyes on our way out to the planes. To find our way from one city, or airfield, to the next at night was necessary to fly the light lines. These were strong lights set on very high poles several miles apart, which on a clear night laid out a straight line visible for many miles ahead. We did wonder just how we would find our way if fog rolled in. Specially equipped planes were used to teach us how to fly blind. The front cockpits in these planes were completely enclosed, allowing no view through the windshield and causing complete dependence on the instrument panel. Scary at first. Now, Perrin Field was a complete army base with all instruction coming from army officer pilots, so discipline was more rigid. There was a set ritual relating to a checklist that had to be followed each time we flew dual. One time I forgot to check my fuel gauge before take-off, so on landing I was ordered to take a walk completely around the field with my parachute in place, hitting my bottom. A very long walk and a very impressive lesson. But we did find time for some fun stuff. The terrain for many miles around Dallas was absolutely flat ranch land. Once in awhile, it was a challenge to fly to the ground, jumping over the fences as they came up. Stampeding the large herds of cattle by bombing them with pop bottles was not unheard-of, either. Another fun thing was marching in the big parade with a great army band on November 11 in Dallas with all those other soldiers. Otherwise, the nine weeks passed, and I did all right in basic so moved on to Advance Training in Ellington Field, outside of Houston.

ADVANCED FLIGHT TRAINING

I had opted for twin engine training hoping to end up flying a twin engine fighter ( P-38 ), and this was the school I thought for that. The aircraft were AT-10's with side by side seating.

BEECH AT-10 "WICHITA"

BEECH AT-10 "WICHITA"

|

You flew with a partner, either an instructor or another cadet. Sometimes we were paired with another plane

flying in formation, playing catch, or dog-fighting, but much of the time was spent flying at night or on cross- countries using the radio beams to guide us from one airport to the next even landing at New Orleans.

Since Ellington was on the Gulf coast, weather could change very quickly as it did during one of the night flights. We were a half-hour out on a three- legged cross-country when the tower called to all planes to return immediately, as the dew point was just about now. Suddenly, we were beginning to fog in and fortunate to get back and find the field through the developing mist. We heard the next day that planes were scattered on fields for miles around. Some didn’t make it. Besides flying, we were also taught how to properly use a parachute by jumping from a chute tower and were exposed to the effects of low air pressure at high altitudes by being locked in a decompression chamber while the air was pumped out. As we reached a simulated 25,000 feet, an old basketball injury (bone chip) caused nitrogen bubbles to collect at that point on my leg, causing a great swelling and much pain. I had to be quickly brought down from the artificial high altitude, and from there on I was limited to flying at lower altitudes.

Geri - The Love of My Life

Geri - The Love of My Life

|

NOW, THE FUN BEGINS

And so we graduated on March 12, 1944, class of 44C, with a total Cadet flying time of 207 hours. It was a grand ceremony as we received our silver wings and our officer bars. We were then given leave to go home. Since I had not been home for over a year, it was a truly wonderful reunion with my family and my friends. Pilot’s silver wings were not a common sight back home, so my brother took me to his home to introduce me to his many sister- in-laws, especially the unmarried youngest (and most beautiful) one who obviously was not impressed with this dashing young officer. I married her after the war, so I won out in the end.

LOOKING FOR A JOB

As we returned to Ellington as officers, we were told to find quarters in town (hotels) and to check the bulletin board each morning for our new assignments. Each day I saw a number of new pilot listings covering bomb groups all across Europe and the Pacific, until finally there were but a dozen of us new pilots left with no place to go. As time went on, we became concerned that we were going to stay stateside, perhaps as instructors, so we finally sought out someone who should know the score. However, all we got from him was that we were being held back to receive a special assignment. We knew then that we were not to stay in Texas, but since we had been there the better part of a year, it would be missed. During our training, we stayed but nine weeks in each location, all in Texas, and they all differed widely from each other. San Antonio was a mixture of nice and nasty; visits were only allowed in daytime and never were we to go into the Mexican ‘Casbah.’ Too many cadets had been knifed there. Bonham was a small farm town that had been overrun by would-be flyers for some time, but the townspeople still occasionally created various weekend activities for a chance to eat home-cooked food and meet the local girls. Perrin was in a more congested area, so there was more to do with spare time (movies, USO dances, and good cafés). Houston, however, was a jumping city, thriving on oil wells and refineries, so plenty to see and do in that town – although we didn’t really see it until we graduated and waited and waited to be assigned. Of course, Texas then was nothing like Texas today.

THINGS GET SERIOUS

DOUGLAS C-47 "SKYTRAIN"

DOUGLAS C-47 "SKYTRAIN"

|

On April 20 they loaded us on a plane and flew us to Bowman Field in Louisville, Ky. As we circled the field, I looked down with mixed feelings at the rows of C-47 transport planes sitting on the ground as I saw my hope of flying a war plane disappear.

Upon landing, we were taken to the administration building where we signed in. Surprisingly, they told us that they were not ready for us, and that this was the to be the formation of a new group known as the 1st Combat Cargo Squadron of the 1st Combat Cargo Group, and we should take a week leave. So back home again it was, but on returning to Bowman, we still faced a lot of confusion as they tried to put it all together in a very short time. Crews were formed with one experienced pilot and one beginner. I was teamed with Henry Myers. Some of the older pilots had been drawn from assignments that I considered high priority and indicated the importance of this group, but we still had no knowledge of why or where we were going. First training flights began May 2 and we flew eighteen days that month, mostly becoming familiar with the characteristics of this remarkable airplane. We flew with gross overloads (nine tons), sometimes landing with one engine shut down and taking back off the same

way.

The Pilots of 904

The Pilots of 904

|

We were given permission and told to practice flying low, so we flew cross-country a few hundred feet above the ground.

Kentucky is mountainous, and we flew the valleys up one and down the other.

A few of us got shot at as we passed over stills making moonshine; they must have thought we were revenuers. Best fun was flying down the Ohio River just above the water, then over a Cincinnati suburb where a man was raking his grass. He threw the rake in the air and dove to the ground.

Louisville was an interesting city with lots to do, especially around Derby time, but without ready transportation we were limited to an area around the field. We solved this problem by buying a used convertible that we fueled with high-octane aviation gas. On weekends we were given the plane to fly wherever we choose to go, so long as we put a required number of hours in the air. One weekend I choose Pittsburgh as one base, following Chicago and Cincinnati. I called my father before leaving Ohio and gave him a time to meet us at the airport in Pittsburgh. As we approached the field, I took the plane down quite low, flew down my home street, buzzed my house with the engines wide open, then quickly climbed and went in and landed at the airport. My father told me later that our appearance that day broke the record for bond sales in Charleroi.

Now flying wasn’t everything. Training also included playing soldier. We flew into Ft. Knox and spent three days on the ground in infantry gear, eating field rations and making do with only bare essentials. We even got into a mock battle with all sorts of explosions, rifle and machine gun fire, but flying was our reality. We did all things possible with that airplane, but it took taking a trip over the mountains of West Virginia and getting caught in a tremendous thunder storm to develop an appreciation for how well this plane was put together.

GOODBYE, USA

On July 30, 1944, we received orders moving us out, but before we left town, we put on a massive air

show of twenty-five airplanes flying in formation.

After the big show – and it would have been even bigger if Henry would have allowed me to hook up a smoke bomb under

one wing – we boarded a train to pick up new planes in Ft. Wayne, Indiana.

We then flew to Bangor, Maine, where we were properly instructed and equipped for our journey overseas.

| 2nd Lt. Henry W. Meyers, Pilot |

| 2nd Lt. John W. Russell, Co-Pilot |

| Sgt. Norbert J. Eckel, Crew Chief |

| Cpl. William J. Caldernick, Radio Operator |

| 2nd Lt. Charles T. Griffes, Passenger |

| 1st Sgt. Perry A. Withoff, Passenger |

| S/Sgt. Nanol A. Alise, Passenger |

| S/Sgt. Arthur E. Armitage, Passenger |

|

|

|

Crew and passengers of C-47 No. 43-15904 for the trans-Atlantic flight.

SEE ORDERS

|

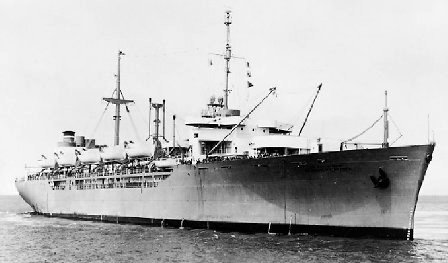

The squadron consisted of twenty-five planes filled with all the personnel and equipment necessary for an independent

operation, but we still had no knowledge of our final destination.

What we did know was the fact that we were preparing to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in an overloaded two-engine

airplane which had had the high speed propellers replaced with paddle props (more suited for low speeds without

stalling).

The fact that they also worked all pilots through Link trainers (blind capsules fitted as an airplane cockpit) in the

landing procedures of a very small island known as the Azores was also unsettling.

The morning we left Bangor, we were given sealed orders and flight details which were not to be opened

until over open water (Tenth Air Force – India, Burma).

Of immediate concern to us was the presence in the body of the plane of two large pressboard cylinders full of high

octane gasoline, metal pipes, and a pump with instructions on how to transfer fuel to the wing tanks as they emptied.

That settled the problem of how we were expected to make it over all that ocean. It would have been less of a trip if we could make Africa from Florida, but August was the hurricane season and that would have been too chancy. To shorten the trip as much as possible, we flew first from Maine to Gander air base in Newfoundland, then the next day halfway across the ocean to the Azores. As the time approached to transfer fuel, I looked down at the ocean from nine thousand feet and imagined what a difficult time it would be trying to find a very small body floating in a life vest. As it was, it was a needless worry.

Our squadron airplane crew did not include a navigator, but fortunately, we were loaned a navigator to take us across an ocean where there were no landmarks or radio beams and where fuel was limited to not much more than the nine hours it took to get us there. Since most of us (nine) on this plane with internal gas tanks were smokers, it was a mighty long flight. The paddle props did not give us an airspeed of much more than a hundred and fifty miles per hour, though we did have help from the westerly winds. Each plane was assigned three pilots, so we took turns allowing for breaks. Like Columbus, the navigator kept us on course by taking sun shots through the glass dome on top of the plane, and brought us right in on the island. All twenty-five planes, which had taken off with a ten-minute separation, arrived safely, although one pilot arrived a little off schedule as he went down low and off course to follow what he thought was a submarine. It was really a whale.

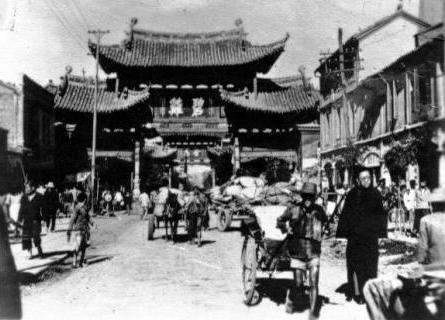

HELLO, NORTH AFRICA

The next leg of this over-water journey was from the Azores to North Africa with a flight time of seven hours. After a good night’s sleep and many pre-takeoff cigarettes, it was an uneventful flight. We landed at an airport in Marrakech, French Morocco, not far from the well-publicized Casablanca, on August 12. Accommodations were in the small local hotels. These American kids were suddenly aware that they were definitely in a foreign country; the food was strange, the language like we had never heard before (even in Western PA), and the bathrooms had three pieces instead of the usual two (the third was a French bidette, or so I was told). The squadron spent two days there getting flight orders and instructions for the next leg of the trip.

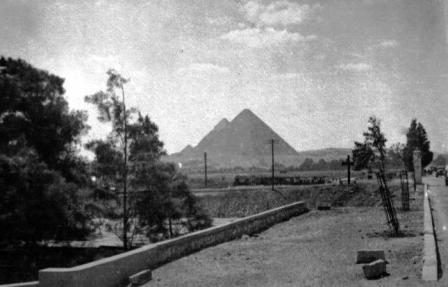

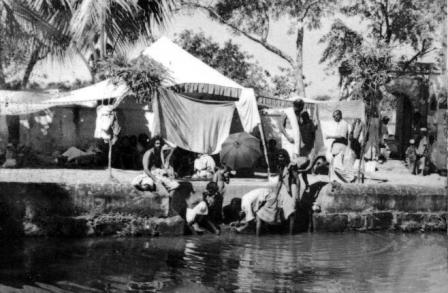

A sandstorm caused a one day delay in the trip, enough time to see and photograph the sites of Egypt.

A sandstorm caused a one day delay in the trip, enough time to see and photograph the sites of Egypt.

|

We were in Arab country and from what we saw of our flight schedule, we would see all the countries of North Africa that bordered the Mediterranean Sea.

On April 14, we refueled in Algiers, then flew on to overnight in Tunis, which is a large seaport.

As we approached the city, an American fighter plane suddenly appeared and challenged us, probably because the harbor was filled with a great number of invasion-force ships. I quickly loaded and fired the scheduled flare and sent him back home.

All the countries along there were French possessions, but as I toured the city, I noticed a number of small children here in Tunis with blond hair and blue eyes, no doubt the result of Rommel’s long German Army occupation. Arriving in Cairo, Egypt on April 16, we were told we would lose one day waiting for a sandstorm to clear at our next stop. Not at all bad since the delay allowed for some sightseeing and picture taking. However, skimming over the tops of the pyramids while flying in satisfied my curiosity in such things. Better was the fact that Cairo was still very British and European. We stayed at the world famous Shepherds Hotel and enjoyed their open-air nightclub.

HELLO, ASIA

Too soon this ended, and we took off for a place called Abadan at the southern tip of Iraq.

It was so hot there that the barracks in which we slept had no windows and double hollow walls filled with straw

through which water constantly flowed.

The next morning, August 19, we left for Karachi, India, a large seaport on the Arabian Sea.

As expected after landing, a jeep pulled up to take us to the operations center.

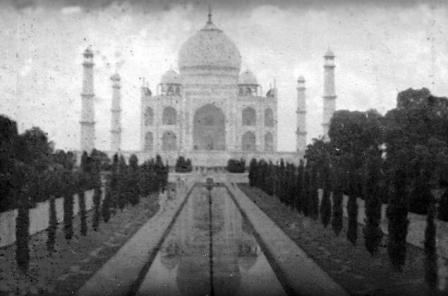

THE TAJ MAHAL

THE TAJ MAHAL

|

What was not expected was the fact that the sergeant driving the jeep was a guy who I grew up with but who had moved

away in high school.

We stayed at this base an extra day, and my friend who had been in India for some time gave me quite an education.

Now Karachi is located near the western border, and our final destination was on the eastern edge of India, some

sixteen hundred miles away, so we stopped at Agra for an overnight and visited the Taj Mahal.

This would be our last contact with the civilized world as we knew it for some time, since the next stop

would be our home base. At this point, we had not been educated as to what to expect at our landing field in Sylhet,

but it was clear as we flew over that this situation was about to resolve itself.

First of all, there was no active radio tower to direct us in; secondly, there was only one landing strip cut into the

surrounding jungle; and thirdly, we were in the middle of the monsoon season and the corrugated metal strip which made

up the single runway was under water. How deep was the question. There was no doubt, of course, that the whole

squadron would put down here; we had no other choice.

The big question was who would be the first one to land on the water with unknown depth, but once the first plane

successfully landed, all took their turn going in. Although most of us were at a loss as to what to do next, the

Major in command had obviously been instructed and shown on paper the layout of this jungle base, which we found out

later had not been occupied for three months.

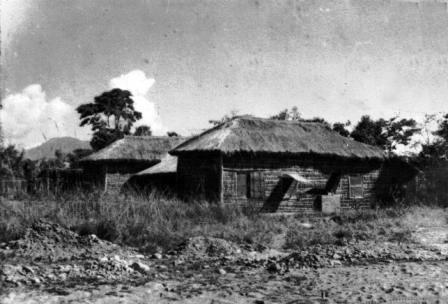

Eastern India under monsoon water.

Eastern India under monsoon water.

|

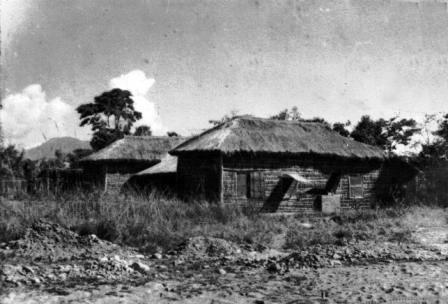

The twenty-five planes carried everything we needed to survive, but of greatest importance at this time were the jeeps and trailers necessary to take everything we owned through the mud and rain to our new quarters: thatch and bamboo huts in a semicircle a quarter mile away. This was not at all what we airplane jocks expected, but even more surprises were coming.

First arrivals at the campsite found several cobras resting on the roof, then later on, a cobra coiled up on his barracks bag. After unloading the basics, the cooks put up a shelter and prepared our first dinner in the jungle, which included a piece of meat. We lined up with our mess kits as we did on our first days in the army. The guy in front of me filled his and had begun to walk away when a big bird came out of nowhere and took the meat right off his plate. Already, I didn’t have a good feeling about this place, and more unusual experiences were yet to come.

We slept naked on our rubber air mattresses, which we covered with a sheet and enclosed in a mosquito net.

This camp had no electricity and no running water, but there were many other things running around the camp at night.

August in Assam meant monsoon (almost constant rain, over four hundred inches in the season), heat, mud, and giant mosquitoes.

Three of us lived in this hut with a thatched roof, fully furnished with all things made of bamboo including the ‘springs’ on the bed.

Three of us lived in this hut with a thatched roof, fully furnished with all things made of bamboo including the ‘springs’ on the bed.

|

You learned not to over-drink during the day, because you sure did not want to leave the basha (hut) after dark. Other things of interest – a banana tree nearby which attracted beautiful moths as big as your hand and tarantulas of the same size, giant chameleons (lizards) of many colors running on the walls, and, of course, large jungle rats which came in every night looking for food. These things we learned to live with, but waking up in the morning after sleeping in a pool of your own sweat that collected on the rubber mattress was hard to accept. The humidity was such that any leather item not worn for a day would be coated with a green mold. We were also told to shake our boots upside down to be sure that a very poisonous small green snake didn’t spend the night sleeping in there. Relief from this came only by flying hopefully above the rain clouds and into the sunshine and into the much cooler air, and fly we did, almost every day. Since we had no refrigeration, we took our beer with us to cool it down. Of course, we had to drink some of it while it was still cold.

When we first arrived at Sylhet, we knew very little of what we were to do and how to go about it,

but we knew that time would correct that. First of all, we were told to taxi the empty planes into parking places

notched in the jungle known as revetments. This, I suppose, was to keep us hidden from enemy planes, although only a

few days into our arrival we became aware of the fact that they knew we were in place – since we were an item on the

Tokyo Rose morning show.

C-47's concealed in revetments notched into the jungle.

C-47's concealed in revetments notched into the jungle.

|

WELCOME TO THE BURMA HILLS

We also were told that when scheduled for takeoff in the early morning hours (while still dark) that a jeep shining a flashlight would lead us back onto the single runway. We would then just turn to the proper compass heading and go, depending on the landing lights on the plane to light our way since the field had none. Our purpose here was to work with the British ground forces in the Burma hills, supplying them from many small airfields along the Indian border. Each day a Brit would show each crew on a map the drop zone to be worked that day. He also mentioned that the chances of surviving should we have to parachute out were not good. Solid tree coverings would hang up a chute, and the animals and headhunters would do the rest.

The procedure went as follows: the small door was removed from the plane, the material to be dropped was loaded, the three men assigned to work with us got aboard, and we took off. Quite often the flight would not be more than thirty minutes to the clearing, which usually was marked as designated with old parachutes. The three men working in the back would stack one load in the doorway, then one would lay down on his back, placing his feet against the boxes on the bottom while the other two would stand on each side of the doorway. We would fly over the zone as low as possible and at the right moment buzzed the loaders to push out the boxes with their chutes. Some of these missions required as many as nine passes to empty the plane. Most of the bundles had parachutes attached, but some were free falling.

Very few of the zones were on level ground, for most of Burma was mountainous – so the pullout following a drop could get exciting. In order to prevent the possibility of blowing a chute onto our tail, the engines were throttled all the way back to idle when the signal was given to dump, then pushed to max power to pull out. We knew that if one engine failed at that time, we would be over on our back and into the hill. Good engines. Because of the hilly position of the clearings, we sometimes had to make rather sharp turns, but we knew the crew in the back had attached safety ropes. During one drop, we heard and felt an impact on the tail and were sure we had a man dangling alongside, but as it happened, one free-fall piece hit the stabilizer and cut the rubber deicer boot, which was flapping against the elevator. Another thing that made this kind of work interesting was the fact that there were many enemy soldiers below us, and they were against our supplying the British army. When machine guns on a hillside seemed to be looking into our face, we changed the direction of our approach to the drop. All of these flights were made singly and without fighter escort, and although much of the Japanese air force had been cut back (sent to the Pacific), there were occasions on which supply planes disappeared into the jungle. It had been said that there was a Jap fighter base a hundred miles or so away and their radar could pick us up if we flew above the hills.

THE MISSION

Assigning a target

Assigning a target

|

Flying the drop zone with cargo door off

Flying the drop zone with cargo door off

|

Target spotted on the side of a hill

Target spotted on the side of a hill

|

Verifying the code

Verifying the code

|

Low-level drops

Low-level drops

|

Right on

Right on

|

Pulling up...

Pulling up...

|

...and away

...and away

|

All done

All done

|

Headed home

Headed home

|

A PRIVATE WAR

Most times going in we went up the valleys fairly low.

Sometimes two planes would start out together but later split to service to different targets.

One time another plane came in below and behind us without our being aware, until he brought his wing up under ours

and almost flipped us over.

Since we had been warned not to use our radios, bad language had to wait until we had both landed.

Another interesting game we played on occasion on our way home empty was to get right down on the water.

Small sail boats on monsoon swollen rivers were sometimes targets of our low flying C-47, trying to blow them over with the blast from the propellers.

Small sail boats on monsoon swollen rivers were sometimes targets of our low flying C-47, trying to blow them over with the blast from the propellers.

|

Away from the hills and mountains, the land was not much above sea level, and during the monsoon season the rivers

spread out for many miles.

The natives lived on small islands with a small grouping of palm trees and traveled from one village to another on

small sail boats.

With our juvenile makeup always just under the surface, we just couldn’t let such opportunities slip by, and so we tried to blow the boats over with our propeller blast. One other time, fooling around like that could have been a real disaster. Our full crew was made up of the two pilots, a radio man, and a crew chief, but on a drop mission they usually stayed behind, the flight time being relatively short. This time the crew chief wanted to come along, and on the return trip (low and over the water), he asked if I could get really down over one of the islands as he said he wanted to study the natives. I did as he asked but waited just a second too long to pull up. These planes do not respond like a fighter, so I took the top off a palm tree, jamming leaves in the oil cooler of the one engine and forcing us to shut it down. The damage on the underside of the fuselage also tore off all of the radio antennas. There we were at an altitude of fifty feet on one engine and looking for a place to land. We were fortunate, and we found a dry field not too far away. We landed, removed a ton of palm leaves from the oil cooler, and took back off. It was a little touchy coming up with a feasible story to satisfy the inquiry of the CO as to what happened to all the under-slung antennas.

As time went on, life at the camp developed a routine.

Some young boys from the nearby village came over to help the new occupants, for which we were all thankful.

They spoke some English, cleaned the basha, gave advice on local problems, and took our dirty clothes home for their

mothers to wash by beating them with rocks in the river.

Boys from a nearby village cleaned the basha and brought our clothes home for their mothers to wash in the river.

Boys from a nearby village cleaned the basha and brought our clothes home for their mothers to wash in the river.

|

We paid them with Hindu money sometimes, but what they would rather have was empty beer bottles (scarce here) and

cigarettes.

There were many monkeys in the surrounding trees, and so they showed us how to catch them by tying a jar to a tree and putting a nut in it. Once the monkey put his hand on that nut, he was stuck, for he could not get his hand out with the nut in it. A light rope around his neck, and you have a pet. Our basha had to go one better. We adopted a small dog (terrier) who had been running wild and was a bit vicious at first, but after feeding her really well for a few days, we became friends. We also had a very young tiger cub that had to be fed milk with a makeshift bottle. American boys do seem to have to have pets. We flew a really busy schedule, sometimes two drops in one day, but as the British army’s offensive successfully pushed the Japanese out of India and deeper into Burma, the distance to the drop zones increased, and we had time for only one mission. With the end of summer, the wet monsoon faded, and life became more bearable. Other Combat Cargo units had been put together and trained and sent in to help us. Too much time with little to do. With an average age of twenty-three, this is a dangerous situation, so things began to happen.

BOYS WILL BE BOYS

First of all, someone found a British motor pool not too far away, and since we were connected, they

permitted us to take whatever vehicles we wanted, which in this case, was one cylinder military motor cycles.

It started slowly, but before long, every plane crew had their own bike, which they proceeded to paint in various

colors like a flying circus. On trips to other fields, we loaded the bike on board and had our own transportation to wherever we wanted to go on the ground.

However, we were warned to be careful when in a town, to always travel as pairs, and to wear the flying

jacket with the stars and stripes on our back.

Before long, every flying crew had their own motorcycle, provided by a British motor pool.

Before long, every flying crew had their own motorcycle, provided by a British motor pool.

|

Some groups hated the British and there had been local conflicts. Of course, there were other things we could do with those bikes, such as racing on narrow dirt roads. We also cleared some jungle growth away and built a hill-climb. This was good fun in the beginning. Problems started when we discovered that the British army was furnished a monthly ration of American whiskey, whereas we were given only a beer ration. Brits love beer and ale, so a trade was made. The end result of this was two racing bikes crashing into and killing a sacred cow and hospitalizing two pilots. The hill climb was also in trouble the day that a happy pilot had his bike near the top roll back on him and catch fire.

We were allowed to keep the bikes but only as necessary transportation, but we found other entertainment. Since we had acquired a dog, the rats still came inside but ran only on the shelves and not on the floor. Our local basha boy said he could make a trap and catch them, and he did. It was a wooden box affair with a sliding door, and it did the job. In the morning, I would dump the rat from the box into a bucket of water and hold him under with a forked stick until almost drowned. Then I would allow him to climb out, at which point the dog would grab then him by the throat and shake him to death. This became a big event each morning that we weren’t in the air, until once I let the rat out of the bucket too soon. He gripped the dog by his nose and from there on the dog lost all interest in future games.

Another diversion was going hunting in the jungle. All that earlier training with carbines and pistols seemed to be going to waste in our branch of the military. We just felt like we had to shoot something and shooting at cans did not satisfy, so in an immature way – carrying only our 45 pistols in their holsters – another kid and I followed the creek into the jungle. The creek was the only way in without a long, hard fight through the heavy growth with a machete, but we hadn’t gone very far along the creek bed when our lower legs and ankles began to really itch. Pulling up our pants, we found that many leeches had been brushed off the heavy undergrowth and found a home on us with good food. Fortunately, we were smokers, and the hot end of a cigarette was enough to cause them to let go and drop. The creek bed was perhaps only about twenty feet wide and had many bends. As we came around a curve, a big black furry animal ran from one side to the other. Our pistols, of course, were not in our hands, so we decided to backtrack about ten yards, wait for five minutes and come back to this spot, this time with our pistols drawn. Again the animal started across the creek, but we both fired and he didn’t make it. Before he went down, he stopped in the middle of the creek, turned and looked at me with a wide-open mouth and growled with an unbelievable set of huge teeth. That had to be the biggest wolf in the world and served to convince us that hunting in a jungle with only a pistol is not a good idea.

We had been told by the natives of the great variety of wild life around us, tigers, elephants, boars, pythons, and the like, some of which we had seen but in some cases, ignored. One particularly hot day, some of the guys decided to ride down to the river on their bikes for a swim. I was working that day, but they told me later that there was a herd of elephants nearby the place where they went in. Not being content to just enjoy the water, someone threw a rock, the bull elephant turned toward them and trumpeted, and many naked men on motorcycles raced for home. On occasion, the wild life didn’t ignore us, either. Our little dog, being a female, came in heat one day. We were awakened that night by much howling and scratching at our door. Not at all sure what was out there, we laid down a plan to remove the problem. One would hold the flashlight, one would open the door, and one would fire the burp (machine) gun. On examination, we found they were a bunch of jackals, but our approach to the problem caused others across the way to be so upset that they threatened to take away our guns.

But besides all this fun stuff, the war was progressing, and we were doing many things with the planes besides dropping supplies. The Japanese forces, which had occupied Burma and closed down the Burma Road in the north as a move to isolate China, were now retreating south. Until 1945, the only American presence was the Tenth Air Force, when Merrill’s Marauders (Galahad force) were put together and sent in to satisfy a directive from President Roosevelt. Earlier, but after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt took the liberty of making Chiang Kai Shek the Commander of the Allied China theatre and gave him General Joe Stillwell as his Chief of Staff. Stillwell took over the training of an obsolete Chinese army which, together with the British, attempted to push the Japanese out of Burma. The Marauders were the key to the success of all their efforts, but only at an extremely high cost and they finally had to be relieved. Another group known as the Mars Task Force came in the latter part of August. We hauled them and their mules to the frontal air strips. They, too, would require scheduled supply drops. In between doing this sort of thing, we had chances to relax.

REAL AIR MAIL

Once in awhile we got to do the mail run. In this area, all mail is air mail, so we would go to a central mail station, pick up the mail in heavy leather bags, and deliver it as needed. If a landing strip was available, we landed; if not, we flew very low and very slow and tossed the bag almost into the tent’s front door. Pickup from these stations required snatching the bag from a pole line with a hook and line from the plane. Sometimes we had our turn of going back to a civilized world for supplies and were told to take a few days off. We truly did enjoy Calcutta, some parts of which were very much British, staying in a world famous hotel (the Grande Hotel), wearing dress uniforms, eating at the best restaurants each with our own waiter, and going to a movie theater to see an American movie starring Rita Hayworth. The really down part of this trip was walking through the busy streets jammed with people who were desperate for food. One young mother came up to me and offered her baby to me for ten rupees. Since we were tightly surrounded by people, we could do nothing for her. I will never forget that experience nor the sight of sick, starving people lying in doorways.

December in Assam was cool and damp, so damp in fact in a tropical jungle, that we experienced a coldness so severe that we had to put on every thing we could find before we could sleep. Military protocol was pretty much forgotten to the point where everyone stopped shaving. A competition began as to who could create the most fantastic beard and moustache. Beards, of course, would cause a problem if it were necessary to use our oxygen masks at high altitudes, but posed no concern with jungle flying. This month, too, did see a great increase in the drive to retake Burma, which definitely affected my squadron. I was in the air a total of nineteen days.

Now it’s important at this time to understand the makeup of the groups that comprised aerial transport. Perhaps best known is that group known as the Hump flyers. Their daily flights across the highest mountains in the world in the worst weather in the world have been well documented. Their losses in planes and air crews exceeded those lost in Europe (850 aircrews). This group’s, known as the Air Transport Command (ATC), main job was to transport materials, but they also transported people when necessary, sometimes using many different types of aircraft. A second large group flying transport planes was called the Troop Carrier, who specialized in moving people, both paratroops and airborne. They also did air supply with para-drops and are best known for the many missions they flew in Europe and especially in the Normandy invasion. Combat Cargo was put together primarily to air-supply the British ground troops in the Burma jungle who were fighting to keep the Japanese out of India, but as time when on, they thought of other things we could do using our specialty skills. Up to this point, most of the pressure on the Japanese had come from the west (India), but it was decided to press them also from the east (China). Stillwell had trained a great number of Chinese who were quartered in the provincial capitol, Chunking. ATC was given the job of moving them to the fighting front at Bhamo, Burma, but from what we heard, their first day was a disaster as the Jap Zeros caught them going in to land. As a result of that, ATC was pulled out and ten planes of Combat Cargo were sent on a fifteen- day detached service to China to replace them.

|

WELCOME TO THE HIMALAYAS

Our new base was at an airfield in Yunnani, along the Chinese end of the Burma Road. That was my first experience of the Himalayans flying the Hump. I was deeply impressed and also very cold. We were a bit further north than when we started and with a four-degree drop in temperature per each one thousand feet of altitude, it was freezing out there. We were dressed for the tropics, and the heating system in the plane was not all it should have been. Also it should be noted that our plane was a C-47A with no engine super-chargers for high-altitude flying. We should have been flying a B model for this kind of work, since eighteen thousand feet was our limit and the higher mountains went well over twenty thousand, and the air pressure and available oxygen in the air at that point are much less than fifty percent of those at normal heights. But you just do what you have to do, so we carefully threaded our way through and landed in our new – but temporary – home in China. This base was defined as one of the fields accepting deliveries from the Hump flights and later on from the reopened Burma Road. Other transport squadrons were commissioned to load up and take all these necessities to forward bases.

Our mission was to fly to Chunking (the provincial capitol), load up with Chinese soldiers, and deliver them to the fighting front in Bhamo, Burma. Of course, no trip is ever made empty, so the plane was loaded with large steel drums of gasoline for the fighters and bombers based there. Our flight to Chunking took a good bit of our own gas, but they were selfish and unwilling to give us any of that which we gave them. Instead, they overloaded us with fifty Chinese soldiers, who, fortunately, were not very well equipped with guns and other supplies so didn’t weigh much. I was really shocked by the poor condition of these Chinese soldiers. They were not at all what we expected of American trained troops. We had to climb rather high and the coldness filled the plane. We had some heat up front, but they had none in the back. Consequently, the body lice left them and crawled all over our controls. The next day we all shaved.

Before we began this mission, the ten crews of Combat Cargo got together and decided how to do this job without the problems that hurt ATC. We knew that the long flight in would be over mountains requiring at least fifteen thousand feet, but after clearing the last range and onto the plateau, we would drop to our usual treetop altitude going into the field. Once on the ground, we would open the door and, while still rolling, begin to unload our passengers, and as the last soldier got out, we would turn and take off. In the typical American way, this thing became a competitive game to see who would spend the least time on the ground. A little hard on the Chinese, but we didn’t lose a plane to enemy fighters, and we moved the ten-thousand-man army into the war zone in twenty flying days.

Now just so you won’t make the mistake of thinking that this mission was all fun and games, I would like to describe a few happenings that weren’t very pretty. First and foremost, you must understand that the weather over these mountains is rated as the worst in the world. The warm, wet air from the Indian Ocean moving north into these very high mountains creates thunderstorms of unbelievable violence, stretching in length for hundreds of miles. With the limitations set on gas and the inability of this airplane to fly above this weather, flying around these thunderheads was not an option, so going from point A to point B had to be a straight line through the storm front. Knowing that the leading edge of a storm will drive you down, it is necessary to go in as high as possible to prevent being smashed into the top of a hill. However, holding absolutely to a set compass heading, this downward force suddenly ends and is replaced by such a strong upward flow that with the plane pointed down and with the engines pulling full power, we gained as much as five thousand feet in a few minutes. It took both of us using all our strength to work the controls to keep the plane from rolling over. One of the other crews did just that, plus had all their front glass broken by large hail stones, but they survived.

Fortunately, storms did not occur often in the colder weather, but heavy overcasts were more common, and since the maps we had were piecemeal, giving us only bare essentials like the location of air fields, finding our way was sometimes quite difficult and one day almost proved fatal. That morning we made our run with the gasoline barrels to Chunking without much difficulty, but coming back with our load of troops on board, we found a solid layer of clouds in all directions. Now in China there were no radio devices to bring us in to landing fields, most of which were located in small valleys surrounded by mountains, so when clouds settle down over a field, that field is closed. This day our delivery of the Chinese soldiers to the fighting front came to a stop, as we heard the voice from the field tower tell the plane ahead of us that the field was socked in and landing was not possible. We were then told to divert to another field not too far away, but as we approached them, I radioed that tower for landing instructions, and received that same reply, ‘socked in.’ Remember, the Chunking deal was no gas from them for our return trip, so that didn’t allow much time to circle around and wait for the clouds to blow away. We were now down to 50 gallons and choked back as much as safely possible, and even that allowed for only 25 minutes of flying time. At this time we were on top of the overcast at thirteen thousand feet and could see the peaks of many mountains sticking up through. After much conversation, we knew that running out of gas sitting up here would eliminate all choices to land thereafter, so in a desperate move, we chose an area where we thought maybe the clouds didn’t have hard centers. Henry, flying on instruments through the clouds, would put the plane in a very tight spiral while descending at a very slow rate, and I would put my face against the glass trying to see anything at all. And indeed I did, as I saw the upraised wing brush against tree tops on the side of the hill which caused me to pull back instantly on the stick to get us back on top again. It would seem that was a stupid solution, but at the time, we had few options.

Now what? Last option – fly for our home base and spiral down over the field. To locate and hone in on any field requires receiving a radio contact which would activate our radio compass, telling us the direction of the radio station (in this case, the landing tower at the field). The contact with the tower was good, but there was such a disturbance that the compass fluttered and spun, giving us little direction at all. We had been warned of misdirections brought on by the placement by the Japanese of radio devices on the hillsides. A quick-thinking control operator told me to change frequency, and he would talk to us from a radio in a plane on the ground. He would home on our signal, and we would home on his. They worked together perfectly and brought us right over the field, which lay under a blanket of clouds. Then a most amazing thing happened: we saw a circular hole in the overcast exactly over the landing strip. Henry cut the engines back to idle and dove through the hole and onto the ground. We knew every second was critical and once parked, I had the crew chief drain the tanks. All that was left was two gallons: one minute of flying time. Those soldiers in the back certainly were put through a most difficult plane ride, sitting four across on a cold floor in an unheated cabin with no seat belts nor handles to give them support as the plane bounced up and down, trying to find a safe home. Even so, I’m sure they were not aware of how close they were to dying.

Not all troop transfers were that fortunate. One of our planes unable to bring his troops in the battle area because of the weather was lucky enough to get into an alternate field. Expecting the situation to be ongoing, the crew shut everything down under the impression that they would spend the night there; this would include putting slide locks on all movable control surfaces. Sometime later, the local weather people had word that the clouds had lifted over the designated landing area, and so informed the crew. Not wanting to overnight in this place, the crew hurriedly loaded up the plane and began their takeoff run. In their haste, however, they had forgotten to remove the locks that made the elevators unusable, so the plane, now at flying speed, could not leave the ground. The plane ran off the end of the runway into a deep ditch and broke in the middle. All but one of the soldiers went into the ditch, filled with gasoline from the broken wings. It then ignited. The speed of the plane was evidently sufficient to carry the nose and cockpit across the ditch, for the crew was not badly injured, but forty-nine Chinese died that day. The pilot was not able to raise his arms for a long time after the accident so was sent home. With this kind of pressure to meet schedules regardless of weather, it was amazing that more weren’t lost.

My crew chief, however, did get lost, if only for a week. It wasn’t always necessary to have him on board on these daily flights, so when we returned at the end of the day, he was gone. A week later, a searching party found him in what was known then as an opium den. After a time, he fully recovered. A few other men began to show the strain and began to come apart. They were sent home. Others, when scheduled for a six o’clock take off, would stay drinking in the officers’ club till the wee hours in the morning and would just not wake up to fly when called. As a result, management closed down the club. We flew through the latter part of December including Christmas day, which is a story in itself. At our age, Christmas Eve in China can get to you and drive you to drink. Good American liquor not being available (except for mission handouts), we talked the medics into giving us medical alcohol, mixed it with grapefruit juice and had a party. The festivities ended abruptly when a few Jap bombers came over around midnight, forcing us to put on our hard hats and heavy parkas and stagger out in the cold to the slit trench, where I proceeded to get sick and throw up, making quite a mess. Shameful. However, at six o’clock the next morning I was sitting in the plane breathing pure oxygen and taking off into the wild black yonder and celebrating Christmas Day in Bhamo, Burma. All this routine ended around the beginning of the new year, and we went back once more to jungle flying.

RETURN TO BURMA

The British Army, with the help of the Mars Task Force in the west and the Chinese pushing from the east, had forced the Japanese to pull back toward Mandalay in central Burma. They were in bad shape, with no fresh supplies of ammunition, food, or medicines, whereas our people were supplied daily by air. They had depended on a single railroad though the jungle, over many bridges which were constantly bombed by the Tenth Air Force out of India. The conditions were right to mount a final offensive to free Burma which, of course, keyed on retaking the Mandalay area, now a Japanese fortress. We dropped paratroops, towed gliders, and still dropped supplies as needed. There were times, too, that we brought wounded back to better medical facilities.

Evacuating wounded to Base Hospital

Evacuating wounded to Base Hospital

|

Stretcher being loaded.

Stretcher being loaded.

|

Preparing for a glider tow into Mandalay

Preparing for a glider tow into Mandalay

|

Loading Indian Paratroops

Loading Indian Paratroops

|

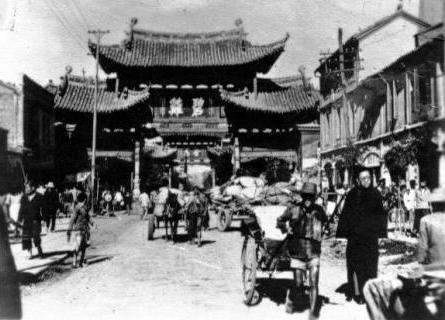

Fourteenth Air Force base landing strip at Chengtu, China.

Fourteenth Air Force base landing strip at Chengtu, China.

|

BACK TO CHINA

By March, the battle for Burma was about over, and we were transferred to the Fourteenth Air Force in China to a base at Chengtu, the most western airfield of any size. Management also added a navigator to our crew, since our expected flights would be considerably longer. The change in living conditions and climate was great. This move took us toward the north and placed us at an elevation of six thousand feet and only about a half-hour of flying time east of the high mountains, in cool, dry air. Chengtu was a major air base, housing a fighter squadron, a bomber squadron, a P-38 recon outfit, and the first operational B-29 Group. The size of this base and others in the area were the direct result of orders from Washington.

BUILDING AN AIR BASE, CHINESE STYLE

Water pump...

Water pump...

|

...four-manpower

...four-manpower

|

Leveling and draining

Leveling and draining

|

Soon to be a new runway for China-based B-29's

Soon to be a new runway for China-based B-29's

|

A large number of laborers made up for lack of mechanized equipment

A large number of laborers made up for lack of mechanized equipment

|

Primarily, the orders were given on the basis of using a large number of the new and extremely large

B-29s to bomb Japan. China, however, had very little in the way of mechanized equipment, so the construction of

runways and other necessities for the daily sorties expected from these bombers was only accomplished with an

unbelievably large number of laborers. In the end, it was a wasted effort, as the result of really poor planning.

The terrain and great distance to the targets, plus the constantly bad flying conditions and inherent weaknesses in the

first generation of these planes, resulted in their being transferred to the Pacific islands.

We were happy to have a photo recon outfit on the field.

Many of us had cameras but nowhere nearby was there a drug store to develop our films.

AMERICAN INGENUITY

Now part of my college scientific training included a pretty intense course in photography.

All I needed to perform came with the presence of an army photo lab with generous technicians.

We built a photo shop and many brought their film to be developed. Most were great photos like these.

We built a photo shop and many brought their film to be developed. Most were great photos like these.

|

From them came the papers and chemicals. With another guy helping me, we cut and shaped aluminum from wrecked

airplanes and built a working photo shop with our own supply of electric power.

Many brought their films to be developed and printed.

Most were great photos, which we put together in book form and sold.

We lived in wooden houses heated with small charcoal stoves and had our meals in a standard army mess. What had not changed was the lack of electricity and running water. Showers were taken in a partially enclosed outdoor wooden cage with the water running out of a raised bucket containing a shower head. The water, of course, had to be first heated in a metal bucket over an outdoor charcoal fire, then dumped into the shower bucket. This was not a bad deal except when it was snowing, but who’s complaining? The outdoor latrine was an improvement, too, as we went from a four-seat job to one having ten, never having to wait one’s turn. This, too, was a good deal for the local farmers, who cleaned out our droppings periodically, mixed them with water, and poured the liquid over their plants. We quickly learned to boil all local vegetables.

Since this base was at the western edge of China, the bulk of our flights were to the advance bomber and fighter bases

in central China. A large amount of war material was delivered to our base, and we then made frequent flights taking

gas, bombs, and bullets eastward – in some cases, a considerable distance over mountainous terrain.

The daily flights affected each of us in different ways. Occasionally, I found the chance to wander into town and learn something about China, taking pictures, eating in small cafés, and going to Mass in a Chinese church. An unbelievable difference between China then and the China that we see today.

|

|

Some guys certainly wanted a break from this schedule and we had a flight surgeon who loved to help out. In this case, Captain Jack, who was bored with little to do, made it known that before the war he had become quite skilled in performing circumcisions and would be happy to use his expertise on any pilot who wanted a short reprieve from his schedule. More than a few opted for this torture. Since this was spring, the weather was mostly cool and dry on the ground, but I remember flying into a hard snowstorm that packed over six inches of snow onto the leading surfaces of the plane, which took several hours on the ground to melt off. The flying characteristics of this airplane changed considerably as the snow changed the shape of the wing as well as adding a weight overload; it dropped like a rock. As was always the case, the biggest problems were weather (plus ignorance of information), lots of mountains, and few landing strips (lack of good maps made it worse). In addition, the plane was piling up hours with little time for scheduled inspections or parts replacement, if available. We did our own maintenance when time permitted.

One day the left engine began to backfire so badly that we had to shut it down and find a level place to land. We began to strip that engine until we found the faulty valve. We then took turns grinding the burned area with mud and crushed rock. The inborn stretchers in the plane furnished sleeping quarters that night. Another time, we ran into trouble with the hydraulic system. The landing gear didn’t want to come down, we presumed because of a leak. We made it workable by replacing the lost fluid with the body fluids of all four men.

EVERYONE’S GOAL - ROTATION

By March, Henry, my flying partner, had enough of this fun and games; he added up his points and rotated home. I was promoted to First Lieutenant and given control of the plane as first pilot. My co-pilots varied between inexperienced and ‘never flew in this plane before.’ Some had only a short hitch in Europe so were sent to China to complete their time. They weren’t a happy bunch and some even broke down and cried after seeing their new home. It took awhile before we became a new and efficient team, but we sure spent a lot of time in the air learning.

We all worked on "CARGO MARGO"

We all worked on "CARGO MARGO"

|

The war in Europe was coming to an end, and many of the occupied islands in the Pacific had been taken back. However, until island air bases closer to Japan were under our control, bombing from China was important, and all flights by us were made during early Spring to build up the supplies for the coming final offensive. The weather was quite often fully overcast, so I chose to fly below the clouds when possible. I well remembered the difficulties we had experienced earlier, flying above the clouds trying to find a break in the overcast. Flying the valleys had its moments of choking, too. The valleys never ran in nice, straight lines, and sometimes turned abruptly at a right angle. One time as we turned such a corner we faced a dead end and were flying right in to the side of a mountain. It was amazing how quickly that plane could be tuned around. Another scare came when we had to fly at sixteen thousand feet above the solid cloud layer, and I noticed that I was becoming light-headed. We had had no indications before then that our oxygen tanks were running empty, and at that moment there did not appear to be a break in the clouds to allow us to descend to a lower altitude. I told the radio man and the co-pilot to shut off their oxygen and sit very still while I would use the last available oxygen looking for a place to descend below ten thousand feet. Fortunately, I did finally find a hole and dropped down safely, but before that happened, the co-pilot almost went completely out of control as on a cheap drunk: raving, swinging his arms, and threatening to take over flying the plane. For a time, things got pretty exciting.

Occasionally, we got away from our daily routine and into something more interesting. The OSS (later CIA) was active in surprising ways. One night, we were chosen to fly a spy disguised as an old Chinese woman into occupied territory. He had to parachute out, of course, and the following night, we had to go back in and drop his supplies, guided by a radio beacon he had with him. Another time, we flew into enemy air space to pick up a pilot who had been shot down but had made his way to an abandoned air field. Since this was a daylight operation, we were given an escort of three fighter planes. While we went in to land between giant craters on this bombed-out strip, the P-51's detoured to an enemy field about a hundred miles away and made a strafing run. No need to waste precious fuel on a simple escort. Another time, we took a Navy weatherman to a strip near the coast. This one was unescorted. Other than these efforts, the only other excitement was trying to play basketball on an outdoor court on the base at an elevation of six thousand-plus feet. Our lungs trained for low level exercise just wouldn’t permit more than a ten-minute run without collapsing.

MONDAY MORNING QUARTERBACKING

As I mentioned earlier, decisions made by those on top were often bad choices. During the early days of the war with Japan, the consensus with those in charge, including the top British and Chinese leaders, was to train and supply a very large Chinese Army which would retake Burma and then take on the Japanese on the Chinese mainland. This included, of course, building a large American air force flying off the mainland. Two events blew this planning away: first, the Japanese closed the Burma Road which was the main supply route to China, and second, the U.S. Navy had great success in destroying much of the enemies water strength and regained control of many of the islands. Although the largest single group in the Japanese army were still in China, fully engaging them in an all-out ground war was no longer a consideration and the training of a big Chinese Army did not happen. General Chennault, however, still intended to use his 14th air force to its fullest without considering the possibility of his air bases being destroyed by the Japanese Army.

A SECOND JAPANESE INVASION

As good flying weather arrived, so did the enemy ground troops. The Chinese Army fled and left a few of the major cities unprotected, so one of our planes was sent in to bring back the cash from the banks. That night, the pilot who had flown the plane went back to pick up something he had left in the plane, and the Chinese guard outside the plane shot and killed him. It was difficult to keep some of the guys from going out to kill Chinese. Instead, we just absorbed that and had a military funeral the next day.

With very little opposition from the Chinese Army and very little warning, the air bases had to evacuate as quickly as possible. Our squadron was called upon to fly at night to these airfields and take the ground personnel and their equipment to a safer location. As it was going to be a long night, our medics gave us a supply of stay-awake pills. While the base personnel were loading us up, we stayed inside the plane, anxious to get out of there as soon as possible. It was a sickening thing to see the base on fire, especially the huge gasoline storage area that we had struggled for months to build. To make it more interesting, a really bad storm arrived with strong winds from the west. An overloaded plane limited to an airspeed of 150 mph and running into head winds of 70 mph is going to face a fuel shortage problem over the mountains while looking for a friendly landing place. With the Lord’s help we made it, but we later heard that some did not.

He almost made it home

He almost made it home

|

As with the end of every mission, the crew went immediately to the dispensary for the double shot of mission whiskey. That put me into a sleep that lasted twelve hours.