FIRE AFTER BOMBING SWEEPS MAYMYO, STILWELL'S HEADQUARTERS IN BURMA.

FIRE AFTER BOMBING SWEEPS MAYMYO, STILWELL'S HEADQUARTERS IN BURMA.

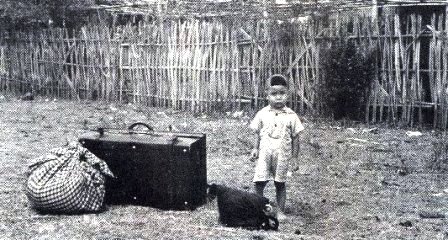

JAP BOMBS AND NATIVE ARSONISTS BURNED OUT MOST OF THE TOWNS AND VILLAGES OF BURMA.

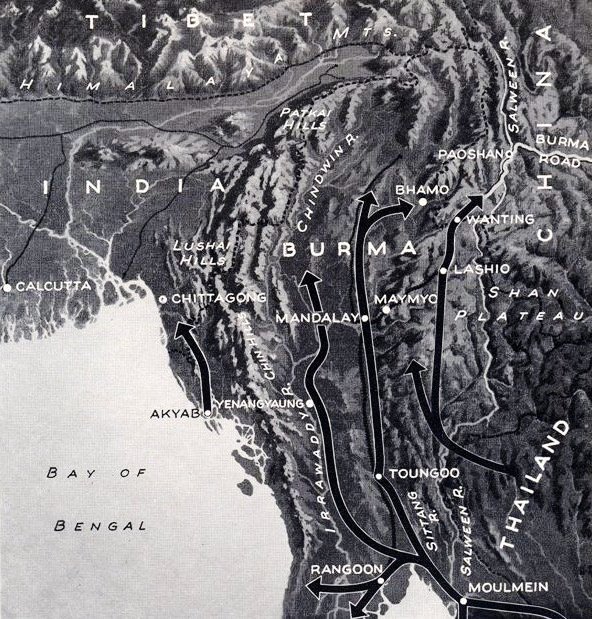

Burma last week became the name of one more lost battlefield for the United Nations. The British had tried to fight it out by themselves, letting in the Chinese armies of Chiang Kai-shek from the north too late to help. With Burma were lost more men, more weapons, more precious resources. Worst of all, there was lost the famous Burma Road by which Allied weapons went overland to China. And the Japs gained a new way into the back door of Free China.

U.S. General Joseph Stilwell's headquarters at Maymyo between Mandalay and Lashio was the brief meeting

place in early April of correspondent Clare Boothe, LIFE photographer George Rodger and Jack Belden, correspondent

for LIFE and Time. Miss Boothe reported on the meeting there between General Stilwell and China's Generalissimo

and Madame Chiang Kai-shek, at which last week's fall of Burma was clearly

foreseen, in her dispatch printed in LIFE,

April 27. She returned last week to the U.S. and is now writing her experiences for LIFE. With her she brought

photographer Rodger's pictures of the Chiang-Stilwell conference and the Jap bombing of Maymyo (above).

Leaving Maymyo in the jeep lent him by General Stilwell, correspondent Belden headed south for the fighting front

around the Yenangyaung oil fields.

Again and again, new Japanese armies appeared out of the "impassable" mountains to the east, on the flanks of the British and Chinese. The simple lines of invasion shown on the map below were at every point a number of weaving tentacles. Hopelessly outnumbered, unrested, unrelieved, without information or water, for three months the United Nations troops fought their way out of a series of traps, always retreating northward. But their every move was reported at once to the Japs by the vast Burmese fifth column. Burmese, who had been described as "pro-Allied" before the invasion, led the Japs through back paths to the Allies' rear. A few loyal Burmese fought well for the British. Others fled into India, carrying a plague of cholera. Those who remained joyfully burned down all the towns that the Japs had not ignited.

Burma was an unexpected battlefield for Chinese-speaking General Stilwell, whom Chiang had put in command of the two Chinese armies in Burma. The landscape of his retreat was endless sand and scrub, from which rose an occasional gold-domed Burmese temple, among arid hills and jagged gullies. Advance headquarters might be in a grove of mango, jackfruit and palm trees, but the Chinese lacked the cover under which they had always fought best against the Japs.

By last week, the main British and Chinese forces were both crossing the mountains on opposite sides of

Burma. Meanwhile at week's end one isolated Chinese detachment, left fighting in the valley, recaptured Maymyo, deep

in the Jap rear, just as Stilwell cut off a Jap column well along the Burma Road into China.

The Chiangs and General Stilwell are wreathed in smiles after April 7 conference at Maymyo, where Generalissimo

Chiang Kai-shek told Chinese generals in Burma that the U.S. Army general was their boss in Burma fighting. Chiang

and Stilwell demanded the offensive spirit and produced it themselves in savage counterattacks on Japs halfway up

the Burma Road.

The Chiangs and General Stilwell are wreathed in smiles after April 7 conference at Maymyo, where Generalissimo

Chiang Kai-shek told Chinese generals in Burma that the U.S. Army general was their boss in Burma fighting. Chiang

and Stilwell demanded the offensive spirit and produced it themselves in savage counterattacks on Japs halfway up

the Burma Road.

LIFE CORRESPONDENT REPORTS ON THE RETREAT FROM OIL FIELDS AMID HEAT, HUNGER, THIRST AND TREACHERY

LIFE CORRESPONDENT REPORTS ON THE RETREAT FROM OIL FIELDS AMID HEAT, HUNGER, THIRST AND TREACHERY

By JACK BELDEN

At dusk on April 16 our jeep pulled up onto the crest of a hill overlooking the Irrawaddy and the oil fields at Yenangyaung. We had come to see the British destroy the last remaining thing of value in the path of the advancing Jap army. Oil tanks and wells were ablaze. But the city power plant had not yet been demolished. Unless it went we knew the scorched earth would be a failure. By the plant we found a few grimy, weary soldiers waiting grimly for the final order. "Wish they'd set a match to this place so we could get the hell out of here ," said one.

Since the power plant had not yet been destroyed we decided the Japanese must still be a good distance away, and we started southward toward Magwe, looking for the front. Soon we ran into columns of Indian soldiers, mixed with guns, donkeys and ambulances, and crying aloud in the dark for water. Dust-caked, tortured faces, drooping mouths, open thick lips, dead-eyed stares revealed in the flickering light of lanterns that these men had been marching all day in terrible heat. Their bandages gleaming in the dark made you know there had been a heavy fight, and even the wounded had to walk.

Soon we discovered the commander lying beneath a tree with his chief of staff and pet cocker spaniel by his side. He told us there had been a terrific fight that morning around Magwe. The Japanese had felt out their

|

Jack Belden is a 34-year-old ex-newspaper reporter who recently joined the staff of LIFE and Time in Chungking. Before that he spent ten years in China where he learned the language and covered the war as a free lance, often getting from one front to another by bicycle. After writing this article Belden returned to headquarters of U.S. General Joseph Stilwell, where he is now. |

We left headquarters, roaring back toward Yenangyaung which was blazing more furiously than ever, lighting the road so headlights were unnecessary. There was a line of cars ahead of us and English soldiers stopped us, warning us that the power plant was about to be exploded. We climbed a nearby hill; suddenly a few yards away we saw a blinding flash, then a terrific explosion split the air, flames burst out in the darkness and soon the great building was an outlined blaze. Sentries gave the go-ahead signal to the waiting cars and we slowly crept up to the

Headquarters at Maymyo of General Stilwell was mission house, set in fragrant garden of roses and poinsettias.

Headquarters at Maymyo of General Stilwell was mission house, set in fragrant garden of roses and poinsettias.

|

The only thing left to destroy was the ice plant and we started toward it thinking of the ice water we would drink before we blew it up, when out of the gloom a man came running with upraised hand, yelling: "Japanese put block across road," and out of the dark came voices uttering those words so terrific in war: "Cut off." The enemy was in our rear.

"The Japs are all around us"

A British soldier jumped onto the car from the bushes saying: "For God's sake, get me out of here, Guvnor,

the Japs are all around us." He had hardly finished those words when the steady clatter of machine guns was heard from

the north, then a duller boom like that of a mortar. That sounded like real strength. The Japanese seemed to be moving

fast for they now had blocks both north and south of us and were only two miles from where we stood. For a few moments

we looked at each other helplessly. Then the commander declared: "The situation is unclear. Nothing we can do now.

Everyone come to my place to sleep. All messages will be relayed to me there and we will find the

true situation in the

daylight." So off we went to the brigadier's quarters.

Jack Belden, LIFE and Time correspondent in Burma, drives a jeep lent him by General Stilwell into Maymyo.

He also carries a tommy gun against rebellious natives.

Jack Belden, LIFE and Time correspondent in Burma, drives a jeep lent him by General Stilwell into Maymyo.

He also carries a tommy gun against rebellious natives.

|

Belden and General Tu at Maymyo. Chinese Generals Tu and Ti in Burma Command were called "Do and Die." Belden

was welcomed at GHQ because he had war news.

Belden and General Tu at Maymyo. Chinese Generals Tu and Ti in Burma Command were called "Do and Die." Belden

was welcomed at GHQ because he had war news.

|

Officers' mess in Maymyo mission house gets delicious strawberries, bad coffee, no liquor. At first bombing

all the Burmese servants ran away.

Officers' mess in Maymyo mission house gets delicious strawberries, bad coffee, no liquor. At first bombing

all the Burmese servants ran away.

|

Stilwell's staff listen to the radio in parlor at GHQ at Maymyo: Stilwell (right)) in dark coat,

bespectacled General Hearn, Colonel Roberts (left).

Stilwell's staff listen to the radio in parlor at GHQ at Maymyo: Stilwell (right)) in dark coat,

bespectacled General Hearn, Colonel Roberts (left).

|

Next morning at 5:30 I heard that the convoy was going to try to break through. Amid the jumble of evacuating cars leaving the vicinity of Yenangyaung and the soldiery advancing from the south, we lost contact with headquarters and wandered up and down searching vainly through wasteland parched by the bitter sun. There was no cover anywhere - merely scrub and brush 2 ft. high on sandy, crumbling earth. Our motor transport couldn't hide but only could be dispersed so that it was an open target for planes from which we constantly ran, each time growing fainter from heat and lack of water.

All through noon and afternoon the only saving factor was that of the planes, though zooming and diving constantly overhead, did not bomb our vicinity, though we heard they bombed Indian troops drawing in closer to us from the south. When at last we found division headquarters we learned that the Chinese had agreed to attack from the north toward the Chang the next morning, but were afraid that we might mistake them for Japanese. I described to officers what the Chinese looked like and offered to go identify them if the occasion arose. A plan, however, was made for the Chinese to seize only the north bank of the Chang and halt there while we drove up to the south bank.

Headquarters itself was in a large temple beneath a great grove of trees which were so green and so protecting that I wanted to cry aloud with the beauty of it. As it grew dark and the coin of Burma's ever blood-red sun sank into the Irrawaddy at our backs, commanders and staff officers gathered in a circle under the trees and held a council of war. Slowly the division commander outlined his plan. The objective of the attack was the small village of Twingon, on the northern edge of a town near the Pin Chang, and was where the Japanese held a road block. All roads converged ultimately at this point and we, with all the motor transport, couldn't get through unless this was captured. "The attack is to jump off at dawn and must be pushed through immediately or our position will be precarious," announced the commander. The officer in charge of supplies then rose and announced that there were no reserves of ammunition and only a small rice ration for one day.

We bedded on the ground, not unrolling our blankets, first filling up the water bottles in order to ensure a swift getaway. At 6:30 in the morning, April 18, we stood on a rise of ground half a mile from Yenangyaung with the commander and watched the first detachment of Scottish soldiers file hurriedly past us into blazing Yenangyaung. As we watched we know our fate depended on them and called: "Give 'em hell, boys!" We received the answer: "We have broken through before - we'll do it again. We're tough!"

About 4 in the afternoon, we were suddenly terrified by screams, as shells began pouring into our exposed position. The Indians came up the mountain. The guns, unlimbered, banged with a terrific clatter, slowly driving back the Jap mortars. We heard the commander was going to make a dash for it, while the chief of staff stayed with the motor transport commander and directed reserves. We asked permission to go. The chief of staff replied, "Certainly. You're noncombatants. It is your duty to get out of this as best you can." We started the mad dash down the hills, around winding curves, weaving in and out of piled-up trucks, radio staff cars and ambulances.

We came out on a small plateau and ran into tanks scooting up and down the road and saw a brigadier come hurtling down the hill in a scout car, rush up to the commander and inform him that the break-through would have to be postponed. We didn't know what happened - only that this was dreadful news and we were not to be given a chance now to escape. But everything was moving in such a swift blur around us that we did not have time to think.

In the twilight, planes swooped over low. They were chased back by our anti-aircraft fire, but we knew, being in such an open position, that they'd be back tomorrow. Tanks began rumbling back from the front, carrying the wounded on their decks and depositing them in the dirt along the road. The commander called roughly, "You war correspondents, make them comfortable." There was noting much we could do but place a sheet on the ground under them, and raise their heads and give them a few drops of available water. I did not hear one groan or complain as they lay, dust-choked on the hillside, with every passing car throwing dirt into their wounds.

By now the terrific realization that we were stuck here for another night, still surrounded, bore in on us with dreadful certainty. Our commander had radioed to the rear, "Position desperate," but the order had come back to hold on and try to get out the animal transport which was some miles to our rear and was also in a trap.

Enemy closes in from three sides

That night, the full seriousness of the situation was apparent even to the humblest private. Our attack on

Yenangyaung had failed and the Japanese had come up the Irrawaddy and landed from gunboats in unknown numbers, forcing

our complete withdrawal from the road junction which we had seized earlier in the morning. From the west, north and

south of us the enemy was closing in, while the situation across the broken ravines to the east was uncertain. We were

without reserves of water, and the small amount left in one truck had to go to the fighting troops and wounded who

couldn't be bathed.

For a third day we were practically without food. Out of this desperate situation a workable plan had to be hammered for tomorrow. Yet this plan was hard to contrive. We were in a position almost checkmate. If we elected to withdraw to the west and south to try to escape across the Irrawaddy, we would find the Japanese in our path and no boats along the river. If we elected again to try to break through Yenangyaung City itself with all our numbers, we ran the risk of being attacked in the flank and, moreover, we would be repeating a plan that had failed once and had already lost the confidence of the men. Finally, if we chose to concentrate all our forces for a direct smash through the oil fields and the village of Twingon, we would run into a Japanese block and be forced to cross the sandy-bottomed waters of the Pin Chang within the range of Jap guns while the Japanese would close in from the south and attack all our transport at our heels. Yet this last alternative was the one the commander chose.

In fact it was the only alternative. Its essence was simplicity. The Chinese would attack from the north at 4 o'clock and we would attack from the south at 6 the next morning - go straight on the road through Twingon village and the Jap block. It was necessary to break through or die - die either of thirst or hunger while slowly being cut to bits by the closing-in enemy.

We pitched beds behind the shelter of the tanks. We saw the fires flickering on the hills to the south of us. And on this weird waterless battlefield in the midst of the oil derricks, with the Japanese growing ever closer, I went to sleep with the thought that if surrender ever came I would make a break for it.

At 6:10 on the morning of April 19, a series of high-pitched screams broke from the darkness of the hills surrounding us. Then came a rapid burst of machine-gun fire, then rifle bullets whistling. The whole camp sprang into action with soldiers yelling: "'Ere they come, the bloody devils, let 'em have it," and our machine-gun fire was soon whipping across the hills, tracer bullets glowing in the early morning dust, whanging their way "Wham! Wham! Wham!" into a derrick straight ahead of us.

As our guns replied we grew calmer. At 7 o'clock tanks swept down the road for attack to try a break-through where Jap mortars and field guns were holding the road under fire. The infantry went after snipers in the derricks. Desperately we hoped they'd break through quickly for by now there was no water to drink and absolutely no food. We lay by the road waiting for news. Three Jap bombers circled overhead, turned and came back low. We were exposed and expected to be decimated and everyone was yelling for ack-ack fire. Suddenly as the planes came straight for us, a terrific burst from the ground shot into the air. White pellets flecked on the edges with fire began curving into the Jap formation. Then the men stood on their feet and started firing rifles and pistols and all of us began cheering and yelling. Wretched and in despair, this ack-ack fire brought us back to life again.

At 9 o'clock the tanks started off in earnest to try a break-through and we raced into line in back of them. The chief of staff, who was staying behind, called: "If you don't make it and have to abandon your jeep, strike out toward the east. You might get through there."

Mortars began to make a wreck of lorries and ambulances - piling up wreckage on the road and closing the block tighter than ever. With a sudden jerk the whole motor column moved forward in the direction of the block with the infantry streaming in and out among the wheels of tank treads and it seemed there was only one thought in everyone's mind: "Hurry, hurry." Gradually, however, quiet was restored and troops began moving off through fields on the right in a wide sweep around the tanks as the whole force was ordered to try a break-through. We could only hope that someone was protecting our rear.

It was now 11 o'clock, the sun was blazing down and the exhausted men began to lie down by the roadside panting and gasping. I had grown so weak that I crawled back to a truck seeking refuge from the sun. Captain Niher sought to find me water but could not. An Indian who was wounded crawled under beside me gasping: "Pani, pani!" but I had not a drop to offer him. Across the hills to the east a pipeline ran and someone shot a hole in it. Water gushed out and the crowd tumbled over each other fighting for a chance to fill their canteens. It seemed as if the morning never would end.

The crossing of the Chang

We constantly heard the Chinese attack was going to start and finally did hear the rattle of fire on

the west and hoped it was really was the Chinese trying to cross the Chang into Yenangyaung. At this moment the

tanks informed us they were abandoning their attempt to break through the main road but would try to find a detour

through ox-cart tracks to the east. Yorkshire and Enniskillen infantry were thrown out on either side. We did not

know exactly where we were going or where the Japs were but we hurried close behind the three tanks, glad at any

chance of crossing the Chang. Behind us were several more tanks but we were the only automobile in the column.

Our way wound across country through thick patches of sand dunes and our driver hastily shifted the jeep into four-wheel

drive but even then we stuck on a high center ridge of the cart road and got out, helplessly planning to give up the

jeep until a tank came and gave us a shove.

As we dipped up and down over the ridges, we caught glimpses of the water of the Chang and somehow we felt if we could reach it we'd be safe. But suddenly the column stopped. The leading tank, which was searching out the trail, radioed it had been mortared. The others wove backward finding a new trail and we went on until we came into a palm tree grove on the banks of the sandy Chang. Animal transport crowded the banks and the Indian soldiers were throwing themselves into the water. We were now on comparatively level ground and roared after the leading tank across the Chang, but when we were on the other side there was no road and we went through a hedge into an open field. Suddenly around us appeared a dozen or so Burmese _ chattering unintelligibly and making motions with their hands. They looked unfriendly and hastily we backed up and returned to the Chang. Now we raced up the bed of the Chang itself behind two or three tanks which were streaking westward toward the main road. On our left from the low ridges of Yenangyaung overlooking the Chang came burst of machine gun fire and we rushed up beside the tank, sheltering ourselves on the far side of the firing.

As we came up the main road we saw green-clad soldiers wearing bits of trees in their caps which were embossed

with a white sun, moving southward across the Chang. A tide of overpowering joy flooded through me as I recognized the

insignia of the Chinese Army and I stood up shouting "Chung Kuo Wan Wan Sui" - which means "China for ten

thousand years." And the Chinese soldiers raised their clenched fists and paused in the midst of smashing through

Jap lines in Yenangyaung and returned their ancient war cry, "Chung Kuo Wan Wan Sui."

|

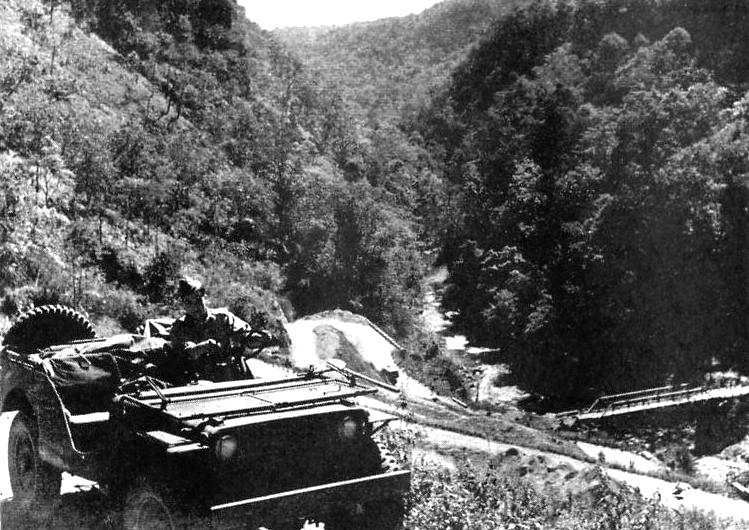

Between Maymyo and Lashio, Japs sliced in from the flanks of the Burma Road through the Shan States in the

southeast. They had reached this little bridge by April 28. This is photographer Rodger's jeep.

Between Maymyo and Lashio, Japs sliced in from the flanks of the Burma Road through the Shan States in the

southeast. They had reached this little bridge by April 28. This is photographer Rodger's jeep.

|

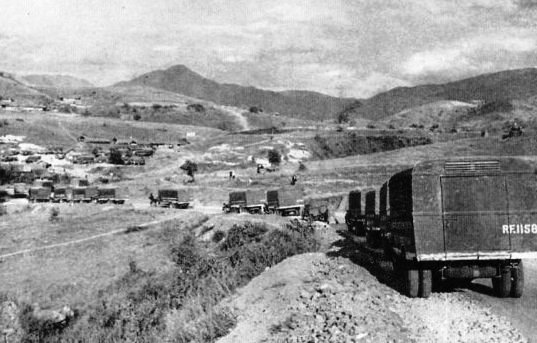

The border between Burma and China was reached by the Japs by May 5. Chinese battled in hills beyond Wanting

(background) while these supply trucks scuttled north with all supplies they could load.

The border between Burma and China was reached by the Japs by May 5. Chinese battled in hills beyond Wanting

(background) while these supply trucks scuttled north with all supplies they could load.

|

Wanting's frontier arch, which Japs captured May 5, shows welcome to Chinese who had passed south month before.

Japs raced on, before the Chinese could destroy bridges, to Salween River (below).

Wanting's frontier arch, which Japs captured May 5, shows welcome to Chinese who had passed south month before.

Japs raced on, before the Chinese could destroy bridges, to Salween River (below).

|

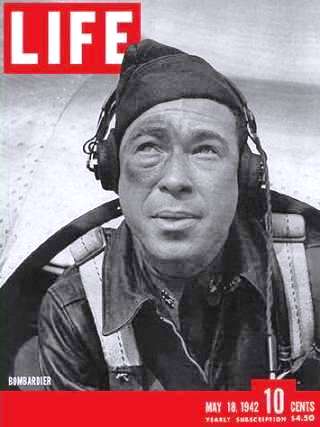

LIFE'S COVER: The man on the cover, Cadet Bombardier Jerome J. Goldstein, 26, seems to be sporting a well-developed

shiner. Fact is that long hours of peering through the soft rubber eye-piece of the famous U.S. bombsight have left

him with a sooty ring around his eye. Goldstein washed out as a pilot, was later called up for training as a bombardier.

Along with hundreds of others at Midland Army Flying School, Midland, Texas, he will graduate as a second lieutenant

in the Army Air Force, one of the 25,000 bombardiers the U.S. needs at once.

Adapted by Carl W. Weidenburner

from the May 18, 1942 issue of LIFE.

Portions copyright 1942 Time, Inc.

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL

HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE

ABOUT THIS PAGE

CLOSE THIS WINDOW

MORE CBI FROM LIFE MAGAZINE