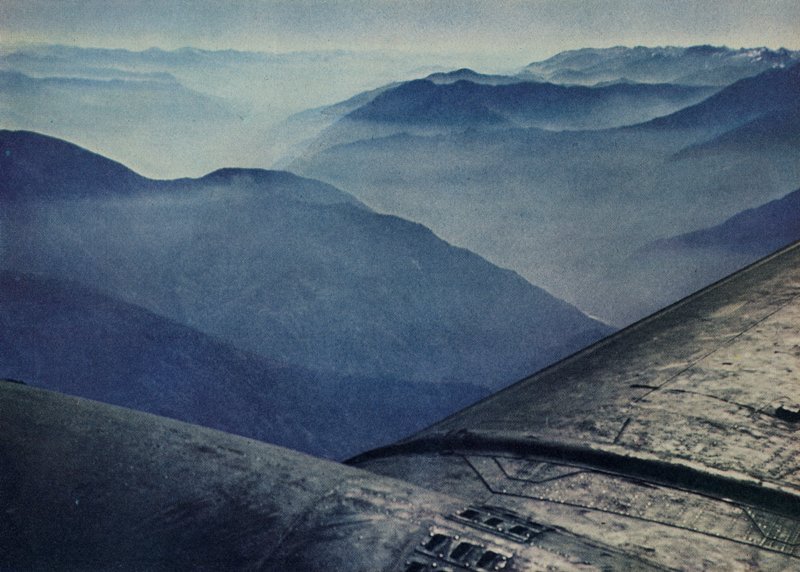

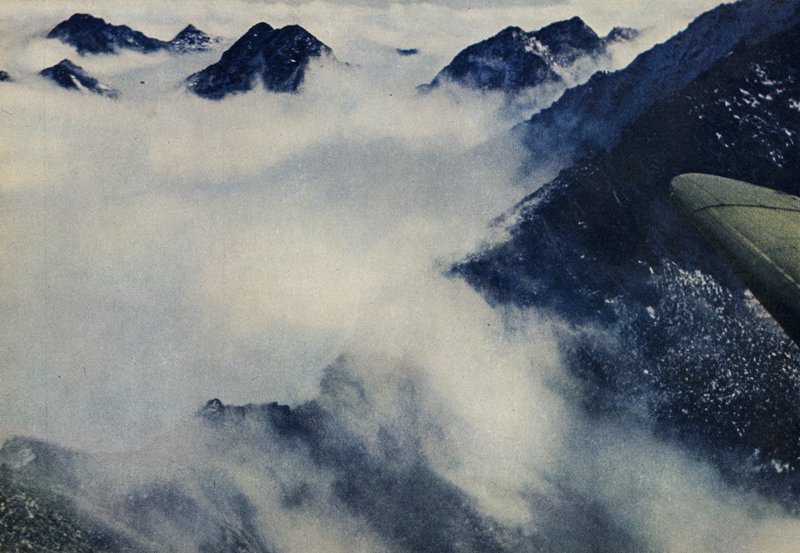

A CHINA-BOUND C-46 STARTS OVER THE STORM SWEPT HIMALAYAN HUMP WHICH BEGINS

IN BURMA EAST OF THE SALWEEN RIVER WITH A CLUSTER OF 18,000-FOOT PEAKS

|

The "Hump" is a line drawn across the eastern Himalayas and the forest of Burma by American blood and courage. It is a sky road 525 miles long that is flown by the Air Transport Command carrying cargo to China from India. Born out of confusion and chaos, it barnstormed its way to maturity and now performs its missions with a streamlined efficiency that has profound ignificance for the postwar world. It has, above all, kept China alive.

The Hump has carried more tons of cargo over a given route than any other aviation operation since the Wright brothers' flight at Kitty Hawk. It flies more planes than any civilian airline the world has yet known and it flies them over the most rugged mountain terrain in the world. It does so with a fraction of any near rival's service facilities. Its operational losses, which are higher than those of any other noncombatant aviation unit in World War II, have exceeded those of many combat units. It flew unarmed during the most dangerous days, through marauding Japanese airpower. It carried the load during every hour of the day and night, halting only when the weather was so bad that "even the birds were grounded."

From bases in Assam, in northeastern India, the planes take off and fly for a few minutes on a course slightly north of east. Rice paddies, tea plantations and jungle thickets slip beneath them, growing denser and denser until they meet in a brilliant green carpet that rolls to the edge of the hills. The hills pucker and crumple up from under the jungle, and then are slashed quickly with white rock scars. The scars grow sharper and soon the hills are mountains, the great terrifying spurs of the Himalayas that reach like knuckled fingers to the south.

When the pilot leaves Assam he has a number of alternate routes, depending on weather, darkness or enemy activity. Should he choose the classic ATC route from upper Assam to the Yunnanese plateau he first crosses Mishmis Hills - little things running between 12,000 and 14,000 feet high. Then he sweeps over the Hukawng valley and the Ledo Road, then over Fort Hertz and the yellow-brown meadows of the upper Irrawaddy. Ahead is the Kaolikung ranger that lifts in spots to 15,000 feet before it drops to the cavernous gorge of the Salween. After the Salween comes the "big hump" itself, the great watershed that separates the Salween from the Mekong. This requires delicate

|

With the Japs now driven from Myitkyina and Allied troops pressing to the south where the mountains are lower, the planes will find better flying. The average monthly tonnage is now incomparably higher than the average carried by truck over the Burma Road which, as a matter of fact, carried a large proportion of civilian and commercial goods of relatively little value. With the present imminent reopening of the land route to China, the Hump will handle relatively lighter, higher-priority cargoes. But streamlined and equipped with a few amenities even carrying lighter loads - the Hump still remains a skyway over hell, a great and long-censored chapter in American history.

The exact origins of the Hump run are lost in the confusion of our entry into the war. The China national Aviation Corp. made a test flight in 1941. Then the Allied collapse in Burma in the spring of 1942 isolated China and suddenly gave the establishment of regular air service between India and China the highest war priority on the Asiatic continent. But not even Brig. General William Donald Old, the first U.S. Army pilot to make the run, remembers whether it was April 9 or 10 in 1942 when he first took his DC-3 over the big hill. He was flying a cargo marked SUPERSECRET and SPECIAL RUSH - it was gasoline to refuel the Doolittle planes in China after they bombed Tokyo.

Pan American stripped 10 cargo carriers from its Africa run, and in them Old and the other early-day ferry pilots tackled the toughest mountain range in the world, kept China in the war, brought supplies to General Stilwell in Burma, evacuated the wounded from the front. They did so without weather reports, navigation aids, adequate fields, ground transportation or radio. They took off on instruments, flew by compass, let down by calculated flying time. Their home field in Assam was crowded with RAF transports and Mohawks, with American planes, Pan American cargo carriers and C.N.A.C. passenger liners. The officers and men ate together in one mud basha with a dirt floor; there were no lights, native cooks served bully beef and British biscuits. The only alarm clock belonged to General Old. He waked each of the men individually at 3:30 in the morning and drove them to the field. There was just one shift - a 16-hour shift - broken only by sandwiches and hot drinks. The Japs were in the air constantly. The only protection the Hump had was two P-40s loaned by Chennault and two P-43s loaned by the Chinese Air Force. In May, 80 tons were flown to China, in June, 106 tons, in July, 85 tons.

Assam base attacked by Japs

General Claire Chennault's China Air Task Force, then a subordinate unit, was setting up an agonized shriek for more material. By autumn 600 tons a month were being flown over the mountains, and an operational pattern was worked out. The Japanese had already begun to realize the importance of the Assam route and in October

The trail-blazing period was over when the Tenth Air Force handed over operations to the ATC in December 1942. Immediately thereafter, for security reasons, a news blackout was slapped on that lasted until early this year.

During 1943, when American flying skill and air transport techniques accomplished legendary miracles, the Hump operations were under Brig. General Edward Harrison Alexander, an able man for a heart breaking job. The men still lived in filth and squalor. Headquarters was a tea bungalow which acquired a name after Colonel Gerry Mason found the staff placidly watching an air raid. He barked affectionately: "Take cover, you dumb bastards!" From then on the official title was Dumbastapur, and it was so marked on maps. There was no time to spare for the niceties of life. Fields had to be built and the proper transport plane had to be found. The early runs had been made in DC-3s, whose normal ceiling was 12,000 feet and which had to be flown at 17,000 and 18,000. The C-87 had trouble with icing, and maintenance of its four engines was a drain on limited repair facilities. Alexander chose as his ship the new Curtiss C-46 - a twin-engined, big-bellied, ugly workship. It was just beginning to come from the assembly lines

in the U.S., but the need for it was so great that it was rushed to Assam before the bugs had been taken out. There was no time for routine test flying to build up a backlog of pilot experience and a knowledge of spare part requirements. The planes came out factory-fresh and were test flown in actual operation under conditions no other plane in aviation history has had to meet. They were subjected to all the climatic conditions of India and the Hump dust, excessive heat, flight with maximum loads at higher than maximum serviceable altitudes, at maximum rates of climb, through turbulent winds and storms. The men flying them were youngsters whose experience in many instances

It was during this period that one of the squadrons wanted to use as its insignia an upraised arm with its clenched fist brandishing a flailing cat-o-nine-tails that bore a simple motto: "Get over the Hump." Another squadron chose as its device a cartoon of an idiot with crossed goo-goo-eyes and an index finger playing with a burbling underlip. Underneath was the motto: "Too much, too soon."

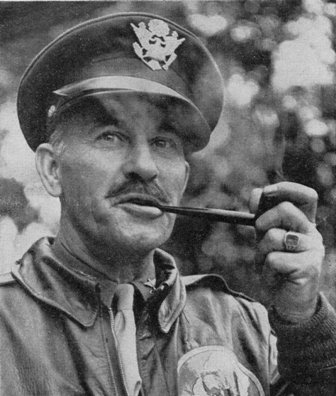

As demands from General Chennault's Hump-supplied air force and from the Chinese grew in insistency, a crack team from the ATC's African operation took over. General Alexander, who had labored for almost a year at a man-killing pace, went home for a rest. Major General Harold L. George, chief of all of ATC's global operations, set up a new headquarters in Delhi and placed. Brig. General Thomas O. Hardin of Forth Worth, Texas in charge of the Hump itself.

Hardin had superb qualifications for a murderous job in which the graph of rising tonnage was almost paralleled by another graph showing the number of American lives lost in getting the goods through. A man with cold blue eyes and a voice that cracked like a whip, Hardin could fly as well as any of his men. He was equally skilled as an executive and practical diplomat. He had been one of the architects of the 1938 legislation which reorganized the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Authority and, as chairman of the Air Safety Board; he laid down the flying principles that have made U.S. civil aviation line the safest in the world.

"We done it again!"

By the start of 1944 tonnage over the Hump had doubled within a year and President Roosevelt directed that the wing be cited for service. When the War Department reported that according to its directives only combat units could receive presidential citations, the President ordered that the directives be changed. Still the demands kept increasing. Chennault's forces were moving their bases farther east as they ranged over the China coast in search of Japanese shipping. The project of using B-29 Superfortresses to bomb the Japanese mainland imposed new

Fighting men, diplomats and jeeps, bombs, trucks, ambulances - anything that can be broken down into four-ton units - have gone over the Hump. Heaters were removed from the planes to save weight and in winter temperatures in the aluminum shells dropped as low as 20° to 40° below zero. Ice can build up so rapidly on the wings that within five minutes a plane loses all flying capacity and drops like a rock into the jungle. In summer there are monsoons - black, solid masses of rain and wind that flick a plane about as if it were a feather. There are convection and thermal currents that send the instruments into crazy spins. The indicated rate of descent may be 1,500 feet a minute going down when the altitude meter shows 1,500 feet going up. A pilot may be putting his plane down as hard as he can and the wind and clouds will be sending it up twice as fast as he is descending; or vice versa, which is worse. In addition there are Jap fighters, fewer now than before but still a threat, for there is no aerial

barricade in the world that can prevent a lone sniper from slipping through.

Escapes and legends

The men love stories about crews who escape from the jungle. There was the time when a plane iced up while carrying Chinese troops who had no parachutes. The pilot decided to crash-land but ordered his radioman and his copilot to bail out. The two men landed in a great tropical tree and wandered for 15 days before friendly natives found them. When they were safe at last they learned that their plane had righted itself somehow and made home base.

Most of the current rescue stories revolve around a great flier, Captain John Porter of Cincinnati, Ohio, a rare and shining individual. he was the first leader of the 11-month-old Search and Rescue Squadron known as "Blackie's Gang." It has its own warehouse and ground personnel run by a former New York nightclub operator named Joe Kramer who handles all rescue gear - food, medicine, bandages, boots, clothes, compasses, maps, signaling panels, playing cards, books, Bibles and goods to barter with natives. As soon as a lost crew is spotted by the rescue squadron, messages are exchanged between ground and air, and the rescue plane drops food and supplies. Thereafter, day by day, the plane hovers over the men on the ground, nursing them along and directing them out of the jungle to safety.

Porter brought his squadron to a high operational pitch but he added his own flair. Once he dived his lumbering DC-3 onto a parked Jap plane and strafed it with a Bren gun, killing the pilot and destroying the plane. On his last mission he went out over the Irrawaddy valley and was jumped by a swarm of Zeros. He radioed back that he was being attacked. The last words heard from him were: "Wait a minute. I can't talk now. I got to take a couple of shots at these . . . "

Casualties among Hump pilots have been high but the strain of keeping the operation going is not limited to air personnel. All men assigned to the Hump, including Service of Supply men responsible for the monumental task of bringing in and dispersing ground stores at the take-off bases, are subject to mental as well as physical hazards. These men are plagued by Assam's summer heat and malarial mosquitoes. Sweat drips down from their chins onto their desks and their reports. Promotions are slowed up by the table of organization laid down in faraway Washington. Post Exchange supplies are even fewer than in China. There are seldom razor blades or soap, books or magazines. There is nothing much to do but sit around in the barracks or play cards.

It has only been natural that under such conditions some men have cracked. When they do they are declared to be "Hump Happy," a phrase loosely used to describe any number of neurasthenic disorders. Sometimes pilots have just operational fatigue from too much flying, too little eating or sleeping. For such cases a furlough or a trip home is prescribed. At other times two or three trips over the Hump crack a pilot's adjustment mechanism. In these cases stern measures are necessary. It is impossible to let a flier off if he quits after one or two flights while other men are being ordered out on the same run day after day. The Hump requires tough men, but it also supplies excellent medical control. Wing Surgeon Colonel Donald D. Flickinger, one of the ablest doctors in the U.S. Army, built up the system. Once he parachuted into head-hunter country to treat injured crew and passengers on the long march out to safety.

Such men as these and scores of others in big and little jobs have kept the Hump going. Yet the spirit of all the men is the most important thing. Some crack but most of them sweat it out, lean, homesick, malarial, tough. They have acquired a certain grace in the face of danger that comes from practice at keeping their heads when trouble shows. Theirs is the old, rugged strength of America's early pioneers and, 12,000 miles from home, their spirit blazes in the deeds they do and the songs they sing. They have one Casey Jones ditty which captures their flavor:

These Hump men fight the Japanese, the jungle, the mountains and the monsoons all day and all night, every day and every night the year round. The only world they know is planes. They never stop hearing them, flying them, patching them, cursing them. Yet they never get tired of watching the planes go out to China.

The red light in the operations tower sweeps the field from end to end. In the darkness the pilot firmly advances the throttles and the manifold pressure creeps up inch by inch to the danger point. Then, with deafening acceleration, the plane comes hurtling down the runway. Two shafts of dazzling white flash beneath the wing panels and stab a path across the black runway. The red and green lights on the wing tips and tail make three brilliant streaks racing parallel across the edge of the night. With infinite gentleness the pilot draws the wheel back to him and the plane is airborne. With a final ear-splitting screech it pounds past the operations tower. Someone in the tower grimaces under the impact of the throbbing motors and mutters, "Hang her on the props, kid,

hang her on the props!" The pilot cuts his wing lights, eases the terrible pressure in the manifold, synchronizes the props - and the plane is alone and on its way, across the Hump to China.

By August it was clear that Burma was going to stay closed for a long time, that China was thoroughly blockaded, and that if she were to be supplied at all it would have to be by air. In that month Major General Clayton Bissell of the Tenth Air Force was placed in command of the operation and its volume began to rise.

came the first raid. A group of officers in Assam was sitting in the mess talking when the sound of a heavy formation was heard. "What's that?" someone asked. A colonel went out in the sun and counted. "Twenty-seven bombers," he reported and then, realizing what he was saying, gasped: "My God - they must be Japs! We haven't got that many bombers." The Japanese blitzed the main runway and warehouse as they came over; then Zeros came down to strafe the grounded planes. "Get out of my way, cobra," a Negro soldier warned as he dived into a foxhole.

AT MAINTENANCE FIELD mechanics repair and replace. They strip good parts from wrecked airplanes to use as replacements.

AT MAINTENANCE FIELD mechanics repair and replace. They strip good parts from wrecked airplanes to use as replacements.

would not qualify them for a copilot's job on an American airline. Critical parts began to give way all at once, at rates which no previous experience could have forecast. Men died in the air and on the ground learning about the ship, ironing out its weaknesses, beating out a body of experience in the presence of overpowering military emergency.

BRIG. GENERAL TOM HARDIN, tyrannical and colorful commander of Hump fliers, raised the freight tonnage by starting over-the-Hump night flights.

BRIG. GENERAL TOM HARDIN, tyrannical and colorful commander of Hump fliers, raised the freight tonnage by starting over-the-Hump night flights.

Driving himself and his men, Hardin lifted tonnage to almost unbelievable levels. He was ably assisted by such men as Lieut. Colonel Edgar Schroeder and others who had helped him replace Pan American with ATC in Africa. Schroeder once said: "I figure if we get enough people mad at us we'll get things done." Things were done. Hardin put the Hump on a night-flying, 24-hours-a-day basis. Accidents and deaths jumped, but the curve of deaths rose less steeply than the curve of tonnage. Flying groups at different fields were set up on a competitive basis. Men watched the daily charts as eagerly as they used to watch baseball scores at home. As day after day saw records smashed, the big blackboard outside headquarters proudly proclaimed: "We done it again!"

burdens. When the Japs drove on Imphal this spring to cut the Hump's land-supply route, British troops guarding the Burma border got into trouble. The Hump was stripped to its ribs meeting these emergencies. Rush supplies were flown to roadless jungle points and new feats of flying skill performed. These new skills paid off when General Frank Merrill's marauders struck at Myitkyina last May and "Uncle Joe" Stilwell demanded thousands of airborne Chinese troops to close the siege. Only one Chinese soldier died during this entire aerial movement. He suffered a heart attack.

ONE NIGHT'S HAUL over Hump filled this China air depot. Freight from Assam included motors, bullets, trucks,

toothpaste.

ONE NIGHT'S HAUL over Hump filled this China air depot. Freight from Assam included motors, bullets, trucks,

toothpaste.

Living like dogs and flying like fiends, the Hump pilots have acquired a style of their own. They have the same sense of superiority over pursuit pilots that a Brooklyn truck driver feels over a liveried chauffeur in Manhattan. "What the hell?" they say. "A pursuit pilot has six .50-cal. guns in front of him and 400 mph in his engine. We fly the same country with a pistol and a tommy gun." They tell stories that are part of the Hump legend - how in the early days some of the boys took off and bombed Hanoi with old fragmentation bombs they fused themselves and pitched out from the DC-3s side doors by hand. One pilot, carrying an Army colonel back from China, swooped low over Lashio's ack-ack at rooftop level and when he gave the signal, "Start pitchin'," the colonel dumped bombs overboard one by one. There was another pilot, lost over the Hump at 20,000 feet and with his gasoline running out,

who called to get a radio bearing. Those on the ground, listening for his test message, heard him faintly repeating a locally popular risqu joke about a sweater girl. The ground station brought him in safely.

TIBETAN CLOTHES worn by Asst. Engineer John Huffman were given him by natives after he was forced to bail out. It took a month on foot to get back.

TIBETAN CLOTHES worn by Asst. Engineer John Huffman were given him by natives after he was forced to bail out. It took a month on foot to get back.

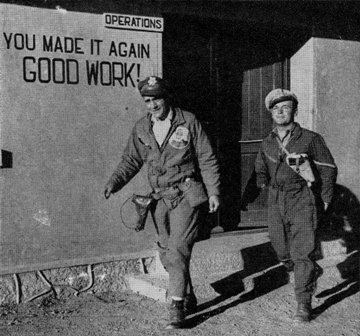

AFTER A SUCCESSFUL FLIGHT, Captain "Bamboo Joe" Barube and Lieut. Ernest Lajoie leave operations office in China. Stopover there is 60 minutes.

AFTER A SUCCESSFUL FLIGHT, Captain "Bamboo Joe" Barube and Lieut. Ernest Lajoie leave operations office in China. Stopover there is 60 minutes.

It was Sunday morning and it looked like rain,

Around the mountain came an aeroplane;

Her carburetor busted and her manifold split,

The copilot gulped and the captain spit.

Cockpit Joe was comin' round the mountain,

Cockpit Joe was goin' to town,

Cockpit Joe was comin' round the mountain

When the starboard engine she done let him down.

MIST HANGS HEAVY on ridges of Himalaya Mountains between great Salween and Mekong River valleys, where a C-46 Hump pilot crosses on way to China terminal.

MIST HANGS HEAVY on ridges of Himalaya Mountains between great Salween and Mekong River valleys, where a C-46 Hump pilot crosses on way to China terminal.

ON A CLOUDLESS DAY the sky bathes the jagged, snowy landscape of Hump route with shades of blue. Note the crystalline appearance of rocks beneath wing of the plane.

ON A CLOUDLESS DAY the sky bathes the jagged, snowy landscape of Hump route with shades of blue. Note the crystalline appearance of rocks beneath wing of the plane.

TOWERING SNOW-TIPPED PEAK, just a few minutes off regular Hump line to China, has striking beauty in sunlight; when cloud-shrouded it is a dreaded obstacle for pilots.

TOWERING SNOW-TIPPED PEAK, just a few minutes off regular Hump line to China, has striking beauty in sunlight; when cloud-shrouded it is a dreaded obstacle for pilots.

WHITE CUMULIFORM CLOUDS settling around rocky 22,000-foot peaks in Tibet keep fliers from using lower mountain passes, are a visible warning of treacherous air currents.

WHITE CUMULIFORM CLOUDS settling around rocky 22,000-foot peaks in Tibet keep fliers from using lower mountain passes, are a visible warning of treacherous air currents.

LIFE'S COVER: Walking along with their hands on their heads are part of the multitude of German prisoners which have been and are still being captured by the Americans in France. Last week General Dwight D. Eisenhower announced that German casualties in northern France now amounted to more than 400,000 men. Of them, 200,000 are prisoners. German equipment, captured or destroyed, otaled 1,300 tanks, 20,000 transports, 1,500 artillery guns, 3,545 planes and 300 warships.

LIFE'S COVER: Walking along with their hands on their heads are part of the multitude of German prisoners which have been and are still being captured by the Americans in France. Last week General Dwight D. Eisenhower announced that German casualties in northern France now amounted to more than 400,000 men. Of them, 200,000 are prisoners. German equipment, captured or destroyed, otaled 1,300 tanks, 20,000 transports, 1,500 artillery guns, 3,545 planes and 300 warships.

Adapted by Carl W. Weidenburner

from the September 11, 1944 issue of LIFE

Portions copyright 1944 Time, Inc.

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE

MORE CBI FROM LIFE MAGAZINE CLOSE THIS WINDOW

Visitors

Since October 15, 2009

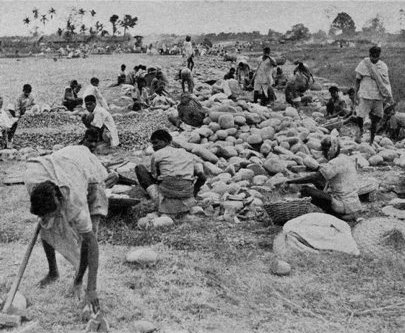

NEW TAXI-STRIP FOUNDATIONS are laid by natives of Assam valley, drafted from rice paddies and tea plantations.

Doubling of the China-India air traffic last year meant day-and-night work on new fields and on installations to

handle increased volume.

NEW TAXI-STRIP FOUNDATIONS are laid by natives of Assam valley, drafted from rice paddies and tea plantations.

Doubling of the China-India air traffic last year meant day-and-night work on new fields and on installations to

handle increased volume.