|

STORY OF THE LEDO LIFELINE

Dedicated to the officers and men who gave their lives that this project be accomplished

Prepared by the Office of Public Relations, USF in IBT, Advance Section, APO 689, in conjunctionwith the Information and Education Division, IBT. This publication has been passed by IBT and CTPress Censors for mailing home.

INTRODUCTION

This booklet has been prepared to give you some worthwhile information about the Stilwell Road.It tells about the places to be seen along the great military supply line, about the customsand religions of the people who inhabit this remote corner of the world, and about the partplayed by the men who pushed through the greatest engineering project ever undertaken in timeof war.

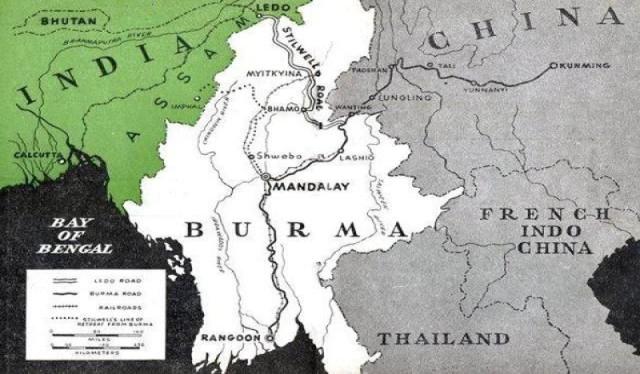

The opening of a land route and pipeline, to maintain a constant flow of supplies to China,has been the Number One job of the India-Burma Theater of Operations. Planned and visioned byGeneral Joseph W. Stilwell, the gigantic project was carried to a speedy completion through thecombined efforts, leadership and ability of Lt. General Dan I. Sultan, Commanding General ofthe India-Burma Theater, Major General W. E. R. Covell, Commanding General, Services Of Supply,IBT, and Major General Lewis A. Pick, Commanding General of the Ledo Road project, with thesuperb teamwork of thousands of American officers and enlisted men, plus the help of soldiersand peoples of our allies.

There isn't a great deal to Ledo and the forward areas. Troops may not display much "spit andpolish", for they have lived under rigorous conditions, toiled and sweated through monsoon mudand blistering heat, fought the Japs, jungle, malaria and monotony. But behind the drab exteriorlies a fantastic story of accomplishment, certain to thrill anyone who traverses the 1079 milesof the Ledo and Burma Roads, the two great highways which form the Stilwell Road.

For the first time in the world's history, India and China have been joined by an overland supplyroute. The ingenuity and efficiency of industrial workers on countless production lines back homeand the blood, sweat and tears of American men in uniform, made this lifeline a reality insteadof the "impossible engineering pipe-dream" the project once was termed.

Every branch of the service played a part in hacking through this great artery. Colored and whitesoldiers, working long hours under soul-trying conditions, have built Stilwell Road. From theInfantrymen whose blood paved the way, to the Air Corps men who flew vital supplies to forward areas; from the Engineers who day and night pushed the point of the road deeper into thewilderness, to the Quartermaster drivers who wheeled big cargo trucks up to the front lines throughmud and rain and dust; from the medics who attended the sick and wounded, to the Signal Corpssoldiers who strung communications across swamps and through jungles - these men and other units,Pipe Line, Foresters, Malaria Control, Ordnance, Special Service, Chemical Warfare, Railroaders,Administrative, all have contributed a vital share to building the road. And, working with thethousands of Americans, have been thousands of Chinese and Indians, all helping to open China'sblockaded borders and to keep a steady flow of supplies rolling to her, for the first time sincethe Japs invaded Burma in 1942.

ROUTE OF THE STILWELL ROAD

Ahead of you are 1079 miles of the roughest driving you'll ever experience. For Stilwell Road isa military highway. The niceties of the modern four-lane thoroughfare of America over which youused to speed on your way to a Sunday picnic in the park or a dinner date with Susie have beensacrificed for military expediencies.

Stilwell Road doesn't by-pass swamps or rough mountain terrain so the drivers of the big trucksladen with supplies can have an easier life. It lunges headlong into the precipitous PatkaiMountains, jungled tailbone of the Himalayas which separates Assam and Burma. It clings precariously to perpendicular mountainsides, leaps across turbulent mountain rivers. And thenit plunges breathlessly down into Burma's vast Hukawng Valley.

Leaving the Patkais Stilwell Road cuts across the swampy Hukawng, straight as the flight of anarrow. It crosses the bloody battleground of Jambu Bum Pass, where men of Merrill's Maraudersand Chinese infantrymen battled the Japs for control of the gateway to the Mogaung Valley, anddrops gradually into the Moguang's marshlands, high with elephant grass.

Beyond Warazup on the Moguang River Stilwell Road skirts low, jungled hills which once were knownonly to big game hunters in search of elephant or tiger. West of Myitkyina, it bridges the broadIrrawaddy River with the longest floating bridge in the world, and cuts sharply southward over rolling hill country to the teak groves of Bhamo.

Bomb-gutted Bhamo, with its shattered pagodas and giant gilded Bhuddas, is the pivot point ofStilwell Road. Here it veers sharply to the east and tops 5000-foot mountains, following the ancientcaravan route used by Marco Polo on his journeys into China centuries ago. For more than a hundredmiles it winds above emerald gorges matted with vegetation, then emerges upon the barren ShweliRiver Valley.

In the Shweli Valley Stilwell Road leaves the jungle behind and threads its way across terrain dottedwith round, naked hills up to Wanting on the China-Burma border.

Out of Wanting Stilwell Road enters the foothills of the Himalayas, passing caves which the Japsblasted into solid rock mountainsides; caves in which Jap soldiers lived, fought and died as theChinese Expeditionary Force battled to clear the enemy from the Burma Road. It scales SungshanMountain where, after three months of vicious warfare on the "Roof of the World," Chinese engineersburrowed beneath Jap fortifications, set off 6000 lbs. of TNT and blew the top off the mountain.

The countryside of China over which Stilwell Road passes has a grandeur seldom equaled. The mountainsare steep and rocky and their tops are fringed with pine trees which stand out against the skylinelike lace on some giant shawl. The narrow mountain valleys are bright mosaics of vari-shaded greens,with splashes of yellow here and there. And everywhere are the ageless rice paddies, crumbling rocktombs and clusters of red mud huts.

Stilwell Road threads through deep gorges, skirts and crosses raging rivers, twists and twines acrossrange after range of mountains and drops suddenly down into valleys in a dervish of hairpin curves.And it leads northward, past Mangshih, Lungling, the Salween Gorge, Paoshan, and then does a columnright to the east past Siakwan, Yunnanyi, Chennan, Lufeng to ancient Kunming.

STILWELL ROAD MILESTONES

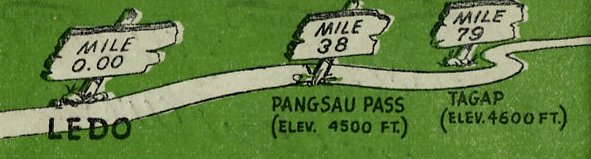

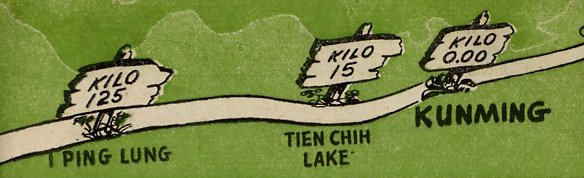

Here are the mile marks of the road which lies ahead of you. Consult them for interesting dataon the country through which you will pass. Figures from Ledo (Mile 0.00) to Wanting (Mile 507)are given in miles. Figures from Wanting (960 Kilometers) to Kunming (0.00 Kilometers) are givenin kilometers.

|

MILE 38 - This is the summit of Pangsau Pass (Elev. 4500 ft.) and the India-Burma border.From the top of the pass, eight miles of steep, winding road stretch in a vast panorama below you.And, as you start down into Burma, the blue waters of Forbidden Lakes glimmer in the swampy valley floor to the south.

MILE 79 - This is Tagap Hill (Elev. 4600 ft.) It marks the farthest point of Jap infiltration innorthern Burma. In March 1943, a large Jap patrol advanced to Tagap (a Kachin village) but was forcedto turn back when their native porters and elephant contractors deserted.

MILE 103 - Shingbwiyang was the site of the Japs' northernmost supply base in Burma. It was capturedby the American-trained Chinese Army in India late in 1943 and was turned into an American sub-depotwhen engineers pushed Stilwell Road down from the Patkai Mountains to the floor of the Hukawng Valley.Shingbwiyang, which once was a large Kachin village connected with the outside world by trails whichwere passable only during the dry season, lies at the foot of the Patkais. It is drenched withcontinuous rains during the monsoon, experiencing seasonal rainfalls exceeding 200 inches.

MILE 178 - This is Jambu Bum (pass) where a fierce week-long battle was waged by American and Chineseinfantry to clear the gateway to the Mogaung River Valley. This was a decisive battle in the Northern Burma Campaign which laid the groundwork for the surprise assault on the Jap citadel of Myitkyinaa few weeks later.

MILE 189 - This sub-depot on the Mogaung River, known as Warazup, was the scene of the biggest tank battlein northern Burma. The narrow streams which you cross in this area during the dry season become angry torrents hundreds of yards wide during the monsoon. The entire valley becomes one vastswamp. In this section the roadbed has been built as high as 15 feet above the floor of the valleyto protect the highway from encroaching floods, prevalent between May and October.

MILE 234 - This is the Kachin village of Namti, onetime Jap communications center midway betweenMyitkyina and Mogaung on the Rangoon-Mandalay-Myitkyina Railway. It now serves as an American sub-depot.

MILE 254 - Here Stilwell Road crosses the Irrawaddy River over the longest bridge of the Ledo lifeline.

MILE 372 - Bhamo once was the third largest city of Burma. Today it is a shambles of demolishedpagodas and burned-out buildings sprawled dead and grotesque among groves of teak trees on theIrrawaddy River.

MILE 439 - Namkham, in the Shweli River Valley, is another of Burma's war-shattered towns. It isthe location of the great Temple of the Golden Eye, now in ruins, and Dr. Gordon S. Seagrave'sfamed Burma hospital. It was from Namkham that Dr. Seagrave and his petite Burmese nurses begantheir retreat from Burma in 1942 - an exodus described in Dr. Seagrave's book "Burma Surgeon."Dr. Seagrave - now a Lt. Colonel in the U.S. Army Medical Corps - and his nurses recently returnedto Namkham after having marched with American and Chinese troops from Ledo through north Burmain the jungle campaign to drive the Japs from the path of the Ledo lifeline to China. Dr. Seagrave'shospital, situated on a knoll overlooking the town, served as a Jap army headquarters and was demolished by American bombers and Chinese artillery. Today, however, the hospital is being restoredand wards have been set up among its ruins. In the meantime, part of Seagrave's medical unit moved on south in Burma with the front line troops.

MILE 465 - Mongyu is a tiny Shan village on a hill overlooking the junction of the Ledo and BurmaRoads.

MILE 507 - Wanting (969 kilometers from Kunming) is a handful of customs buildings scattered amongbarren hills on the China-Burma border. Wanting was the scene of some of the bloodiest fightingof the Salween campaign, changing hands three times before soldiers of the Chinese ExpeditionaryForce finally secured the town and drove the Japs on down the Burma Road toward Lashio.

|

KILO 837 - Lungling is a walled city on the edge of the Burma Road. The largest populated center on the road west of the Salween River, it served as principal Jap supply outlet in the Salweencountry and was captured by the Chinese in November, 1944, after a six-month's battle. Translationof Lungling: Lung, dragon; ling, royal tomb.

KILO 823 - The village of Huangtsaopa offers natural hot springs which are excellent for bathing. the spa was utilized by the Japs, who built a large concrete communal bath which still is in use.

KILO 785 - Sungshan (Pine Mountain) is a 7000-foot promontory which was known as the Jap Gibraltarof the Salween. A Jap garrison of 2000 was exterminated here after three months of constant battlingon the steep slopes of the mountain. Aiding in this campaign were Chinese engineers who set off explosives,blowing the top off Sungshan and a large portion of the Jap garrison with it.

KILO 759 - Hwei Tung Bridge over the Salween River, is the lowest point on the Burma Road portionof Stilwell Road (Elev. 2960 ft.) The original bridge, built before the Burma Road, was constructedby a wealthy Paoshan silver mine owner who wanted a shortcut between his work and home. He contributed a sum of money, collected gifts from the others interested in the shortcut and securedsupport from the Yunnan government. When the Burma Road was built, its route was directed to utilizethe bridge.

KILO 668 - Paoshan (Protective Mountain) is an old walled city, extensively damaged by Jap bombingin 1942.

KILO 643 - The gate near the road at this point marks the spot reputedly used as a post for changingmessage couriers on the communications system established by Genghis Khan nearly 800 years ago.

KILO 565 - Here Stilwell Road crosses the Mekong River (Beautiful River) over the Kong Ko Bridge.The Mekong River flows from Tibet, parallels the Salween River on part of its course, forms a portionof the Indo-China-Thailand boundary and flows into the South China Sea at Saigon, Indo-China.

KILO 412 - Sprawled at the foot of 14,000-foot snow-crowned peaks is the town of Siakwan. This isthe commercial center of western Yunnan Province and the intersection of the Burma Road with caravantrails used by tea traders from Shunning to the south and Tibetan traders from the north. Beyondthe town are the icy blue waters of Erh Hai Lake, 30 miles long and trafficked extensively bysailboats transporting crude salt from mines north of the lake. Three towns fringe the lake - Siakwan,Tali and Sichow.

KILO 327 - Yunnanyi (yunnan, southern clouds; yi, station) is a small, open village of old buildings.

KILO 270 - This section of Stilwell Road where it crosses Tienatze Miao Po, is the highest point ofthe highway. Elevation 9200 ft.

KILO 228 - Chennan is a small walled town. The Japs, after capturing Singapore, named it ChennanIsland.

KILO 193 - Tsuyung, an old Chinese walled city in a level valley.

KILO 125 - I Ping Lung (one flat wave) is a small town with modern factories and buildings. Itsprincipal industry is clarifying and solidifying salt from the surrounding hills.

KILO 15 - Tien Chih Lake is a short distance south of Stilwell Road just outside Kunming. The lakeis plied by thousands of native boats. On the Western Hills, just west of the lake, are two Buddhist temples - Huating Temple and Taihua Temple.

KILO 0.00 - Kunming (kun, good omen; ming, bright) is the capital of Yunnan Province. It formerlywas called Yunnanfu. Once a little-known city, it has become, with Chungking, the principal havenof refugees fleeing from Jap tyranny on the occupied coast of China.

HISTORY, RELIGION & CUSTOMS

HISTORY

As you will see from themapin this booklet, Ledo is located in northeastern Assam, British India'seasternmost province. A primitive and backward region, Ledo is at the end of the line in more than one way, for you will notice as your convoy starts on the long journey to China that the railroadruns only a few miles and then stops abruptly.

The ammunition and war supplies that you are transporting to China came up this rail line fromCalcutta after a journey by sea of nearly 14,000 miles from the United States. It is the longestsupply line in the world.

A few tea plantations, a colliery and brickyard are in the vicinity of Ledo, but beyond that thereis nothing but thick, matted jungles and an occasional native village until you reach Burmese townslike Myitkyina, Bhamo and Namkham.

Ledo was named after the dingy bazaar near Headquarters. It has grown into a tremendous, sprawlingmilitary installation since the Americans came to this part of the world in December 1942. Prior to that time Outer Assam was a frontier tract, visited only by game hunters and gem traders. A specialpermit was required to enter the jungle, and travelers waived all liability for their personalsafety when they left Ledo.

Crossing the road between Ledo and Shingbwiyang are traces of the famous Refugee Trail, scene ofuntold suffering and sacrifice on the part of the Burmese, Indians and British who, fleeing fromthe Jap hordes during the dread monsoon of 1942, picked their way through the jungles towardsafety in Assam. Out of 30,000 men, women and children, starving and stumbling through theeternally dim wilds, only 20,000 reached a haven in India. Bones and belongings of the 10,000victims of this tragic exodus were left to bleach and rot in the moldy, leech infested jungles.

Burma, which is about the size of Texas, has had a colorful history, dotted by clashes between native chieftains and later with Siam, China and the British. Until 1886 the country was ruled by its own native monarchs, but as a result of the Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 the last portion ofindependent Burma was incorporated into British India on January 1, 1886.

Upon pacification of Upper Burma, the entire country was unified, and in 1897 was made a provinceof British India. The move was unfortunate, however, and a campaign for complete separation fromIndia bore fruit when, in 1937, Burma was made a colony. Under her new constitution, Burma hadbecome in all but name a self-governing dominion. With the exception of the Philippines, notropical dependent of any empire has attained so large a degree of autonomy.

In your trip over Stilwell Road, you will penetrate less than one-fourth the length of Burma.The region through which you pass is frontier country, merging with Yunnan, ancient provinceof Southwest China, an equally untravelled hinterland in normal times.

Although places in China along the Burma Road were visited by the trader Marco Polo as early asthe 13th Century, the commerce and business of the country has been centered in the seacoastcities because of their accessibility by water. Yunnan did not spring into the news prominentlyuntil Japan invaded China proper in 1937 and the civilians and government agencies fled to Yunnan.Chungking became the capital of free China, and Kunming the terminus of the Stilwell Road,contains important Headquarters. With China blockaded by sea, the only route open was over theBurma Road. When the Japs swept into Burma early in 1942, the last land route between Chinaand the outside world was sealed off for three years. On February 4, 1945 Maj. General Lewis A. Pick,leading a convoy of 113 vehicles over the Stilwell Road, entered Kunming, China, breaking thatland blockade.

PEOPLES AND CUSTOMS

You will see a strange mixture of people as your convoy winds its way toward Kunming, passingthrough regions which few Americans have ever been privileged to enter. Outstanding among thetribes to be seen in the Ledo-Shingbwiyang area are the Nagas, thick-legged, muscular aborigineswho abound the jungle hills. These scantily clad, primitive people bob along in a dog trot,carrying a native dau, a square-bladed knife slung across their middle. Headhunters only a generationor two ago, even today they engage in tribal wars and hang skulls of their victims in their nativedwellings. They are extremely friendly to Americans, however, and have proved invaluable in helping rescue pilots and soldiers lost in the dense thickets.

Farther on you will see the Kachins, fierce tribal residents of northern Burma. The Kachins resemblethe Nagas, but have finer features, and like them, live in bustees, bamboo huts built on stilts.They carry the long bladed dau and both men and women wear the longyi, a skirt-like attire whichfalls to the ankles. Kachins have served with our forces as scouts. Enjoying a reputation asferocious fighters, they resisted all Jap attempts to bring them into the fold.

Soon after you leave Myitkyina and cross the Irrawaddy, you will enter the Northern Shan States.These people resemble Chinese, simply because they are of Lao-Tai stock, blood-brothers of theSiamese and Tai of Southern China.

At Wanting, you will enter China and observe the cheerful, spirited people who have resisted theJap invaders longer than any of the Allied nations. Yunnanese peoples are the most numerousresidents in the area traversed by the Burma Road. However, mingled in the overall Chinese patternof Yunnanese are population groups retaining their own tribal characteristics, culture, sentimentsand dialect.

Besides the tribes resident in the villages along the Burma Road, the importations from other hsiens(districts) of workers and the infiltration of refugees from the east coast has brought about astrange mixture of peoples.

RELIGIONS

The Nagas and Kachins are native worshipers known as Animists. Their primitive state is reflectedin their religious worship, hence you will see no temples in the Patkai Hills or Upper Burma.The Kachins believe they are plagued by a variety of devils and villages have weird looking gadgetson top of thatched shrines as a tribute to things of nature.

The predominant religion of Burma is Buddhism. As you reach the Myitkyina area and go south you willnotice an increased number of temples and pagodas. At Namkham, in the ruins of the Temple of theGolden Eye, crouches a 40-ft. statue of Buddha encrusted with colorful, mirrored stones and coveredwith bright gilt.

Religion occupies a foremost part in the lives of the Burmese and is one of the reasons for thepicturesqueness of the country. Every town and hamlet has its own pagodas or monastery. Thespiritual head of every village is the yellow-robed pongyi, or monk.

In China you will see fewer temples, but at many places along and near the Burma Road there areimpressive Buddhist structures. At Tali, six miles off the road, are two pagodas, one of whichis off vertical like the leaning tower of Pisa.

Cemeteries are scattered along the route to Kunming, many of which are hundreds of years old.These graveyards, which have withstood the ravages of time, are revered by the Chinese and sprawlfor miles over the mountainsides. Near Lungling, the graves of the brave soldiers of the ChineseExpeditionary Force are to be seen, fenced in and decorated with flowers planted in old oil drumsin best Chinese fashion for utilizing everything retrievable.

Neither Burma nor China has a caste system like India. While there are distinct social stratas,there is nothing to keep the able, energetic and deserving Burmese and Chinese from rising abovehis neighbors.

JUNGLE NOTES

If you're a newcomer to Assam and Burma, your conception of the jungle probably is a Hollywood-izedprefabricated vision of a wilderness wherein tigers and pythons and cobras lurk behind each vine-entangledtree, bloodthirsty natives prowl in search of unwary safaris and Dorothy Lamour skips endlesslyup mysterious trails, fresh and vibrant in a silk sarong with garlands of orchids festooned abouther slender throat. And perhaps your imagination even tosses in a Crosby, groaning sentimentalballads, or a Hope engaging in gay repartee with chattering monkeys in tall trees.

But all that is dream material of which movies are woven - unfortunately so in the conspicuouslack of Dorothy Lamours in this corner of the world.

The jungle is not an exotic green wilderness of gigantic trees, rare flowering plants, swarms ofmonkeys swinging from vines, writhing snakes and vicious animals. The jungle, in reality, is talland dark and silent as death. It is an ageless confusion of tangle, matted undergrowth which confinesprogress to dim, narrow trails. There are snakes, tigers and leopards - even elephants, bears, bisonand rhinoceroses - but they are rarely seen. The worst enemies of man in the jungle are themosquitoes, leeches and mites.

Nowhere in the world are there more species of insects than in the jungles of Assam and Burma.It is almost as if Mother Nature uses this country as a proving grounds to try out new models of pests with which to plague humankind. There are besides the malaria mosquito, typhus-carryingmite and leech, such annoying and dangerous pests as ticks, wasps, hornets, bees, scorpions, sand flies, house flies, spiders, ants and hundreds of others.

Of the nearly 300 kinds of snakes known to inhabit the jungle, only 40 are poisonous. And, of these,only cobras, kraits and vipers are dangerously poisonous. However, snakes like seclusion and attackand bite only when they are trapped and cannot escape.

Scientists have classified more than 1500 species of vegetation in the jungle country through whichthe engineers have cut the Ledo Lifeline. Most common of the trees is the halong - a towering,white-barked hardwood which was logged by GI forestry outfits and used in the construction ofbridges and Army installations from Ledo to Wanting. Jungle housing facilities for the Army units onthe road were provided by bamboo, carpentered skillfully by native worker and GI's. Bamboo grows inclumps of a hundred or so stems, averaging between 35 and 80 feet in height.

There is beauty in the jungle too. In the late spring orchids and gardenias blossom profusely, witha gaudy background of flowering jungle trees. Birds and butterflies add swift dashes of color. Andthere is the ingenuity of the jungle creatures such as the vicious half-inch-long red ant whichbuilds its nest in trees by sewing leaves together into a huge ball.

But of all the discomforts and hardships handed the men who built the road through the jungles, themonsoon was the worst. The monsoon is a seasonal wind which blows over most of India and Burma fromthe southwest in the summer. In the jungles of Assam and Burma. the monsoon begins in May and endsin October. During this period rainfall exceeds 200 inches in many places, five times the seasonalprecipitation on the east coast of the United States.

These torrential rains inundate vast areas of the jungle, turning the land into a sea of mud.Downpours are followed by hot weather which makes the whole land steam. Clothing and tents moldand rot; leeches and mosquitoes come out in full force.

The monsoon plagued the builders of the Ledo Road more than any single obstacle. Coming with the fury of a cloud burst, tons of water rush down the mountainsides in a few hours, washing out fill-ins,overflowing the huge culverts, bringing trees and debris down the raging rivers to smash at bridgefoundations.

During the summer months the matted vegetation of the jungle grows with amazing speed. In a few days,a clearing or trail will be completely obliterated by the fast growing vines, trees, ferns and thorny undergrowth, accelerated by the heat and constant rain.

To-day, the area over which the Ledo Road winds looks relatively harmless, but venture a few hundredfeet from the highway and you enter a dim, matted world possessed by natures most vicious beasts,birds, insects and pests.

BUILDING OF THE ROAD

Unquestionably one of the engineering marvels of the world, the 1079 mile Stilwell Road encompassestwo separate projects. First, the 507 mile Ledo Road from Ledo, Assam to Wanting, China. Secondly,the Burma Road from this point to Kunming, a distance of 960 kilometers. The two projects are asdissimilar in construction as the problems encountered and the terrain over which they pass.

UNCHARTED JUNGLE - The Ledo Road was built through a vast uncharted area on which no records, accurate maps, rainfall data, characteristics of the rivers or types of soil were available.

To complicate matters, the construction was at the end of the world's longest supply line. Almostall supplies and every piece of equipment had to travel by boat from America, be unloaded inCalcutta, come by train over two different rail gauges, before being utilized in the building ofthe road.

COMBAT OBSTACLE - The next hurdle was the combat situation. As the road progressed, it was necessaryto interrupt the work to allow men and supplies to move over the route so that the Japs could be driven back. At times, the Engineers were so close to the front lines that lead bulldozers werearmor plated and survey parties carried heavy arms.

From October 1943 until January 1945, the road progressed from the 38 mile mark to the junctureof the Burma Road, a distance of 427 miles. This is progress of a mile a day over a route thatpasses through 102 miles of mountains.

During seven months from March through October 1944, about five times as much rain fell as isrecorded in one full year in America. In addition to the principal job, airfields, feeder roads,pack trails and combat roads totaling several hundred miles were constructed.

EARTH MOVED, DRAINAGE - Prodigious quantities of earth were moved by the white and colored engineersin building the Ledo Road. An Average of 50,000 cubic yards of earth were handled in the first 270 miles, totaling 13,500,000 cubic yards. With this much dirt, it would be possible to build a solidearthen wall three feet wide and ten feet high from New York to San Francisco.

If all the culvert pipe used in the drainage system of the Ledo Road were placed end to end, itwould form a continuous pipe line 105 miles long.

MUD, GRAVEL - One of the greatest obstacles faced was the lack of gravel or suitable rock to surfacethe road bed. The earth over which the road passes is a sandy loam that whips into a liquid mud.

It was sometimes necessary to haul gravel 25 to 30 miles from the river beds. It would take a stringof rail road cars 470 miles long to move the 1,383,000 cubic yards of gravel placed on the road.

BRIDGES, LOGGING - Ten major rivers and 155 secondary streams are bridged between Ledo and the juncture of the Burma Road, a bridge crossing for every three miles of road built. The 165 bridges(the minor stream crossings of Stilwell Road are not included in this figure) total an overalllength of about five miles. The longest floating bridge in the world crosses the Irrawaddy belowMyitkyina. A permanent floating bridge is used as the Irrawaddy is 60 ft. deep at the crossing andfluctuates 45 ft. between high and low stages.

Lumbering and logging operations were carried out on an unprecedented scale. When monsoon rains required the building of a two mile causeway, over 2,400 piling and 1,000,000 board feet of lumberwere cut, sawed, delivered and put into place in 30 days. Over 822,000 cubic feet of lumber hasbeen taken from the jungle for construction of the road.

The first 270 miles of the Ledo Road were forged through solid, virgin jungle, previously piercedonly by primitive Naga and Kachin trails. Below Myitkyina, a juncture was made with the oldBhamo Road, a narrow northern Burma trace. This road was only passable in dry weather for lightvehicles or ox carts. In their withdrawal from Myitkyina, The Japs not only destroyed all worth-while bridges on the road, but in the hill section they demolished the roadbed itself.Stilwell Road engineers have rebuilt all the bridges, widened, straightened and metalled this entiresection of the road to make it suitable for heavy truck traffic.

SIGNALS, MEDICS, QUARTERMASTER, PIPE LINE - Never before was a greater co-ordination between Servicebranches displayed then in the construction of the Ledo Lifeline. Adequate communications wereessential to keep the various engineering parties in touch with each other and with base headquarters.Signal Corps. soldiers, white and colored, worked feverishly through driving rains and waist-deepmud to erect communications lines and operate radio and telephone equipment.

The Quartermaster Corps. performed the prodigious task of maintaining supplies and transportingthem to the forward areas. The QM trucking companies, composed primarily of experienced Negro truck drivers, armed with rifles, kept a constant flow of food, ammunition and equipment movingforward day and night.

Pipe Line engineers began the construction of a pipe line that reaches from Calcutta to Chinatoday. These men braved thick jungles and raging torrents during the monsoon, bridging swollenrivers, traversing swamps and woodlands with a fuel line to carry precious gasoline forward.

Through it all, hundreds of Ordnance technicians, Medical officers, nurses and medics and troopsfrom other branches helped keep men and machines in fighting trim to rush the project tocompletion. Pontoon engineers fought the rushing streams to provide ferry service and erectbridges as fast as the road moved forward.

BURMA ROAD ENGINEERS - The Burma Road section of the Stilwell Road has a history all its own.Cutting over the Himalayan Hump, it is the newest of many communications routes developed by theChinese during the past 4000 years.

The Burma Road started from Kunming in 1920 along the general route of an old, little-used spiceand tea and opium caravan trail toward Burma. By late 1939 it was opened to Wanting, Yunnan Province border village, to which place the governments of Burma had built arteries to connectwith their Irrawaddy River ports of Bhamo and Rangoon and the railhead of Lashio. The course ofthe road is not new, for Genghis Khan and Marco Polo in the 12th and 13th centuries touched placesalong today's route.

Building of the road, starting shortly after the end of World War I, was not completed until a fewmonths before the beginning of World War II. The construction was done without engineering as weknow it. It was done by coolies on the concept that a road was anything that a truck could driveover in dry weather. Paving was three to five meters wide, consisting of layers of six inch stonesplaced by hand , covered with two inches of smaller stones as a wearing surface. More than 100,000people worked on the project from start to finish.

It was essentially a one-track, all-weather road when Americans began co-operating with the Chinesegovernment's Yunnan-Burma Highway Engineering Administration early in 1943. The small group ofAmericans, known as the Burma Road Engineers, assisted in technical advice, operational instruction,some supplies plus persuasion, friendship and personality.

Only eight pieces of equipment, scattered and in poor repair, were available. With this equipment,when it was actually put into service, were five American officers and 19 enlisted men, endeavoringto show the Chinese what could be done with machinery. The Chinese furnished 30,000 coolie laborersat a time.

In an effort to stop the Jap armies driving into Southwest China, the Chinese blew up the vitalSalween River bridge and destroyed the road by lining it with tank traps for 25 kilometers (Kilo709 - Kilo 734). Like the Ledo Road, the Burma Road also was used to transport combat suppliesto the forces on the Salween front who eventually pushed the Japs down the Burma Road to meetwith the Americans and Chinese Army in India.

Reconstruction work done between 1939 and the present time has included widening, elimination ofcurves, strengthening of bridges, reduction of grades and improvement of surfacing so that today thisreconstructed highway has been greatly improved over conditions that faced truckers several years ago.

MEN OF THE ROAD

On March 8, 1942, the invading Jap armies captured Rangoon, closed the last overland supply route toChina and surged northward to eventually overrun all of Burma. General Joseph W. Stilwell, lacking themen and equipment to offer suitable resistance, was forced to retreat. It is then that he made his famous statement, "I claim we took a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it's humiliatingas hell. I think we ought to find what caused it, go back and retake it."

It was obvious that a new supply artery would have to be opened if America was to carry out hercommitments to China. And in order to open a road, the Japs would have to be driven back.

The first step in the plan was formulated in October 1942, when Gen. Stilwell and Lord Wavell (thenGen. Wavell) met and decided the construction of a road from the railhead at Ledo would be anAmerican responsibility. Plans were drawn up hastily and submitted to Stilwell on November 5, 1942.On December 1 the advance contingent of Americans arrived in Ledo and thus was started a projectvisualized by Uncle Joe Stilwell as the only means of driving the Japs from Burma and re-establishingland communications with blockaded China.

No longer a project, but now a reality, a great measure of the success of the undertaking can be laidto Gen. Stilwell's keen foresight and determination to rectify the humiliation suffered when the cocky Japs swept through Burma and slammed shut the back door to China. Lt. Gen. Dan I. Sultan's work incarrying out to successful completion Uncle Joe's plans and Maj. Gen W.E.R. Covell's organization ofServices of Supply in the theater also played an important role in the opening of Stilwell Road.

The early period in the construction of Stilwell Road was fraught with difficulties and reversals.Equipment was short, the drenching monsoons swept away encampments, washed out the new roadbed, buriedbulldozers and caused dangerous slides. A large percentage of the engineering company cutting thepoint was hospitalized with malaria at one time. The project seemed hopelessly stalled.

On October 3, 1943, Col. Lewis A. Pick (now a major general) was flown from the States to assume commandof the road-building job. A Virginian by birth, Pick had entered the military service in 1917, servedin France during World War I. He had been called from the huge Missouri River Division constructionprogram involving a vast system of flood control.

On his first evening in Ledo - Oct. 16, 1943 - Gen. Pick summoned the key men of his command to a staffmeeting. "I've heard the same story all the way from the States," he told them. "It's always the same- the Ledo Road can't be built. Too much mud, too much rain, too much malaria. From now on we're forgettingthe defeatist attitude. The Ledo Road is going to be built, mud, rain and malaria be damned."

A series of bold measures were initiated immediately. Round-the-clock schedules were started. Oil was burnedin buckets when the supply of lights gave out. Road Headquarters was moved to the point. It was here thatGen. Stilwell paid his first visit on November 3, 1943. The road has progressed barely 50 miles fromLedo when Stilwell asked Pick when he could have a jeep trail cut through to Shingbwiyang. Sixty milesof the toughest mountain jungle terrain in the world lay between the point of the road and Shingbwiyang.

|

"I can't build you a jeep trail, but I'll build you a road that will handle truck traffic. Tell me whenyou want it," Pick said. "Can you get it through by the first of the year?" Stilwell queried. "Yes", wasPick's only answer.

On the morning of December 27, 1943, the lead bulldozer broke the tape at Shingbwiyang in Burma'svast Hukawng Valley, four days ahead of schedule, and a thrilling saga of the war was unfolded. Thetenacious, toiling engineers, working unceasingly despite mud, leeches, malaria and treachery of the jungle, had cut 54 miles of road in 57 days. A convoy of 55 trucks carrying Chinese combat troopsand equipment followed the lead bulldozer into Shingbwiyang, the first Allied soldiers to enter NorthernBurma by vehicle.

In the ensuing months, culminated when he rode into Kunming at the head of the first convoy to China, Pick planned boldly, followed through to swift completion and instituted many far-reaching innovationsin his determination to complete the project. He diverted engineers from work on Stilwell Road to cleara combat road through the jungle; he had depots set up to supply troops in the forward areas, and his engineers built air strips to enable us to gain control of the skies over Burma.

A plan was worked out with the Air Force to co-ordinate and administer air supply for greater efficiencyand increased tonnage. Under this pooling arrangement in June 1944, air lift tonnage was increased morethan 100 percent in 30 days above Air Force estimates.

From the beginning, Pick surrounded himself with able, hard-hitting officers and men. Col. Charles S. Davis, holder of the Legion of Merit and executive officer of the project until he assumed command ofthe Stilwell Road Motor Transport Service, carried out the sweeping plans for supply, and administeredthe huge undertaking. A graduate of the University of Missouri as a civil engineer, Davis was a construction engineer in civilian life, and his executive ability was utilized to the fullest.

Col. Robert Green, University of Illinois graduate and former blocking back for Red Grange, worked in conjunction with the road planners. Col. Green in charge of Road Headquarters, was in the field constantly,supervising, consulting and advising the engineers who cut the highway to China.

But the building of so vast a project as the Ledo Road was not the work of only a few. It required ablestaff officers, field commanders and thousands of troops, white and colored, of every rank and fromevery walk of life to complete the task.

Col. Robert A. Hirshfield, constantly working in the forward areas, planned and built the huge sub-depotsat Shingbwiyang and Myitkyina, enabling the advancing combat and service troops to have supplies andequipment on hand at all times. Col. DeWitt I. Mullett, commanding officer of a Quartermaster truckingregiment was long an adviser in transportation matters.

Lt. Col. Donald L. Jarrett was in charge of road maintenance and, with his men, battled to keep the highwayopen during the dread monsoon periods.

First American to march over the Himalayas was Maj. James H. Kaminer who, with 16 men, surveyed a possibleroute for Stilwell Road to China. Although in constant danger of Jap patrols and working with old and incomplete maps, Maj. Kaminer and his party completed their mission successfully. For carrying out this job, the major and his party were awarded Bronze Star medals.

To the thousands of brave and determined troops along Stilwell Road who toiled day and night the worldof freedom owes a debt of gratitude.Farther from home than any soldiers in this war, living in jungle country much of which never before hadbeen penetrated by civilized people, these men suffered the hardships of maddening rains, infecting leeches,danger from fevers and the monotony of endless jungle hours.

At the end of the world's longest line, they felt the lack of all comforts and luxuries, endured theisolation and, at times, had to look to the skies for food as air-dropping planes circled over remoteencampments.

Wrestling with snorting bulldozers, wheeling big cargo trucks, erecting communications lines, carryingand coupling fuel pipe, repairing arms and motorized equipment, hunting out the Anopheles mosquito instagnant jungle streams, flying across the jutting mountain peaks, routing out the dug-in Jap invaders,caring for the sick and wounded, and performing the thousands of other tasks entailed, was theassignment that the men of Stilwell Road carried out so that China could be re-entered by land andanother nail driven in the coffin of Japan's imperialistic aims.

MEN OF COMBAT

Graves are the milestones of Stilwell Road. For the price of this lifeline has been exacted in blood.Americans, British, Chinese, Indians and Kachins have fallen in making possible the road upon whichyou drive today. They lie in military cemeteries between Ledo and Kunming; they lie alone in gravesbeside Burma's dim jungle trails and on the sear mountainsides of China.

When American engineers took over the building of the Stilwell Road in December 1942, thousands ofveteran Jap troops controlled all of Burma and a portion of the Burma Road in southwestern China.Thus the success of the new overland supply route to the beleaguered Chinese was dependant not only onthe highest degree of engineering skill but on a full-scale, sustained offensive against an enemywho blocked the path of the proposed highway.

The Burma campaign was launched in December 1943 by troops of the Chinese 38th Division, American-trainedand equipped. The 38th marched up Stilwell Road as fast as the lead bulldozer, which was still working inthe Patkais, then cut down jungle trails to the Hukawng Valley where they engaged superior Jap forcesat Yupbang Ga.

This initial skirmish almost proved disastrous. The 38th was cut off. Surrounded completely, the divisionfaced annihilation. Reinforcements were rushed up from Ledo, however, and relieved the besieged 38th,defeating the Japs decisively in a five-day battle.

In January the Chinese 22nd Division joined in the battle of the Hukawng and a Chinese tank unit, underthe command of Col. Rothwell Brown, came over the unmetalled mountain road from Ledo. The tanks were drivenby Chinese soldiers who, a few months before, had never seen a train or an automobile. A few tankswere lost over the sides of precipitous gorges. Descending steep portions of the road, the tanks werelashed by cable to bulldozers which dug their blades into the surface of the road to act as brakes.

Fighting in Burma's matted jungles proved to be a succession of battles for trails. The campaign movedalong the narrow spearheads of these lines of communications. The adjacent wilderness was controlled by the troops in possession of these trails. The Chinese 38th moved on to Tabawng Ga, Nchaw and Kaduja Ga,in the Maingkwan Plain sector. Elements of the 22nd rolled up advance Jap units along the trails andmoved toward the Taro Plain, western area of the vital Hukawng Valley.

On Feb. 9 ,1944, Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill's Marauders left Ledo on their march up Stilwell Roadto fames as jungle fighters whose cunning and stamina in harassing Jap lines of communication played abig part in the success of the Burma campaign.

Organization of the Kachin Rangers also began early in 1944. Intense hatred for the Japs by the Kachins,who always have been a proud, independent people, was thus utilized to good advantage in the Burma warfare.Wise in the way of the jungle, the Kachins acted as scouts and guides and worked far behind the Jap lines,establishing road blocks and severing communications.

But through the early days of bitter jungle fighting, Americans had little conception of what was goingon in this far corner of the world; they had no idea of the type of country men were fighting and dyingfor. The ignorance of conditions in Burma is best illustrated by stories carried in the American presswhen the Chinese fought their way into Tagap Ga, a tiny native settlement consisting of a handful oframshackle bamboo and corrugated iron dwellings. As Chinese troops entered the village, newspapersin the United States proclaimed "Chinese army now fighting in the outskirts of Taipha Ga."

As the months passed, the Burma campaign progressed ahead of schedule. Walawbum and Maingkwan fell tothe combined American-Chinese operations. Col. Phil Cochrane's First Air Commandos and Gen. Wingate'sChindits started offensives far behind the Jap lines in the Chindwin country. Between Maingkwan andWalawbum Col. Brown's Chinese tank forces killed more than 2000 Japs in a ferocious engagement, thenused bulldozers to cut a road through the jungle for an armored assault on Walawbum.

By March 15, the Jap supply base of Tingkawk Sakan was taken despite bitter resistance and by March 19Jambu Bum Pass had fallen. Jambu Bum, which was the maximum point of penetration the Japs had plannedto permit the Chinese and American forces to make before the monsoon, cost the Japs 4000 killed.Shadazup, Warazup, and Malakawng, strongpoints in the Upper Mogaung Valley, were quickly liquidatedafter the fall of Jambu Bum.

But as the combined Allied offensive gathered momentum in the wilderness of North Burma, the Japs counteredwith a drive toward Imphal and Assam which threatened to sever communications between Ledo and Calcuttaand pinch our Burma armies off from the rear. The British 14th Army aided by American combat and cargoplanes, went into action on the Imphal Plain and stemmed the Japs' abortive dreams of conquest of India.And, with the threat to the rail supply line from Calcutta imminent, GI railroaders went about theirdaily job armed with rifles and carbines while Chinese 30th Division troops and American Quartermasterand Ordnance men patrolled the rail line from Digboi to Chabua and southward.

On April 27 two forces, composed of Marauders and Chinese, started out on Uncle Joe's "Myitkyina Gamble."This outflanking attack on the Japs' Irrawaddy River fortress required scaling the 7000-ft Nam HykitPass and a 20 day forced march over little-known jungle trails before the troops reached the Myitkyinaair strip. The expedition encountered a party of Japs at Naura Hyaket Pass and later annihilated a Japgarrison at Ritpong. By May 16, the task force reached Namkwin River and the following day they tookthe Myitkyina air strip and ferry in an assault which caught the Japs napping.

With the air strip in our hands, engineering equipment, supplies and reinforcements made up mainly ofStilwell Road engineers - were flown in by transport and glider. Chinese troops took Myitkyina railroadstation, but were driven out to positions 800 yards west of that strong point as the Japs rushed inreinforcements.

The battle for Myitkyina settled down into a bitter siege. The Marauders, weakened by malnutrition,disease, and fatigue, were relieved late in May by two Stilwell Road Engineer units and infantry replacements. Chinese 14th Division troops and Chinese 22nd Division artillery were flown in. British ack-ack crews arrived. But still the Japs resisted stubbornly from a network of concrete and sandbagpillboxes set as far as 30 feet underground.

American engineers suffered casualties as they worked on the air strip. Fighter pilots, ATC and Combat Cargo crews risked their lives every time they took off or landed on the rough, narrow strip. There werenumerous crack-ups but still cargo and men continued to arrive in unprecedented quantities. Col. Seagraves's hospital unit opened for business on the edge of the airfield a few days after the battle began. Mired in mud and sprayed by shrapnel and sniper fire, Seagrave's surgeons worked under umbrellasheld by Burmese nurses. Litters elevated on packing cases served as operating tables. Casualties were flownto hospitals in the rear areas after emergency surgical treatment has been administered.

As the siege of Myitkyina continued into June, troops of the Chinese 38th Division, despite torrentialmonsoon rains which inundated the swampy Mogaung River country, captured Kamaing and moved on down thedry weather road from Warazup toward the railroad town of Mogaung. Late in June, elements of the British77th Brigade, bolstered by Chinese 38th Division troops, captured Mogaung.

During July remnants of the crack Jap 18th Division, which had infested the Mogaung Valley, were disposedof and jeep-powered railroad service between temporary railheads outside Myitkyina and Mogaung was instituted. On July 26 a force of new Marauders, strengthened by veterans who had been flown back into battle from India, launched a drive on Sitapur, north of Myitkyina, and broke through Jap defensesto the Irrawaddy, thus completing encirclement of the enemy. On the afternoon of August 3, Myitkyina fell,ending a 79-day siege.

The fall of Myitkyina broke the back of the Japs' defense plans for North Burma. In September, the British

|

As the British 36th advanced down the railway corridor, The Chinese 38th Division spearheaded the ChineseFirst Army in an offensive aimed at Bhamo. The Chinese Sixth Army struck swiftly through Schwegugals andSchwegu, west of Bhamo. On December 15, after a 26-day siege, Bhamo fell and the third largest city ofBurma, reduced to rubble by merciless artillery fire and bombing, was ours.

By mid-March of 1945, the British 14th Army, driving across Central Burma from Imphal, had taken Mandalay,Burma's second largest city, and then drove relentlessly south to recapture Rangoon, thus virtuallyending the campaign in Burma.

Meanwhile, in collaboration with the Burma campaign, Gen. Stilwell formulated plans to drive the Japs backfrom the portion of the Burma Road which they occupied from the Salween River in western Yunnan Provinceto Lashio. The plans were translated into action on May 11, 1944, when the Chinese Expeditionary Force,with tactical and strategic assistance and supplies furnished by the American Y-Forces Operation Staff,under the command of Brig. Gen. Frank Dorn, crossed the Salween on a 130-mile front.

During the first three months of the Salween campaign on the world's highest battlefield - the 12,000-ft.Kaoli Mountain Range - the Chinese liberated more than 150 populated places and regained 10,000 square miles of territory. By July, strong Chinese forces were besieging Jap garrisons at Tengehung, Pingka and Sungshan Mountain.

Sungshan fell to the Chinese September 7 and Tengehung and Pingka were liberated shortly afterward. Troopsfought their way into the walled city of Lungling on June 10, but the Japs recaptured the city June 17.It was finally occupied by the Chinese on November 3.

With the fall of Lungling, the Chinese Expeditionary Force pushed rapidly southward. Road blocks had beenthrown across the Burma Road, both north and south of the open town of Mangshih, in June, and troopsadvancing south from Lungling took the town on November 20.

Beyond Mangshih, the Chinese encountered fanatical Jap resistance in the barren Wanting hill country.The enemy was forced back slowly, however, and the Chinese entered Wanting early in January. Again, the Japs regrouped and took the town back, but a week later the blue-uniformed soldiers of the C.E.F. re-enteredthe border settlement and pushed the decimated Jap defenders down the Burma Road past Mongyu, junctionof the Ledo and Burma Roads.

During the closing weeks of the Salween campaign, the Chinese Armies of India wheeled to the east fromBhamo and began clearing the 163-mile stretch of road between that Irrawaddy River port and Wanting.And the American Mars Task Force under the command of Brig. Gen. John P. Willey, went into action,marching against the Burma Road terminus of Lashio.

The Jap army of northern Burma was in full retreat. Namkham fell. On Jan. 10, 1945, the Y-Force andChinese Armies in India linked up at the Shan village of Meng Mao. Mopping up swiftly, the troops tookMu-Se on January 22 and cleared the last section of Stilwell Road on January 27, when the Burma-LedoRoad junction of Mong Yu fell. The following day, January 28, the first overland convoy to China inthree years, passed within one mile of the front lines to cross onto Chinese soil at Wanting, on itsway to Kunming from Ledo.

Units of the Mars Task Force meanwhile had established road blocks on all escape routes for the Japsretreating toward Lashio. Few Japs lived to escape from North Burma. Early in March, men of the Mars Task Force and Chinese troops captured Lashio, gaining complete control of the Burma Road. Stilwell'sover-all strategy was realized - the securing of a land route to China was complete.

Layout, illustrations and map by Cpl. Sydney Kotler.

All photographs by men of the 164th Signal Photo Company.

Special thanks to Joan Isham, niece of Colonel Charles S. Davis, for her gift of the booklet on which this page is based.

Adapted for the internet from the original 1945 booklet Stilwell Road - Story of the Ledo Lifeline

Copyright © 2004 Carl Warren Weidenburner

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE CLOSE THIS WINDOW

Visitors

Since October 31, 2004