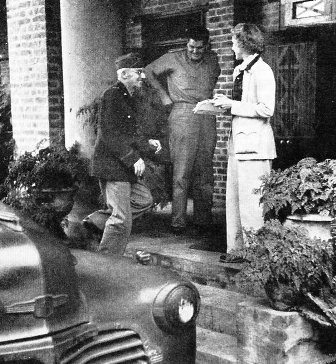

The Chinese sentry at Stilwell's Maymyo headquarters, just after giving his American commander a big grin, pulls himself extra stiff and wipes the smile off his face.The white men are Stilwell aides, Colonels "Pinkie" Dorn and Frank Roberts. |

Scroll down or select... PART ONE PART TWO |

General Stilwell (right) jokes with his American-born Chinese aide, Lieutenant Richard Ming-Tom Young, of the U.S. Army, under a picture of the Alps, in the mission living room of Maymyo headquarters.Stilwell wears the three stars of lieutenant general. General Stilwell (right) jokes with his American-born Chinese aide, Lieutenant Richard Ming-Tom Young, of the U.S. Army, under a picture of the Alps, in the mission living room of Maymyo headquarters.Stilwell wears the three stars of lieutenant general. |

At Dum Dum airport at 1 p.m. I boarded a CNAC Douglas Army transport plane for the five-hour flight toLashio. All but seven of the bucket seats at the rear were flapped down to make room for the cargo - 20 burlappedtin cases of currency for the coffers of Chungking. My fellow passengers were six shaven-headed Chinese soldiersin khaki shorts.

Three hours out we passed over the south-running Chin Hills, into the Irrawaddy Valley where, north of Prome,the British are fighting under Sir Harold Alexander. After a time we passed over another chain of parallelmountains which sharply separate the Irrawaddy from the Sittang Valley. There the armies of GeneralissimoChiang, under Lieut. General Joseph Stilwell, are holding north of Toungoo. From the air the topographyof this battleground is painfully clear: Burma, mountain-rimmed, lies like an elongated teacup, stretchingnorth to south along the Bay of Bengal. Over this teacup rim, over these narrow muddy passes, no modern troopsor mechanized units can come from India. And now no supplies or troops are going up the valleys (whose onlysea mouth is Rangoon) because the Japs are coming up. There is no place for supplies or troops to come down from,except China, down the Burma Road, down the road to Mandalay.

Just as dusk began to fall we spotted Lashio's big clay field. We circled over the small city once and thenroared in. The minute we landed I realized that something unusual, something important, had just happened.U.S. Colonel Haydon Boatner, in charge of incoming American CNAC passengers, detached himself from one of themilitary groups and came up to me smiling broadly. "You're the luckiest journalist in the Far East,"he said. "Guess who just landed from Chungking on this field ten minutes ago? General Stilwell and -."He paused dramatically, "The Gissimo!" The news was really big: Madame Chiang had also come with Stilwelland the Gissimo and the next morning they were all leaving Lashio for Maymyo, Allied headquarters in Burma,where the high command (said Boatner) would have "a once-for-all powwow" and then go out to the fronts andgive their troops a "fight talk."

Lashio headquarters is a two-story wooden building with the office and mess on the second floor.Officers, Chinese and American, were clumping up and down the stairs continually. I insinuated myself into theup-flowing stream and at the top of the lamp lit wooden staircase I found General Stilwell leading a flightof Sino-American officers down. He was wearing an overseas cap on his close-cropped, grizzled hair, smokinghis interminable cigaret in its long black holder and chewing gum rapidly. "Hullo, Hullo," he said brusquely."Burma is no place for a woman." I started to give him an argument but he was already halfway down the stairs.At the bottom he turned. "Tomorrow morning at dawn I'm driving to Maymyo. If you can get up that early you canjoin me," he said with half a snort, half a laugh, "on the Road to Mandalay."

Stilwell's staff eat a frugal dinner in their Maymyo headquarters with Clare Boothe (foreground).At end of the table sits Brigadier General Hearn, Stilwell's chief of staff. Stilwell's staff eat a frugal dinner in their Maymyo headquarters with Clare Boothe (foreground).At end of the table sits Brigadier General Hearn, Stilwell's chief of staff. |

Lashio to Mandalay, Monday, April 6

At 4:30 a.m. those of us who were driving to Maymyo went into the mess for breakfast. On the stained, homespun tablecloth were pots of something black but sufficiently hot so that it passed for coffee,plates of crumbly bread, stiff oleomargarine, thin fruit jam and coarse pork and eggs, fried sunnyside-up.General Stilwell, Colonel Frank "Pinkie" Dorn, his tall, handsome, Chinese-speaking aide, and LieutenantYoung are with chopsticks. "Now this," said Pinkie Dorn, adroitly folding the crinkled white edges ofhis egg over the tremulous yellow yolk with his chopsticks, "is the acid test for an old China hand!"And with a lightning twist of the wrist he nipped the egg, intact, into his mouth.

General Stilwell's leathery face wrinkled in disgust. "Dorn," he said, "is a born show-off." Dorn was hurt.He felt that just because "Uncle Joe" could smoke a cigaret, chew gum and eat a fried egg with chopsticksall at the same time, it was not quite sporting to belittle his subordinate's lesser talent. The Generalfelt that was not the point. He suggested that Dorn was not completely satisfied with a creditable enoughexhibition of manual dexterity, he had a deplorable tendency to believe that his ability to eat a softlyfried egg with chopsticks made him an authority on the whole Chinese question.

Then General Stilwell said, "We have five hours on the Road... Let's be going." He had abandoned his overseas cap for a high-peaked campaign hat which he wore at an almost Marine Corps. slant over hisspectacled eyes. I followed Dorn and the General into the black offices towards the stairs. In the cornerof the office Stilwell stopped and, in the white light of Dorn's flash, knelt by a little trunk on thefloor. He put back the lid. It was full of small leather boxes, like jewel cases. He opened several ofthem. Crowned in the light of Dorn's flash on their soft, dark velvet linings, lay bright-ribboned medals,the gleaming and glowing medals that the United States of America bestows on fighting men for braveryand valor on the battlefield. He chose a Distinguished Service Cross, snapped the lid, dropped it in hispocket. "Who gets that?" "A young Chinese Lieutenant who led a battalion in a counterattack at Toungoo.And damn well deserves it." Then Dorn handed him a couple of Purple Hearts and he said grimly, "Bettertake a Silver Star of two in case," and closed the trunk. The contents had not been much depleted. I saidso. General Stilwell said quietly, "The U.S. isn't handing these out like cigaret coupons. These thingsstill mean something." For a fraction of a second the stab of Pinkie Dorn's flash seemed to strike UncleJoe's breast, as he straightened his small, lean body and turned to go. There, bright against the darkkhaki, was a double row of ribbons: The Distinguished Service Medal, the French Legion of Honor, theVictory Medal with three bars.

As we went down the stairs I recalled Napoleon's remark to one of his generals when he created the Legiond'Honneur: "With these bits of ribbon a man can build an empire." Dorn said, "It'd going to take more thanbits of ribbon to hold our empires together now."

Dawn had not yet began to streak the Lashio hilltops as we set out down the dusty, bumping, twisting roadto Maymyo in a rattling, very old Ford. I thought of the British and American major generals in Delhi,driving handsome, gleaming, red-leather-upholstered, seven-passenger Cadillac's, with smart flags flying overthe polished fenders. Yes, India was a long, long way from China's war. The Ford was driven by a brown-skinned,hook-beaked, somewhat ragged looking civilian. Stilwell said he was a Persian who had somehow found his wayto Burma. The Persian's name was "Saidie." He had written it in black ink on the back of the sun helmet hewas wearing. On the brim Saidie had written these words: "Men pass by with word and deed, What is left isearth and seed. TRUST NONE BUT GOD." Stilwell said that God's purposes were so often inscrutable he would liketo add the Chinese and the Russians to the one we trusted.

Behind us in a second car came Lieutenant Young, a Chinese liaison officer and the four bodyguards with tommyguns who had been assigned to Stilwell by the Gissimo. A little later the car passed us on a road bend. Twoof the guards were leaning way out the windows. "Carsick already," Dorn said disgustedly.

Now on the temple-dotted road to Mandalay, the sun came up in a hot mist behind the tamarisks and bamboos andbanyan trees. It turned the ghostly gray, needle-spired pagodas with their cross-legged gods pale pink, rose,then golden. Then they became blazing white and chalky under the unrelenting sunshine. Pinkie Dorn chattedon in his witty, cynical fashion, telling stories of American and Chinese and British contretemps on theToungoo front. And Stilwell, lighting cigaret from stub, chuckled, grinned, snorted, interjecting his constant"Yep! Yep! occasionally interrupting Dorn to correct him, always in the direction of more exactness, accuracy.

And I listened and talked too, but the question was always in the back of my mind: "Why is an American generalleading Chinese armies in Burma?" Here is a question millions of Americans are going to ask - if the Battle ofBurma is lost. Why, after four and a half years of leading his own troops in battle, why, possessing as he did

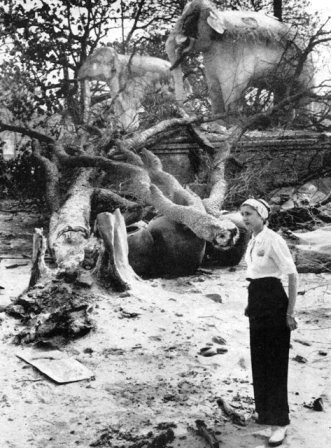

The ruins of Mandalay, after the severe Japanese bombing of April 4, are inspected by Correspondent Clare Boothe.The pair of plaster elephants and the row of white jugs are all that is left of an old Buddhist temple.Fire has blackened the landscape. The ruins of Mandalay, after the severe Japanese bombing of April 4, are inspected by Correspondent Clare Boothe.The pair of plaster elephants and the row of white jugs are all that is left of an old Buddhist temple.Fire has blackened the landscape. |

I could find no answer to this question in my own mind as we drove those five dusty, hot hours down the Mandalay Road. Then, rising steadily up, up into the winding Shan hills, we came at last to the cool reachesof Maymyo, the little hill station which was once the summer capital of peaceful Burma.The air was soft and balmy, heavy and sweet with the scent of flowers. Finally, at least, East and West meetin Maymyo. Roses and poinsettias, eucalyptus and larkspur, frangipani and honeysuckle commingle their odors andblooms. And then as we turned into the gateway of the Baptist Shirk Memorial Rest House, the big red-brickmission house hung with brilliant purple bougainvillea vines, which houses Stilwell's headquarters in Burma, Ifound part of the answer to my question of Uncle Joe there, found it, or rather saw it in the face of a boy,the bland moon-face of a Chinese guard who came stiffly to attention. So rigidly and smartly did he bringhis bayonet up across his sturdy breast, it almost slit the tip of his flat nose. His eyes glittered suddenly,brightly, happily. His young mouth fought against a wide and friendly smile as he saw U.S. General JosephStilwell alight from his car. This was Uncle Joe, who had lived at the front with his Chinese brothers, atetheir food, shared their dangers and would, if need be, shoulder their defeat. This was Uncle Joe, a hostageto fortune, a flesh-and-blood offering, representing in his person, in the persons of his staff of officersand technicians, all the goodwill of a mighty but late-starting nation - and the planes, the tanks, thesupplies, even the doughboys that would come one day.

However illogical militarily the Stilwell command in Burma might be, I thought, however useless in thiscollapsing area of war all Stilwell's professional skill may seem, the smile on the face of the guard at theBaptist Mission proved this: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Gissimo understood their peoples well when they dramatized, in the person of Stilwell, the fact that from here out Americans will fight side by side with theChinese.

It is good to see so many of my Clipper companions here. Colonel Frank Roberts whose thick, black-rimmedglasses give his keen face such a mild and professional look; little chirper Colonel George Townsend, whotalked all the way across Africa about the charms of "Gay Paree" in the last war; giant-framed BrigadierGeneral Hearn, called "Long Tom," chief of staff; dour and taciturn Colonel Sandusky.

There were 30-odd officers when we sat down in the mess for luncheon, including a sprinkling of Chineseliaison officers. The food is not bad, soup, meat (not identifiable underneath the tomato sauce, probablymutton or goat), potatoes and peas. And strawberry shortcake. Dorn said: "What, boiled strawberries? Wehad fresh strawberries last week. What the hell goes on here?" Roberts said: "They began to bomb Mandalayon Friday. They finished Saturday. The refugees are streaming up this way now. Doc Williams says they'recarrying cholera with them everywhere they go." "That's right," the little sandy-haired doctor said, "youboys have eaten your last fresh food. Comes the Jap, you eat boiled strawberries and like them!"

After lunch Stilwell and a good part of his staff disappeared. It seems the Gissimo and Madame Chiang havearrived and all afternoon what everybody calls "The Big Pow-wow" is going on - the talks that will decidethe fate of Burma.

I went up to my room to unpack. My room, in a little wing on the second floor of the mission, is a simple affair. An iron bed covered with netting, a desk, two chairs, a rickety dresser. There are several chromosof Alpine mountains on the walls, one electric light bracket. A bathroom adjourns, which I share withGeneral Hearn. It is a row of wooden-seated metal cans, a dented tin basin, with one spigot out of whicha dark-brown lukewarm trickle runs, an iron tub, also with one spigot, out of which no water runs at all.

At 3 o'clock George Rodger, the LIFE photographer, arrived in his jeep. He is a good-looking young Englishmanwith a browned face and sunburned, very long English legs. He said he was just back from the Irrawaddy front.He was discouraged about the pictures he had gotten - or rather the pictures he had not gotten. "This isn'ta cameraman's war," he said. It was almost impossible to get good action pictures in the clear. "It's allfought in the black and shadowy jungle, chaps prowling around in little groups and all that." It was a sort ofAmerican Indian warfare, he said, except that the Japs, instead of carrying bows and arrows and going barefootand wearing loin cloths, carried tommy guns and trench mortars and wore sneakers and gym shirts. He said howdangerous it was to motor on the road to the front, for even before you reached it the bullets of Burmese snipersor Japanese infiltration parties might whistle about your ears or a low-flying Jap plane would swoop down andmachine gun the road. And when you did reach the front, he said, nobody quite seemed to know where the front was,except that at any given time it was someplace forward of forward headquarters. He said he had managed to getsome pretty exciting pictures of towns the Japs had bombed as he came through along the line - Thayetmyo, Magwe,Meiktila - although, he said, he had always missed getting the best action pictures as shortly after the bombingsbegan he generally put his camera aside. There were never enough hands, he said, to help pull the wounded out ofthe flames and ruins. So he always found himself as a lifesaver or a fire fighter when the best shots were to bemade. And, he said, After you've been doing that for three or four hours, you're too tired, too sick to yourstomach, too disgusted with everything to take pictures anyway. I asked him if he had seen the bombing of Mandalayand he said no, he'd just come through in his jeep the night before. "But it's still burning," he said. Then Isuggested we drive over to see it.

Traveling in a jeep at 50 miles an hour, the wind races against your face too hard to talk. And if you are notaccustomed to it, sitting perched on a hard high metal seat with no doors to lean against seems definitelydangerous. It is apparent that Rodger is a seasoned jeep driver, but to me, as we rushed down from the Maymyo hills, clipping past trucks, rounding bends on two wheels, he seemed the most reckless driver I had ever sat beside. Presently it grew hotter and after about an hour, when we reached the flat road to Mandalay, theperspiration began to drip from my forehead faster than the hot dusty wind could dry it.

Yesterday, what did I know of Mandalay? Yesterday, to me it was just a Kipling song, an Empire sound. For what do most Americans really know of Mandalay, except this, perhaps: from Moulmein to Mandalay the courseof the Empire took its hot triumphant way, when Kipling was a war correspondent given to writing wondrousjungle jingles before this century began. I knew, of course, a few scattered facts that had impinged themselves on my mind through the years: population, 150,000, predominantly Buddhist, famed for its temples and crowdedmarket places.

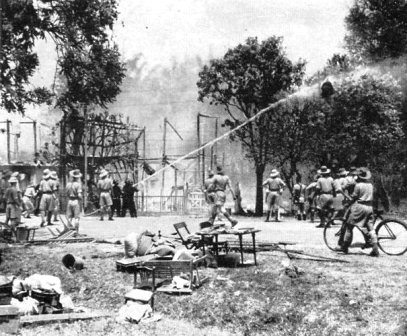

The fires of Mandalay are fought without much effect by the Burmese fire department and British Imperial soldiers, while civilians gather up their salvaged household goods. The fires of Mandalay are fought without much effect by the Burmese fire department and British Imperial soldiers, while civilians gather up their salvaged household goods. |

Tonight, what do I know of Mandalay? Well, not more than yesterday. For tonight there is no Mandalay.

I smelled it before I saw it. My eyes were fastened on the blue thrust of the lazy, pagoda-sprinkled, peacefulnorthern hills about its outskirts. Then suddenly the smell brought my eyes down from the hills, down to theleveled ruins that rushed upon us as the jeep tore into the town. It was to me a smell not unfamiliar. I remember, one hot summer, when I was a child, a dog died under our veranda porch. For some reason, it wasseveral days before someone cleared through the porch vines to cart it away. It was that smell. But athousand times magnified until it seemed, as we whirled through the streets, all creation stank of rotting flesh.

Monasteries, bazaars, houses, temples - how had they been? I would never know. As far as the eye could see it wasmet with a mass of smoldering gray and white charred timbers, twisted tin roofs, and everywhere the ashen limbsof fallen trees, burning like the bones of Indians on their burning ghats. A few buildings gutted, but not yetconsumed, still flamed and crackled against the sky. Rodger said, "There are 8,000 bodies concealed in these ruins. Here and there on the side of the streets lay a charred and blackened form swaddled in bloody rags, allits human lineaments grotesquely fore-shortened by that terrible etcher - fire.

Now and again we saw something still standing: a great blackened pair of temple elephants or giant sacred marblecats. And the mile-long 26-foot high red-brick walls of Fort Dufferin that enclosed Government House and Thebaw'swondrous Palace were still intact. But in the long green moat that surrounded the fort, where lazy lotus padsdrifted on the hot green scum, there floated many strange and hideous blossoms culled by the hand of death.The green little bottoms of babies, bobbing about like unripe apples. The gray, naked breasts of women, likelily buds, and the bellies of men - all with their limbs trailing like green stems beneath the stagnant water.Neither Rodger nor I pointed a camera at these fearful indecencies. To refrain from doing so seemed the onlygesture of respect we could pay these nameless dead. Not to record them on film seemed to grant them a burialof sort. How many inhabitants had I thought Mandalay had - 150,000? In that town today, we saw only 20 or 30people on all the streets. A few natives on bicycles, a handful of Burmese Rifles, and a dozen or so Poonghies:Buddhist priests with shaven heads, wearing sleazy bright orange silk robes, carrying battered black umbrellas.As they strolled through the smoking town, they looked like those dancing, jointed little favors one setson a Halloween table, decorated with skeletons and burning bowls. (it had begun on a witches' Sabbath, the Walpurgis Night of Mandalay.) We came to a place where the vultures were wheeling thick overhead. Rodger said,"There's the railroad station. They didn't get much of the tracks or the cars, but they did get about 1,500Prome refugees waiting for the trains to India, camping on the platform and in the yards. Shall we go in?"I said, "No, let's go home now."

We motored back through destruction's acres. We passed a small wooden building that had been untouched. SomeBurmese Rifles were sitting on the porch, smoking. Close by the porch lay the blood-clotted body of a girl.One hand rigidly clawed at the sky. I said, "Why in God's name don't they bury them?" Rodger said that in theirGod's name they couldn't. Burial of the dead, he said, was reserved to certain priestly groups and castes.

In the cool of the evening we came to Maymyo again.

We had been at dinner time minutes when General Stilwell came back from his long day's councils of war withthe Gissimo, General Alexander, Madame Chiang, and the Allied staffs. His wrinkled, shrewd face looked tired,but he was smiling as he nipped into his place at the head of the table, before the junior officers couldquite get on their feet. Colonel Roberts, Dorn and he exchanged long glances, and "Long Tom" stopped eatingfor a moment and stared over the tops of his specs. They know Uncle Joe's face better than I do, because theyfound apparently the answers they wanted there. A second later they went on "passing-the-bread-please."

But I said, "Well General, were the pow-wows a success?" He laughed. "Yep," he said, "Yep, Yep, Yep. The Gissimohanded it to everybody including his own generals straight. So did Alexander. So did I. And Madame Chiangtranslated it all, straight, too. Without pulling a punch. Yep. Everybody took it right out of the spoon."He laughed again. I could report to my constituents, he said, that the situation is now well in hand. Then hiseyes twinkled keenly behind his silver-rimmed glasses, and he began to eat lustily.

"That's nice, General," I said, "but - will it last?" Roberts kicked my ankle under the table. GeneralHearn stopped eating. Dorn grinned impishly. We all waited a long second. Then General Stilwell said, "Nope.It won't last long. It can't last long." Then he said, every minute more it could be made to last meant thatmuch more time gained for an R.A.F. air force to be assembled somewhere in India, for A.V.G. reinforcementsto reach Loiwing and Kunming, for Brereton's bombers to swing in again on Rangoon. Rangoon is the strategicheart of Japanese effort in Burma, he said, and if Rangoon could ever be knocked out before the Japs can entrench there, and before the Japs can build supply lines into Burma through Thailand, Burma might be held."Time, time, time," he said, that was what he was fighting for. Burma, he said, was the key to the Far East - the gateway to China, and China, with still-enormous reserves of manpower and great potential air bases, was theplace from which we could best get at the Japs. Wherefore, he said, he thought Burma was the most vital frontof the whole Pacific war, and then he said, laughing, "But every general thinks the front he is on is themost vital."

After dinner, Uncle Joe and Pinkie Dorn and Young disappeared to his office. The rest of us sat in the living room of the mission talking and eating peanuts out of a great wastepaper basket that stands by the fireplace.The only sour note struck tonight was little Colonel Townsend's. We were talking about the "success of thepow-wows," Townsend, who had been definitely brooding, suddenly said, "I don't see what's happened here inMaymyo today to change the situation on the Irrawaddy front." A liaison officer who had just returned from theIrrawaddy Front, said, "If you mean they don't fight - you're g-d-wrong! The Sikhs, the Gurkhas, theBritish there are putting on a hell of a show. Boy, they're taking it! Guts. They've got that all right."

Somebody sang softly, "We can't give you anything but guts, ba-bee - That's the only thing we've got plenty,ba-bee..." And someone else insanely added, "Then I viscera in Dixie, Away! Away!"

George Townsend said he didn't deny that everybody was being damn brave, what he meant was that they and wehadn't developed any other answer to infiltration except defiltration anywhere. "You've got to face it," hesaid gloomily, "The Jap is a smart customer."

There are no cigarets, candy, and chewing gum in the mission. They all complain about that. But they do not,oddly enough, complain because there is nothing to drink at all. Not even beer. How different from Delhi andCalcutta, where every officer, American and British, consumes chota-peg after chota-peg in his evening hours!"We haven't had a drink since we left Chungking a month ago," Roberts said. He thought perhaps some Scotchcould be borrowed from British headquarters if they "really wanted to," but "Uncle Joe is no drinker, and anyway,"he said, "we get along all right without it, you see."

Colonel Roberts was the officer "on duty" tonight. That meant that, after the others went to bed, he slept nearthe telephone on the couch in the living room, gun by his side.

I sat up and talked to him awhile. I asked him what had become of Lieutenant Kohler, the youngest member of the mission who had spent so much of his time reading Kipling on the African Clipper, coming out. I rememberedhow young Kohler had said, "Listen, this guy Kipling was all mixed up on his geography. He said he was standing'by the old Moulmein Pagoda - looking eastward to the sea.' Then the dawn couldn't have beencoming up 'like thunder outer China 'crost the Bay,' because China then had to be on the west, with the bayin between."

Roberts said that Kohler knew more about the future of Asia than any of us know. Kohler, the youngest, wastheir first casualty. He had been killed when a CNAC plane, taking him to Chungking, had crashed on the fieldat Kunming.

Then we talked of Kipling's Burma, and the Mandalay he had never seen. And the colonel said that when he hadtaught poetry and literature at West Point, Kipling had not been such a great favorite of his, but that nowwhole lines kept coming back to him in the night, hauntingly pregnant with new, unhappy meaning.

Finally the mosquitoes, which are soundless and enormous here, made conversation too great a sacrifice forcomfort. I helped the colonel drape himself, like a sheeted ghost, in a great swathe of netting. Then he stretchedout on the sofa, and I went up to my room to write by the dim little electric light that shines through my thicknetting like a feeble moon through a mist. I was just getting into bed when I heard Colonel Robert's voice,very low, at the stair landing: "The boys have just decoded a signal. The Japs have attacked Ceylon, and bombed some places in India.""What places?""We can't get the names straight. Our signals are coming in garbled and scrambled again... Goodnight."

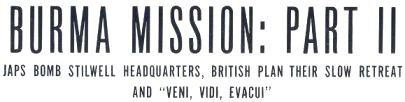

Up the steps of headquarters runs General Stilwell to keep appointments for interview with Clare Boothe at 5:01 p.m.Captain Frederick L. Eldridge smiles in the background. Up the steps of headquarters runs General Stilwell to keep appointments for interview with Clare Boothe at 5:01 p.m.Captain Frederick L. Eldridge smiles in the background. |

Today I determined I wouldn't talk about anything, or anybody, but Uncle Joe Stilwell.Make Uncle Joe talk to me about himself for an hour. His aide, Lieutenant Dick Young, says, "You must havenoticed that the General is a very taciturn man." I hadn't noticed that. He talks quite a lot, really. But asProfessor Roberts put it, "Words, sez nuthin'." Stilwell is not a silent man, but he is, I've noticed, anuncommunicative one. Anyway, I laid in wait for him at the mission door this morning after breakfast, and caughthim going out to the pow-wows. Looking about as happy as though I had asked him to give me his right eye, he atlength promised to give me, alone and uninterrupted, the hour between 5 and 6.

At five minutes to 5 I went downstairs. At about two seconds past 5 General Stilwell's car came into the drive.He laughed as he saw me standing in the door with note pad ready. "All right, all right," he said, "Let's get itover..."

We went inside and he ordered a cup of tea, and sat very stiffly with it in a big comfortable chair. I said,"Can I take a picture of you first, drinking your tea?" He put the cup down quickly. "You'll never get a pictureof me at any front drinking any cup of tea," he said, "Just as soon be caught by the readers back home taking aswig out of a rum bottle!" He seemed to think that the U.S. Grant habit, while dangerous, was not nearly sodevastating to an American soldier's reputation as tea-drinking.

There are certain major points of difference between Stilwell's officers account of his times and characterand his own. On the facts they all agree but not on the interpretation of the facts.For instance, Dorn, Young, Roberts and Captain Eldridge, a Mid-western ex-newspaper man who is press liaisonofficer here, differ with Stilwell completely as to why he ever became a soldier. They say, "From boyhoodyoung Joseph Stilwell showed a marked preference for the military life, and although his father, Benjamin Stilwell,was a doctor and a lawyer, and although his brother went to Yale, he insisted on going to West Point."

Stilwell's own account shows no such "marked preference for the military." He says his entrance into West Pointwas a result of a "most unfortunate incident," when, as a high school boy in Yonkers, he became embroiled in afracas, following a basketball game. The fracas began with the stealing of some ice cream in the assembly hallduring the dance, and wound up in a free-for-all fight "in which somebody socked the Principal." He says theice cream stealing was a "little idea we kids all thought up together" but wasn't quite clear who it was thatsocked the principal, except "there were so many of us tangled up, I certainly can't take the credit." In anycase, the story made the New York newspapers, and young Joe was in considerable disgrace with both Stilwellpere and Stilwell mere. Whereupon his Dad had him on the mat, informed him he had been a "fresh kid" for toolong, and that Yale - upon which he had set his heart - was a far too liberal and undisciplined an atmospherefor one of his obstreperous nature. Old Eli, said Stilwell pere was better suited to the temperament of hisyounger brother (John Stilwell, now Vice President of New York's Consolidated Edison Co.). "From there on,"said Uncle Joe, "I found myself gently but firmly steered into West Point."

When I asked him from whom he inherited his obstreperousness he said, "I come of very peaceful folk. I attribute it entirely to prenatal influence." He said that although his mother and father were nativeNew Yorkers, he had been born in Palatka, Fla., 59 years ago on a little orange grove the family rentedone winter. But, it seems, the peaceful orange grove that was the scene of his birth was set on a piece of land called "The Devil's Elbow," and Uncle Joe said, "I've somehow never gotten out of the Old Boy's crook since."

Stilwell first went to China in 1920. A military language student in Peking, he studied and then served thereuntil 1923. After that he was an executive officer of U.S. forces in China stationed at Tientsin from 1926to 1929. From 1935 to 1939 he was military attach to the Gissimo's government. But as to why Stilwell went toChina in the first place, he and his officers also disagree. Roberts said, "because he had always had a profound interest in Oriental languages and Chinese culture and art and military sciences, and that whenWorld War I was over he had requested a post which would allow him fully to develop his cultural bent."

Stilwell's version is totally different. He said that when he returned home from France in 1919, he found "a wave of pacifism was already in the making... I went right into Chauncey Fenton's office, then head of theWar Personnel Department in Washington, and I said, 'Chauncey, from here out the Army is in for a terrible drubbing at the hands of the sob sisters and starry-eyed idealists who think human beings ain't. I can't stayhere and watch this country disarm and demobilize to the point of disaster. It'll just make me boiling mad,and I'll do or say something that will get me into trouble. So please give me a job that will remove me as farfrom this painful scene as possible.'"

Fenton told him of an arrangement whereby the University of California would give language courses to officerswho would then proceed to the Far East. "Do you know anything about China and the Chinese?" Fenton asked,"Nope," Stilwell said, I don't, but I'm a candidate for learning." One hour later he had gotten his writtenorders out of Fenton. After a year at the California language school, he sailed for the Far East. It was perfectly true, he said, once in China he had become deeply interested in Chinese literature and the classics,but this was a result and not the cause of his going to China.

His Chinese friends don't call him Stilwell, he says. Long ago they gave him a Chinese name: Shih Ti-wei, themeaning of which is, prophetically enough, "One who makes important history." He says he has many good friendin America, too, but few of them are in Washington. "I never knew a Senator well enough to call him by his firstname," he says.

His officers tend to believe that Stilwell is a very modest and retiring fellow who loathes publicity and has

Stilwell's name in Chinese characters is drawn by Colonel Frank Dorn who speaks Chinese as well as General Stilwell.Dorn, an artist, drew Stilwell's campaign maps. Stilwell's name in Chinese characters is drawn by Colonel Frank Dorn who speaks Chinese as well as General Stilwell.Dorn, an artist, drew Stilwell's campaign maps. |

And Roberts, who ought to be a judge of these matters, claims that Uncle Joe makes magnificently pithy and witty speeches when the occasion requires. Uncle Joe says: "Oh, I can stammer through the usual platitudesbefore civilians. But I never found it necessary to use more than half a dozen words to soldiers. All I'veever said is 'Boys, get in there and fight.'"

His popularity with his men and his officers is based on a fine mixture of his extraordinary consideration ofthem, his lack of brass-hat pomp, and his tough insistence that his orders be obeyed instantly and with themaximum efficiency. Pinkie Dorn, who was with him on maneuvers in California and Washington in 1941, saidStilwell slept on the ground with his men and personally observed every front-line emplacement.

Dorn says he got his now-almost-forgotten nickname, "Vinegar Joe," when he was teaching tactical maneuversat the Infantry School at Fort Benning. "His remarks," Pinkie said, "when he has to do with dopes, sometimes have a pretty high acid content." All his officers here marvel at the way the vinegar in Uncle Joe has tendedto disappear. They say he bends over backward to avoid conflict, verbal or otherwise, between members of thejoint Allied staffs. Pinkie says "Burma Balm Joe" would be a better nickname for him now.

Hard as it is to get the General on the subject of himself, it is harder still to keep him off the subject of his family. He is enormously proud of his wife, who he says is a better soldier than he is, and his fivechildren: two sons - one in the Army - and three daughters, one who plays Chinese stringed instruments, anotherwho paints so well "in the Chinese manner" that she has even given exhibitions. But he only spoke briefly of theStilwell family itself - which settled on Staten Island in 1632. "There's still a Stilwell Avenue in Brooklyn."And of a forebear called Nicholas Stilwell, who owned most of Staten Island once, and had a farm on New York'sEast Side. A man, Uncle Joe concluded, of remarkably poor vision, since he somehow managed to lose these properties.

It seems that 140-lb. Uncle Joe hasn't "changed a pound since I entered the Point." he swears he was never anathlete, though he played football at the Point, basket and baseball, and was "a very minor track star.""But," says Dorn, "he can walk the shoe leather off any soldier living. In view," says Dorn lugubriously, "of the transportation problem in Burma today, make a note of that. It may be important."

When I asked General Stilwell why he has voluntarily given up his safe American command to take "such a pineapple,"he answered, with his funny little chuckle, "It seemed then like a chance worth taking. And it seems now I was right. Every hour that Burma holds, saves America an hour in Australia and the Philippines."

Before bombing of Maymyo, Captain Fullerton, Colonels Roberts and Dorn laugh at themselves posing with tommy guns in the green and pleasant glade outside General Stilwell's headquarters. Before bombing of Maymyo, Captain Fullerton, Colonels Roberts and Dorn laugh at themselves posing with tommy guns in the green and pleasant glade outside General Stilwell's headquarters. |

Maymyo, Wednesday, April 8

I was in my room writing in my journal when the thin frail note of a siren cut across the cool perfumed air.I began to gather up my papers and put the lid on my typewriter when General "Long Tom" Hearn's massive figureappear in the door. "We go out to the slit trenches in the compound," he said almost apologetically."How much time have we?" "I don't know," he said. "We've had several alarms. We've never really had a raid.But don't fiddle," he added, as I sat down to load my camera. Then he lumbered leisurely off down the stairs.

The mission servants were already huddled in their trenches when, in twos and threes, the American officersbegan to gather in the little woods where the slit trenches are. They were all there except General Stilwelland Lieutenant Young who had gone off again to see the Gissimo. They had tommy guns, pistols, cameras andhelmets. After ten minutes or so passed, they began to play and pose with the guns, snapping pictures ofone another. Then they took off the heavy helmets and lit cigarets, and sprawled on the woody ground, laughingand joking. And everybody kept saying to everybody else: "We've had several alarms but we've never really hada raid." "What are the odds we'll have one today?" I asked Colonel Roberts, who had been sitting silently onthe edge of his trench.

He paused as a truck went by in the distance, lifting his head swiftly to define the motor sound. "A real raid?A hundred to one-on," he said emphatically. "Why? Because the Japs have Burma honeycombed with spies.By this time they must know the two most important military objectives in the Far East are in Maymyo.""American and British headquarters?" He laughed derisively, "The Gissimo and Madame Chiang. Knock themout and 'Chinese resistance' becomes - unpredictable." "Long Tom" Hearn stolidly finishes his pipe waiting for bombers, while Colonel Benjamin G. Ferris works on a map of Burma.Bombing did not faze either of these veterans.

"Long Tom" Hearn stolidly finishes his pipe waiting for bombers, while Colonel Benjamin G. Ferris works on a map of Burma.Bombing did not faze either of these veterans.

Now he kept his face turned to the sky. He was straining, straining his ears. Then he said: "You'll have toforgive me, I'm nervous. I don't like being bombed or shelled. Had quite a lot of it in Hankow and Nanking.And on the Panay."

He nodded toward a group of laughing officers that were taking pictures of one another, pointing tommy gunsat the sky, in fierce attitudes. "Look at them now," he said, "then see how they behave when its over. Itwill be quite interesting for you." I nodded toward Long Tom who was sitting against a tree, thoughtfullysucking his pipe. The colonel said: "He'll let his pipe go out. Otherwise he won't change." And then,quite suddenly, he rose and said, "Down in, they're coming."

Then we heard it, the unmistakable thrum, thrum, thrum of many engines. For a moment everybody froze

in the position in which the sudden awareness had caught him. General Hearn knocked out his pipe on the soleof his enormous foot, and slowly rose and ambled into his trench. One by one the officers disappeared belowground. A young major suddenly appeared, leaning into my slit trench. He thrust his helmet toward me and said,very gallantly and a little breathlessly, "Here, put this on your head!" I said, "Thank you," and took it,and put it on the ground, and sat on it, next to Frank Roberts. I knew that the helmet was only good for that.A direct hit, and it was no use. Otherwise the sides of the trench should protect us. Thrum, thrum of approaching Jap bombers sends Americans into trenches and shelters.Notice parked trucks that Colonel Roberts said should have been dispersed under cover before bombing.

Thrum, thrum of approaching Jap bombers sends Americans into trenches and shelters.Notice parked trucks that Colonel Roberts said should have been dispersed under cover before bombing.

The thrum, thrum, thrum was growing very loud. There were plenty of them. Frank Roberts began to swearsuddenly, "We're damned fools. We never learn except by experience, and until it's too late." "What's thematter?" "Look at those trucks and jeeps parked thick all around the headquarters, and Dr. Seagrave'sambulance! We should have dispersed them. Well, tomorrow we will. And tomorrow we won't feel like bloodyfools about bringing our kits and typewriters and briefcases. If there is a tomorrow."

He pointed to a blue patch of sky between the trees. Like little white birds against the brilliant blue sky,flying in perfect formation, high up, were the Jap bombers. "There! There! 8, 12, 16, 20, 28 of them. They'reright overhead now. Here it comes!"

There was a long, long whine like the whistle of an onrushing train in an interminable tunnel. I closed myeyes and dug my chin into my breast, hunching my shoulders about my ears, as shuddering blast after blasttore the earth and air and woods all about us. An then the thrum, thrum, thrum faded and there wasan awful silence.

My insides had not stopped quivering, but my hands had, when we came out of the trench on the all-clear.The colonel was right. The officers who had had their first baptism by bomb were quite different men now.They were smiling, yes. They kidded a bit, yes. But they were not really gay anymore and, as you looked fromone face to another, you saw that they knew at last that they lived in a world where men were mortal.Until you've heard death stream in shell or bomb through the insensible air, impersonally seeking you outpersonally, you never quite believe that you are mortal. As we walked back through the woods to the untouchedheadquarters, one of the officers said with a sudden wondering humility, "Think of the English peopletaking that hour after hour - night after night - for a whole year.

I saw the young major who had given me his helmet, and as I handed it back to him he said suddenly, "Listen:I'll feel better if I tell you this; you know what I thought when I heard that first bomb scream? Well-,"he blushed, "I thought... why the hell did I give her my helmet?" I said, "It took courage for youto admit that." And he said, "Well, sure. But look, the point is they may come back." He held out his helmet,"So please keep it." He took a deep breath and then he smiled.

Bomb shelter caves in under Jap bombing, burying two Burmese and a white woman.Here Dr. Williams helps out a shaken Burmese while Captain Eldridge takes pictures. Bomb shelter caves in under Jap bombing, burying two Burmese and a white woman.Here Dr. Williams helps out a shaken Burmese while Captain Eldridge takes pictures. |

Now the roads were full of stampeding horses and cattle and natives carrying bundles, suitcases. As we passeddown the street, everywhere coming out of the flimsy houses, with their windows shattered, porches and roofsstove-in from the bombs that had fallen near or on them, we saw the little people of Maymyo, loading theirbullock carts, ghatties, bicycles, for the long exodus. George Rodger, the LIFE photographer, came along inhis jeep. Half the town, he said, was already "on the march to India." There wasn't "much damage" done - not,anyway, compared to Mandalay - only about 80 causalities, a hit on the hospital, and on a trench with a lotof children in it. The soldiers and fire force and Red Cross had everything well in hand. "Pattern bombing,"Colonel Roberts said, "They were plastering the residential section, hoping to get the Gissimo." Rodger said,"And?" Roberts shook his head. "I checked that the first five minutes. Nearest bomb to Uncle Joe and theGissimo was 50 yards."

We went back to the mission because somebody said it was lunch time. I had a luncheon engagement with GeneralSir Harold Alexander, but in the excitement I quite forgot about it. I went up to my room to change my slackswhich were covered with the mud from the slit trench. That was the first time I realized how I had burrowedanimal-like against the trench's muddy side. The window panes were in small pieces. The one electric-lightbracket had fallen off the wall and the pictures of the Alps were ripped crazily. Everything was coveredwith bits of plaster.

The servants have all gone. Only the cook and the white mission caretaker have stayed. The officers went into the kitchen themselves and got the food, and the lieutenants and captains served the majors and the colonels.Roberts said, "This, gentlemen, will be our last formal luncheon in headquarters. Tomorrow we'll takepicnic lunches to the woods."

I was right in the middle of lunch when General Alexander's aide, a smart, smiling, tall young man, arrived totake me to "Flag House." I was very embarrassed. I said, which was true, that the telephones had gone out oforder and, besides, I had assumed that bombings canceled invitations - particularly when headquarters are thetarget. The A.D.C. said pleasantly, "Oh, not at all. Unless the target is definitely achieved."

General Alexander's house is farther out of town than the U.S. mission. It is set on top of a grassy knollin a lovely garden full of larkspur and roses. Either because of its remoteness or the fact, as it later developed, that General Alexander had refused even to go into his slit trench, the servants had not left.A handsomely-turbaned Indian "bearer" met me at the door. General Sir Harold Alexander and a brigadier wereon the terrace. General Alexander was a small, handsome, vigorous and charming man. He wore the pale robin'segg blue flannel bush jacket that many Indian officers wear. It brought out the steely color of his clearEnglish eyes. The brigadier was tall, correct and stalwart, though he had a small moustache which he constantlybut cautiously stroked, as though it were a feline pet which might suddenly strike back at him. They weredrinking pink gins (gin with lime and maraschino). "Everything all right your way?" the General asked in hislovely British voice. "Oh, yes." We do not again refer to the bombing of Maymyo.

The table was set with real silver and a well-arranged bowl of flowers. The food was much better than at themission, and so was the conversation. We talked of many things before we came to talk of the Battle of Burma- the evacuation of Dunkirk, in which Alexander had played a gallant part; the Battle of Britain and theblitz in London, which he had lived through daily; the Libyan front, about which he felt most confident;and the Russian front about which he was wholly sanguine. It almost seemed rudely irrelevant to mentionBurma. But finally it came up inescapably in the course of conversation. General Alexander did not beatabout the bush for a single second.

"We will hold Burma as long as we can," he said quietly. "I am utterly determined we will not retreat onestep faster than necessary. Guts and determination are what are going to win this war. We can and we willfight as hard a delaying action in Burma, as your MacArthur fought in the Philippines. What MacArthur did,we can do, though our circumstances are a great deal more difficult."

Then he sketched quickly, vividly, convincingly some of those circumstances: troops, hardly more than 7,000,who had been in the line three and a half months unrelieved, with no air protection at all - the A.V.G.,under Chinese operational command, were naturally protecting the Chinese front; the almost total lack ofsupplies, since it was impossible to send them from India, and what there were on hand had to be shared withthe Chinese in the Sittang Valley. (He said 100 American transport planes would entirely change his supplyproblem.) The British forces were mechanized and therefore had to travel down the one and only main highwaythat traverses the Irrawaddy, where they were constantly subjected to Jap strafing from the air, and beingwaylaid and ambushed by Jap units on foot that percolated and infiltrated along the jungle roads, layingobstructions which trapped tanks, trucks, all vehicles chained by their own treads and wheels to the openhighway. The 100 tanks we brought to Burma have been almost useless here. "I'm getting my units into nativetransportation as rapidly as possible," he said, "bullock carts, gharries, on foot, elephants, if we can getthem - that's the way we'll have to fight the Jap in the jungle. That was the lesson we learned in Malaysia.And we're arming the Chin mountaineers, too, for guerrilla warfare. They've always hated the Burmese - they'llgo after the Burmese wherever he's fighting with the Japs. The Japs are nearing the oil fields now, butwe're fully prepared to destroy the fields, blow up the installations, scorch the earth behind us."

I asked him: "But if the Japs reach Mandalay and Lashio, where they'll control all the airports left in northBurma - Shewbo, Bhamo, Myitkyina, Loiwang - then what?" General Alexander said, "Then British forces willretire into the Chindwin Valley, re-form along the Indian frontier and wage a guerrilla war in the mountains."

"That really means that Burma would be gone. Aid to China would become immeasurably difficult. A great air effortwould have to be made out of India, a naval effort in the Bay of Bengal to dislodge the Japs. Well, how are we then going to lick the Japs in this part of the world?"

He said, "You always forget, people who are not militarists always forget, that Japs have their troubles, too. Their lines are very overextended. Right? We are falling back on a fairly strong arsenal, India. Right?The Japs have suffered a great loss in planes. Their capacity to replace cannot match ours. Right? The monsoonseason is coming on. It will be difficult for them to operate."

I said, "But they do keep coming on in spite of overextended lines. And if the monsoon makes it hard forthem to get at us, it will make it hard for us to get at them - if, by the time the season begins, they are

Photographer Rodger was behind his jeep's windshield when the last bullet of the battle of Shwegyin hit and shattered the glass.In thick of fighting, he never saw a Jap. Photographer Rodger was behind his jeep's windshield when the last bullet of the battle of Shwegyin hit and shattered the glass.In thick of fighting, he never saw a Jap. |

Now General Alexander looked at me with his keen, honest blue eyes blazing faintly, and he said evenly:"It is important to hold here as long as possible because it gives India a chance to prepare.It is more important to hold India, even, than Burma. But, after all, what happens out here is onlysecondarily important. What is really vital is what happens in Europe. We have only so much airpowerand manpower now, today, and we've got to beat the Hun first. He's the real enemy. Never forget that.But when the Hun is licked, Japan - however far she has spread through the Pacific or in Asia, even ifshe takes India - can never hold her gains. When Germany is crushed, America can then turn loose everythingshe has in the Pacific on Japan. And we can send everything we have from the Near East. Russia will then befree to attack from Siberia. And all the little Jap's gains will be quickly disgorged. This is a certainty."

I thought, "Where a soldier's heart is, there is his battlefront also." Alexander's heart, bitter with thevengeance he had brought off Dunkirk, lay not in the Burmese jungle fronts of Empire but on the WhiteCliffs of Dover.

I played the devil's advocate. I suggested that perhaps the Chinese might have a different point of viewabout the relative importance of the Asiatic, and European theaters of war and that, with Burma closed, theymight, either in a wave of despair or because of Japanese military pressure on all their fronts, ceasefurther resistance. "That," General Alexander said, "would certainly be a tragedy for them if it could notbe avoided, but a grave error of judgment if it could. For in the end we must win - when the Germansare beaten - and our Chinese allies will sit more happily and profitably at the peace table - if they do goon resisting."

I left Flag House in a very mixed state of emotions. It seemed more certain than ever Burma was finished.Every word Alexander had said was a dreary nail in its coffin. And yet - and yet - if he were right, if hewere truly right, that the loss of this front which in a war of unlimited demands and only limited menand material was inevitably secondary, this was no matter for despair, then why feel so despairing? Is itbecause the stink of Mandalay, entering my civilized nostrils, has permeated every cell of my mind, cloudingit with false intimations of inevitable disaster, corrupting, in short, my untried American valiance?

When I returned to headquarters the officers had finished dinner. Headquarters was having an involuntaryblackout. A bomb had put the local powerhouse out of commission. It had been a lean and meatless meal bycandlelight. Tonight not even boiled strawberries. The quartermaster had gone to the market place an houror two after the bombing. But even by that time "everything was gone," except several bushels of enormous cabbages which he had bought up instantly. "From here out something tells me we're going to have cabbagethree times a day, and very little else," somebody said. "Too bad we can't slaughter some meat, againstthe bad days. But there's no refrigeration."

We sat in the living room in a great circle and then somebody went to the piano and began to thrum itsyellow, dented, tuneless keys. And presently they were all singing in the candle light... "Iss-sa longa,longa tray-ull a-wind-ing into tha lan duve mi dreeems..." "My barn-nie lizezova the O-shun... Oh, bring.. ga back my barrrn-nie to me..." - all the old dearsongs that kids in school, boys in college and men in camps have sung since this brave new 20th Centurydawned on the backward Victorian Era. They sang warmly with lusty, uninhibited voices. And finally theyassembled that ancient, classical male quarter which rendered with full feeling - "Sweeee-dadaline-my adda-line... inawe miiii dreems-yaw fairfaze beems-yawr tha' flah-wer ohmii art...

Thursday, April 9

This morning when the alert sounded, everything was organized quite differently. Cars and trucks were promptlylined up in the mission driveway. The officers piled in with their briefcases and papers, typewriters andessential duffels. The servants who have remained after yesterday were put in a separate truck under a Chinesesergeant. Our caravan drove into the nearby woods where it parked in the dense shrubbery. The all-clear did notcome for two hours.

The choice for the rendezvous of our caravan had been well made strategically. But it turned out it was somethingless than a happy place to be. The night before, the natives had dumped several horses killed in yesterday'sbombings, near at hand. They were very ripe already. So several of the officers and I walked up to the top ofthe hill. It commanded a fine view of Maymyo and the forest around.

Colonel Roberts had a map. It was the same map of the world he had marked and studied so carefully on the Clipper.He spread it out on the woodsy mold under a tamarisk tree and we all stood around and looked at it verysolemnly, saying nothing much or saying all the same old things about shipping, and "if the Ruskies hold" and"if India holds" and "if the Japs can't join up with the Germans in the Indian Ocean" and "if Australia holds"and so on.

Someone said, "Well, I damned if I know." Someone said, "Air. Air." The all-clear sounded and I was spared thisday the old, old argument of the ground officers, as to whether "air could do it alone."For dinner we had potatoes and cabbage.

After dinner tough Jack Belden, the Time and LIFE correspondent, lean and elegant George Rodger and gay,bouncing, resilient Berrigan, the United Press man, came in a jeep and took me to the Maymyo Country Club.The club was full of young British officers and there was a handful of pretty girls. Belden and Berrigan andRodger all said they wished they could get out of Burma. It had becomes, they said, impossible to file dispatches. At Mandalay the last cable in Burma had been destroyed. Copy now had to be sent by hand to Lashio,put on a plane for either Chungking or Calcutta, where it had to be censored first by British or Chinese censors.Berrigan said that after jeeping from the from to Maymyo, which sometimes took two or three days, you often hadto rest up a day before you were in shape to write a story. He said he'd bet it was often two weeks after he'd

Correspondent Jack Belden grins at wheel of his own jeep in which he raced up and down Burma.He finally hiked out of Burma with General Stilwell's evacuation party. Correspondent Jack Belden grins at wheel of his own jeep in which he raced up and down Burma.He finally hiked out of Burma with General Stilwell's evacuation party. |

And, Belden said, even the stories that did appear probably had the "hell cut out of them" by the censor. War,he said, is hell for a correspondent, when your side is losing. You can't say how badly you're losingbecause that just depresses everybody and you can't tell why you're losing because that's either comfort or information to the enemy. All you can do is wait until the whole thing is lost and then you fileone big exciting story on the blowup, and then go to some other front. They thought Burma was being lost,not in the Sittang and Irrawaddy valleys but in New Delhi, London and Washington. Burma, they felt, was theresult of inertia in India, obstinacy in England, ignorance in America.

Then they began to tell stories of the front, which were so exciting and bloody and terrifying and beautifulthat I didn't get bored until midnight. Then Berrigan and Belden said, "We're going down tomorrow, we'll takeyou. You ought to see the front." And I said, "General Alexander offered to take me this morning. But withthings going the way they are, we'd probably get blocked off by the Japs somewhere. We'd get out, but myfeet would swell from walking, my lips crack with the sun, I'd get fatigued, and in the end you'd curse meand say 'why the hell did we bring a woman?' And whenever such bitter recriminations can be avoided, it isbetter for a woman to avoid them."

I asked Belden what he thought of the American mission. He said, "God, they're good eggs! And Stilwell's a honey!Wouldn't it be fun to see them leading American doughboys?" He said the most serious thing about the Chinesearmies, nobody talked about: China had long imported rice from Indo-China, Siam and Thailand for the troops inYunnan. And if that rice goes - and the oil - their only available source in Asia, he thought they'd have a badtime of it. He said, "God, they are an ill-equipped bunch, but if you wanted to feel your heart turn over withexultant thrill, you ought to hear them charge into the field, yelling their exultant battle cry - 'Chung KuoWan Wan Sui!' - that and the Marseillaise and Scotch bagpipes. What is our equivalent?"

To Lashio, Friday, April 10

Late this morning, with Colonel Roberts and two other officers who were hoping to get to Chungking, I took theroad back to Lashio. We were late getting off because there was a two-hour air raid, so the whole trip was madein the blistering heat of high day.

At five o'clock we came to the outskirts of Lashio and went on to Colonel Boatner's little three-room cottage.Boatner knew nothing about plane movements. "It wouldn't surprise me a bit," he said cheerfully, "if the Japstook our Lashio field tomorrow."

The telephone rang and Boatner yelled, " A CNAC plane headed for Chungking has just landed! It's taking off in30 minutes!" I said, "I'll take it, " Boatner said "your ticket reads 'to Calcutta.'" I said, "I'm either goingto Chungking tonight, or I'm going back to Maymyo. I'll stick with either Stilwell or the Gissimo." Robertssaid, "you're going to Chungking." We threw my baggage into the car and drove out to the airfield. "Dude Hennick" (real name: Frank L. Higgs), whose letters home inspired "Terry and the Pirates," poses with automatics beside the Douglas transport he flew into China.

"Dude Hennick" (real name: Frank L. Higgs), whose letters home inspired "Terry and the Pirates," poses with automatics beside the Douglas transport he flew into China.

The CNAC pilot had gone into the operations building while the plane was being unloaded. When I found him, hewas an American with a handsome, dark face, slick black hair underlined by black eyebrows that made one straightline over his heavily lashed eyes. He was a character famous to millions of Americans - Dude Hennick of "Terryand the Pirates" fame. His real name is Higgs and his letters out of China to an old friend, Milt Caniff, thecomic-strip artist, had inspired many of the adventures of the Dragon Lady and Burma.

I said, "Hello Dude, my name's Burma Boothe and I'm a lady in distress which, I gather, is your specialty."And he said, "Well, beautiful, if you're in distress, it's probably your own damn fault for being in China.What am I supposed to do?"

"Take me to Chungking - it's the only way I can get out of here. And then from Chungking bring me back toCalcutta." He said, "Have you got a ticket on this plane?" And I said, "Obviously not or I wouldn't be indistress, would I?"

Presently the engines of the plane began to turn over. Roberts said, "You're off." The passengers were allChinese civilians and most of them had babies. I lingered on the steps until the last minute. Then Robertssaid, "Goodby. You've got your story. And tell them the truth. The American people want to know. They've gotthe right, haven't they?"

"Oh, yes," Boatner said, "The story? If you know the story, tell me in three words, I'd like to know, too."I got in the plane. "In three words? 'Veni, Vidi, Evacui' - which means, we came, we saw, we got thehell out, Colonel." "I thinks she's got the story," Boatner said cheerfully.

As we taxied off, I pressed my flashlight three times against the windowpane and Colonel Roberts answered withthree small sharp flashes from his own.

|

|

Adapted by Carl W. Weidenburner from the June 15 and 22, 1942 issues of LIFE. Portions copyright 1942 Time Inc.

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE PART ONE PART TWO ABOUT THIS PAGE CLOSE THIS WINDOW