|

|

Though in action just six months, the famous Flying Tigers racked up an incredible record against the militarily superior Japanese in one of the most heroic sagas in aviation history. by Roy Grinnell |

|

While Americans at home, still numb from the horror of Pearl Harbor, were trying to have a normal Christmas, a small band of other Americans far across the Pacific were fighting desperately to stave off a massive Japanese air attack on the vital seaport city of Rangoon in Burma. Sweltering, smoldering Rangoon, hub of England's empire in Southeast Asia, had been the target of a paralyzing Japanese bombing raid only two days earlier on Dec. 23. Smoke still swirled from burning docks and gutted buildings, and thousands of homeless refugees choked debris-clogged streets, bringing the city to a standstill. A second attack could devastate the seaport completely, in the process wiping out the now famous Flying Tigers.

The pilots, while well-trained and dedicated, lacked combat experience. Their already outmoded P-40 Warhawks were no match for the new lighter, more maneuverable Japanese Zeros. Though the group supposedly consisted of 100 planes, scarcely more than half that number were ever operational at any one time, and these were patchworks of crude, makeshift repairs. Poor food, primitive living conditions, disease, insects and brutal heat all helped to sap the men's fighting strength.

That such a ragtag force could accomplish anything is amazing - that it could achieve such phenomenal success over the militarily superior Japanese is little short of a miracle. Because the Tigers' exploits were so spectacular and their fame so widespread, many even today are not aware that they were in action for only a relatively brief period - just a little over six months from Dec. 20, 1941 to July 5, 1942.

|

The Tigers were divided into three squadrons - the First, nicknamed "Adam and Eve"; the Second, called "Panda Bears"; and the Third, "Hell's Angels." The First and Second Squadrons were sent to Kunming, China. The Third, the Angels, was based at Mingaladon Airfield near Rangoon, with a small contingent of British RAF flying Brewster Buffalos.

Out on the airstrip at Mingaladon early that Christmas stood 12 AVG pilots on alert, peering anxiously into the bright morning sky. They had overheard on a radio broadcast from Bangkok that the Japanese were coming to deliver the final death blow to Rangoon, and they tensely awaited the alarm that would send them running for their shark-mouth aircraft. Minutes dragged as 0900 came and passed with no sign of the enemy. The men were growing nervous. Squadron Leader Arvid Olson, squinting into the glaring sun, revealed to Flight Leader Robert Smith how fearful he was of being taken by surprise.

Hunch Pays Off

Finally, at 0930, Olson decided to send up three P-40s to scout to the east. His hunch paid off. At 0950, George McMillan, flying lead position, radioed back that he had sighted a large formation of Japanese bombers coming in over the Gulf of Martaban, about 60 miles out. He stated quite loudly that the rest had better get their tails up there fast.

Taking off in twos, roaring down the single usable runway, the remaining P-40s raced to McMillan's aid. When they caught up, they were stunned by what they saw. Stretching to the horizon was a mighty air armada of some 70 Nakajima Ki-21 bombers (Sallys) and about 30 fighters - 12 obsolete P-40s against 100 of Japan's best.

In the words of Flight Leader Smith, "We climbed as quickly as possible, checking gun switches and sights, then from about 1000 feet above made a diving turn toward the enemy formation. We each picked out and individual bomber and dove on it, ready to open fire at 300 to 400 yards. I had learned from the previous battle on the 23rd that it's practically impossible to score a hit with deflection shots from an angle unless you've had considerable aerial gunnery training. I had none. Hitting a moving target is greatly simplified if you eliminate the deflection problem, but this meant boring in from dead astern and firing at point blank range. While the method worked, it was also a lot more dangerous since all those guns firing back at you had no problem of deflection shooting either.

"After the initial pass, it was every man for himself. Within 10 minutes, each of us had scored a hit or two, and the sky was filled with flaming, smoking bombers, twisting down toward the rice paddies below. I blasted two bombers, one exploding directly in front of me and the other going down out of control with an engine blazing.

|

|

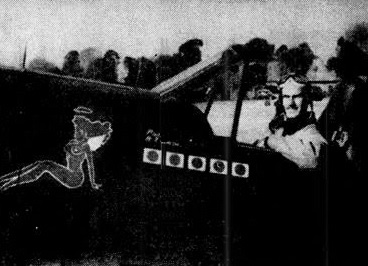

Nostalgic memories are caught in old photos, most never before published. Top left: Postwar reunion shows Chennault (middle) with ex-Tigers. Flight Leader Robert T. Smith, a hero of the Christmas Day battle, stands to left of Chennault. Bottom left: In rare moment of relaxation, Chennault at bat plays ball with his men. Top right: AVG airmen pose with one of their famed Warhawks. Center right: R. T. Smith was one of the first to gain "ace" status with five kills, as indicated by decals on his fuselage. Bottom right: A P-40 gets a tooth check as pilots await orders to scramble.

There was no turning with the fighters in the classic dogfight tradition, as we knew they could outturn us. However, we could outdive them and get away if one got on our tail. Also, our P-40s were more rugged with armor plating to protect the pilot and self-sealing fuel tanks. The Japanese had neither of these and could not withstand much machine gun fire.

Close shave with a Zero

"On my last pass at the bombers one of my wing guns was hit in the electrical solenoid and continued to fire merrily away until all the ammo was expended. Then I saw him - a Zero coming straight at me head-on. We each opened fire at about 400 yards. I could see the winking flashes from the muzzles of his guns. At our closing rate of about 600 mph, we only had a few seconds. I held my gunsight pipper directly on his prop hub and blasted away with all five guns, wishing the sixth hadn't been put out of use. He took no evasive action, and for a terrifying moment I thought we were sure to collide. Then miraculously he passed below me, our prop tips missing by bare inches. I immediately felt the turbulent wake of his prop wash and whipped into as tight a turn as I could without blacking out, certain he'd be on my tail. But I was lucky. Off in the distance, he was rolling lazily into a shallow dive, going down like a flaming Roman candle.

"By now the scattered enemy forces had turned tail and were limping back home to the east. A few of us continued to chase them far out into the Gulf of Martaban, but this was not a habit-forming practice as we were not equipped with survival gear for ditching at sea, and the gulf was notorious for the size and number of sharks it contained.

"Out of ammo, I now faced the prospect of getting back myself - not a happy one as home was still 50 or 60 miles away. My own plane had been hit many times, but in the heat of battle I hadn't been aware of it before. I was relieved to spot another P-40 headed my way. It was Bill Reed, wagging his wings and wanting to join up with me. What a welcome sight Bill was!

"We headed back to Mingaladon together and circled the field to see what shape it was in. The runway was pocked with bomb craters, especially along a third of its length at the upwind end, cutting short our landing distance. It would be close. A P-40 was upended in one crater - someone hadn't quite made it. We roared over the field low, did our victory rolls, then peeled off, got our gear down and managed to come in safely. Only then did I realize how really lucky I had been. One bullet had gone through a prop blade, fortunately in the thick part near the hub or it might have caused the prop to shatter. The resulting vibration would have ripped the engine from its mounts and possibly torn the entire plane to pieces."

Everyone was lucky that day. Of the 12 pilots sent up, all returned. Two - George McMillan and Ed Overend - were shot down, but succeeded in crash-landing without injury. Another, Parker Dupuoy, sheared off part of a wing in a mid-air collision with a Zero, yet skillfully managed to get his crippled P-40 down without mishap. Everyone in the group had scored at least one kill. Flight Leader Smith was one of several with three, which, together with two from the previous battle of the 23rd, made him one of the first AVG aces with five credited kills.

While the Tigers would fight on to other victories, none would equal the record achievement of that one Christmas Day - 28 downed enemy aircraft without a single loss of life. The RAF, engaging another formation of 30 Sally bombers, added eight more kills to the tally, bringing the total to 36 - approximately a third of the entire enemy force.

Downed 286 enemy planes

In all, over the short six-month period they were in action, the Tigers are officially credited with destroying 286 enemy planes and 1500 Japanese. Unofficially, the actual toll is believed closer to 600 planes. Against this, the AVG lost 13 men in combat. On July 5, 1942, the Tigers were officially disbanded to be replaced by the newly formed 23rd Fighter Group of the U.S. Army Air Corps.

Although early in the war, the Tigers' feat was to rank in importance with the later Battle of Britain and the naval air victories at Midway as a major turning point in the conflict. Much of the credit must go to the brilliant leadership of the group's commander, General Chennault. Inventive and unorthodox, he was a master at improvising methods of combating the superior Japanese. Recognizing that the heavy P-40s were outclassed by the lighter Japanese fighters, he developed special tactics for taking advantage of their greater weight and diving speed: Get above, dive, try to score a hit on the first pass, then continue diving and gain altitude again for another pass.

How Tigers got their name

Exactly how the Tigers got their name and shark-mouth decoration is still in some doubt. Most experts agree, however, that the shark mouth was adopted by the AVG partially for its psychological effect on the Japanese. The prewar, nonindustrialized Japanese were largely a nation of fishermen, and the fishermen dreaded sharks for the devastating damage they could do to their nets and catches. Thus the shark became a fearful symbol of evil to the Japanese.

The tiger, a national symbol of strength and vitality for the Republic of China, was reportedly used by Chinese newspapers in describing the heroic exploits of the AVG. They were hailed as the "Fei Weing" - Flying Tigers. Henry Porter, a Walt Disney artist, created the insignia - a winged Bengal tiger flying through the Allied V for victory.

The name will not soon be forgotten, and it is unlikely that there will ever again be a tale of courage and accomplishment against overwhelming odds quite like that of the Flying Tigers.

| (Internet/Editor's note: Former Tiger Robert T. Smith, from whom much of the information for this article was obtained, has written a book, titled Tale of a Tiger. It is the first book about the Flying Tigers written by an actual member of the group.) |

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE SEND COMMENTS

TALE OF A TIGER REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN THEATER OF WORLD WAR II

Visitors

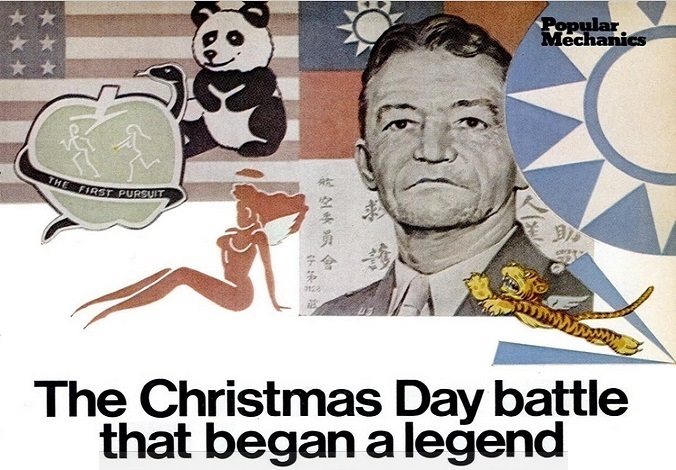

Rare color photo of Flying Tiger P-40s in formation shows famous shark mouth symbol - fearful sign of evil to Japanese.

At top are portrait of group's commander, Gen. Claire Chennault, and squadron emblems.

Rare color photo of Flying Tiger P-40s in formation shows famous shark mouth symbol - fearful sign of evil to Japanese.

At top are portrait of group's commander, Gen. Claire Chennault, and squadron emblems.

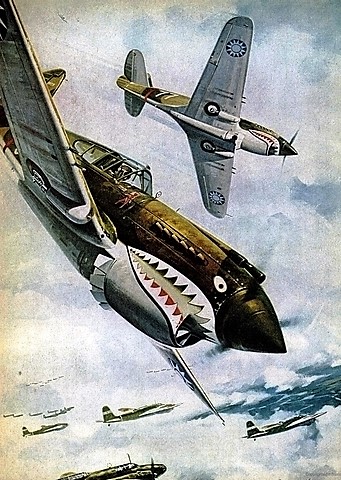

Flying Tigers in action painted by author/artist Roy Grinnell, depicts the incredible Christmas Day air battle - biggest single combat engagement

fought by the Tigers - in which 12 volunteer American airmen took on about 100 Japanese bombers and fighters and downed 28 enemy aircraft - without a

single loss of life of their own.

Flying Tigers in action painted by author/artist Roy Grinnell, depicts the incredible Christmas Day air battle - biggest single combat engagement

fought by the Tigers - in which 12 volunteer American airmen took on about 100 Japanese bombers and fighters and downed 28 enemy aircraft - without a

single loss of life of their own.