As you may have noticed, the "jungle story" covered some of the human aspects of "the Hump" operation, but because of wartime security and censoring, no specific operational and geographical information is contained in it.

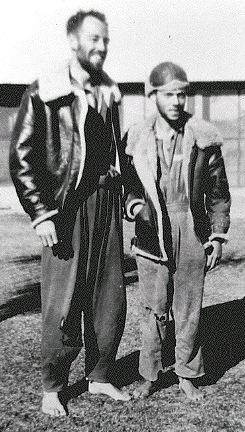

Lt. Cecil Williams, left, and Cpl. Matt Campanella, after having arrived at a field hospital,

wearing the clothes they wore throughout their ordeal.

Lt. Cecil Williams, left, and Cpl. Matt Campanella, after having arrived at a field hospital,

wearing the clothes they wore throughout their ordeal.

|

To begin with, I was a flight radio operator with the 13th Ferrying Squadron based at Sookerating Air Base (a U.S. airfield carved out of the tea plantations of the Dum Duma tea company) in north east Assam, India, just about where the Himalaya Mountains begin and where China, India and Burma come together geographically. I had left the continental U.S. from Morrison Field, West Palm Beach, Florida in July 1942 as part of a 5 man aircrew (pilot, copilot, navigator, radio operator, crew chief) taking a C-47 transport airplane to India. Our route took us across the Caribbean to South America, to Natale, Brazil. From Natal we flew the south Atlantic via Ascension Island to Accra, Gold Coast in Central Africa, across Central Africa to the Middle East and eventually Karachi, India (now Pakistan), arriving Karachi some time in August 1942. Since the bases in Assam were not yet quite ready, I was held up there in Karachi in a British base outside of Karachi called "New Malir." I finally arrived at Sookerating sometime in October 1942.

The 13th Ferrying Squadron was part of the 1st Ferrying Group which consisted of the 13th, 6th and 3rd Ferrying Squadrons, located at Sookerating, MohanBeri and Chabua, respectively (and all near each other in Assam). The Hump aircrews consisted of a pilot, copilot and radio operator. Our mission was to fly-in supplies into China such as gasoline, ammunition, airplane engines, parts, jeeps and whatever else in support of the 14th Air Force ("Flying Tigers") and Chinese Army, who were isolated from the rest of the world. While we flew in supplies into China, our return trips were also used at times to bring out Chinese soldiers for training in India for future combat against Japan. On the day that I bailed out, we were on a return trip from Yunnan-yi, China with a full load of Chinese soldiers. Because of the altitudes required to fly over the Hump and the C-47's limited lifting capabilities, parachutes for the soldiers were not usually included.

During the flight, the airplane ran into a very severe storm in which it was completely engulfed with fog plus heavy icing conditions. Such a situation for a pilot can be truly terribly confusing and frightening. Especially when all you can see out of your cockpit window is nothing, and your plane is bouncing around and rapidly losing altitude over an uncertain mountainous terrain. For whatever reason may have flashed through his mind, the pilot gave the order for the copilot and myself to bail out while he would remain with the airplane and its cargo of Chinese soldiers who had no parachutes. And as you may well know, in the Army when an order is given, it is given and you obey. Especially in wartime!

As mentioned in the jungle story, we got the name of the native village from an old document that Salong Lot (one of the more intelligent natives) happen to have and showed us. I later found out that there is a Tarang River that flows in the Himalayas in the area that we were lost in and my guess is that Tarang is the name of the river that we were following and on which the village was located.

On the day following our being rescued and our arrival at the field hospital, the nurses attending to us insisted on taking pictures of Lt. Williams and myself with the clothes we were wearing in the jungle just for the record.

Lt. Williams and Cpl. Campanella with the nurses that cared for them at the field hospital.

Lt. Williams and Cpl. Campanella with the nurses that cared for them at the field hospital.

|

When I returned to the squadron from the hospital, my squadron mates were exceedingly happy to see me back, especially since Williams and I were the first U.S. airmen to have walked out of the Hump alive. They told me how the squadron had carried out many search missions for us, looking for evidence of our parachutes on tree tops somewhere in the jungles. When they found none, they eventually gave up, speculating that maybe our 'chutes had not opened and we had perished. It had been a practice in the squadron to maintain a memoriam list on the squadron bulletin board of all the men that had been lost to the Hump. It was entitled "IN MEMORIAM: To All The Men Gone West", where "West" meant home. Lt. Williams' and my name had already been added to the list. It was very sobering reading it.

I was rotated back from CBI to the continental U.S. in February 1944 and came back in a very similar manner as to when I went over. I came back as a Tech/Sgt. radio operator on a C-46 airplane being returned to the U.S. for overhauling. We followed pretty much the same route back in reverse as when I had gone over to CBI, across the Middle East, Central Africa, the South Atlantic, South America and the Caribbean to Hempstead Field in Florida. Also, before leaving CBI, I (along with many others) was honored by being awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal and the Presidential Distinguished Unit Citation for my service in CBI. - Matt Campanella

DECEMBER 31, 1942

Copyright © 2006 Carl Warren Weidenburner

COMPLETE RE-CREATED ISSUE OF ROUNDUP

TOP OF PAGE PRINT THIS PAGE

CLOSE THIS WINDOW