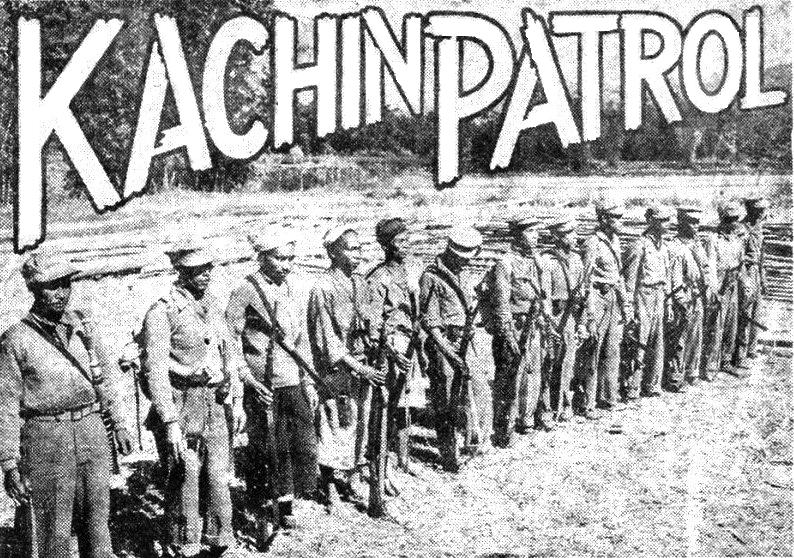

Lined up before a patrol against the Japs, somewhere in enemy Burma, is this squad of American Kachin Rangers,

with grenades, and native dhahs or bush knives, slung on their belts. Three new recruits have not yet

received their G.I. Clothing.

Lined up before a patrol against the Japs, somewhere in enemy Burma, is this squad of American Kachin Rangers,

with grenades, and native dhahs or bush knives, slung on their belts. Three new recruits have not yet

received their G.I. Clothing.

KACHIN RANGERS ROVE BEHIND ENEMY LINES

By S/SGT. EDGAR LAYTHA Roundup Staff Correspondent

(Editor's note: S/Sgt. Edgar Laytha, Roundup Staff correspondent, herein describes the Kachin Rangers, who have been operating under American Officers and Enlisted Men behind the Jap lines in Burma. Laytha was the first correspondent to live in a Kachin stronghold and campaign with the Kachin Rangers.)

BEHIND JAP LINES IN BURMA - An American liaison plane winged breezily over enemy land. The Killer was returning to Camp 4007, his secret base behind the Japanese lines. He was a long, tall, Texan, with tight lips and steel-blue eyes. A Captain in the U.S. Army, but of an organization I cannot reveal.

The Killer's real name, as his outfit demands, will remain a military secret until the end of the war. Every member of his Organization (this is how they refer to their own outfit) operates under a nickname. The Texan was named Killer in memory of the famous battle order: "Kill or sight! Ask No quarter. Give no quarter!"

JAPANESE BURMA

I was with him in the little plane. The main bodies of the Allies and Japs were fighting far behind us. The country beneath was Japanese Burma. The Japs patrolled it to keep lines of escape open for their main units should they be forced to retreat from North and Central Burma.

But the Japs were not sole masters behind their own front. The American Kachin Rangers also had their strongholds down below. Wherever the Jap moves or camps they are about. Nesting in the enemy's backyard, they ambush him on his own lanes, blow up his ammo dumps, dynamite his bridges, put road blocks across his trail, and build secret air strips on the grazing ground. They do all this under the leadership of a few bold American Rangers who belong to the Organization of which The Killer is a captain.

SECRET STRIP

We landed on a secret air strip near Camp 4007. Strange and colorful men were moving towards us from the jungle, many Kachins and a handful of Americans. The little brown fellows looked like children among the tall white men who came to the east a couple of years ago and welded them into a hard-hitting guerilla force which has fought ever since in all the battles of the Allied campaigns in Burma.

The work of the Kachin Rangers preceded every large engagement. After disrupting the enemy's rear, they joined in the final battles fought in the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys, making the Railroad Corridor insecure for the enemy. They were at Myitkyina, Bhamo, Kath, Namhkam and Lashio. Most of them had never been in an airplane before, but they bailed out into the enemy's backyard barefooted and with a Tommy gun in their hands.

RANGER STRONGHOLD

We crossed the clearing to a strip of jungle with open paddy fields on both sides. There, inside, lay Camp 4007, a Ranger stronghold. A tall and very lean American with a black goatee grabbed my hand so hard I felt my knuckles crack. He was a buck sergeant from Rhode Island, known as Blackboard in his Organization. He wore fatigues and carried a carbine, a never relaxed precaution outside the inner perimeter. The Japs once placed a 1,000-rupee reward on Blackboard's head. Similar distinctions haloed the heads of the other bold and picturesque Americans, with their cocky, broad-brimmed Ranger hats, the feathers of the jungle hen and the wild peacock waving from the band.

Equipped with the latest U.S. weapons, American Kachin Rangers like to use the bazooka against Jap trucks

and cars when on road-block operations behind enemy lines.

Equipped with the latest U.S. weapons, American Kachin Rangers like to use the bazooka against Jap trucks

and cars when on road-block operations behind enemy lines.

|

These Yanks were fighting men of all Services, soldiers, sailors, and Marines of all grade and rank, who joined the Organization as volunteers in Washington. Yet, you couldn't see who was soldier or sailor, major or lieutenant colonel. All of these men, regardless of rank or age, call themselves in the field by their first or nicknames.

HILL PEOPLE

Camp 4007 was a stronghold indeed. The jungle clearing was held by ingeniously concealed machine gun, mortar, bazooka and Bren gun emplacements. I could hardly detect them until I almost tumbled into a dugout manned by two sturdy youngsters of the Jing Hpaw people. Jing Hpaw, by the way, means hill people. The Kachins like to be called so because of hatred of the name, Kachin, which means sour-bitter and was given them by their traditional enemies from the valleys, the Burmans.

These Jing Hpaw boys sit with a juvenile enthusiasm in these dugouts. The average age of a Kachin fighter ranges from 14 to 21. Yet they remain boys and fighters until they become old men. Until then they get a supreme kick out of soldiering. It is in their eyes, their smile, their stride.

OUT-JAP THE JAP

Devilish experts of the jungle, the Kachins are comparable in their battle tactics to the American Indians. On one occasion, when an American unit trapped behind the Jap lines radioed for help, the Kachins infiltrated through the enemy lines, looked over the American positions, and returned through the Japs without having been noticed by either side. They out-Jap the Jap wherever they meet him. In the hill tracks, say military experts, a Kachin is worth 10 Japs. The Jap knows this. He tried in vain at the beginning of the Burma war to enlist the Kachins on his side. Later he forced them to hard labor and burned their villages.

Blackbeard of Rhode Island, who skirmished with them in countless escapades, spoke about their fighting technique while we were waiting for the approaching lunch hour. His Rangers usually creep up on an enemy position in a body and hit it with a tremendous amount of fire power. They unload the whole magazine for they see no sense in conserving firepower. If a Jap is hit with only one bullet, he gets the rest. After the kill they never retreat in a body. Everybody for himself is the Kachin slogan. Nobody covers anybody. The fighters meet after the skirmish at a pre-arranged rendezvous.

EXPERT SOLDIERS

Lastly, the Americans. They looked more like the 20th Century than the other Duwas. The Killer himself looked like a young, smooth-faced but shrewd American business executive. Skipper, a first lieutenant in charge of the center camp, reminded one of a college lad. An expert paratrooper, he once jumped into enemy territory during the monsoon, recruited 80 Kachins in the jungle and secured a vital airstrip in the enemy's backyard. Then there was Boston, a former officer in the Marauders and owner of a Silver Star. A debonair ex-newspaper editor, he looked, even in fatigues, like something from the social register.

Another company commander and ex-Marauder who hiked in for the conference was Scotty, a former Ohio fire chief. He was a kindly, soft-spoken man, yet he has 3,000 Jap rupees on his head. And there were the medics, radio operators, and pigeoneers - soldiers and sailors, young Americans just out of high school. They, too, were entitled to the name of Duwa, but now they listened religiously to plans and counter-plans evolved by other Duwas.

GOES ON PATROL

The company commanders left early in the afternoon, and for the rest of the day I thought about these Americans and the war they are fighting. None of them would exchange Burma for Europe. They would be little cogs in a monster machine, here they are kings, but their lives are just as much in danger. There is little romance in modern\

A Kachin youngster, his leg torn by Jap shrapnel, is treated by medics of the American Kachin Rangers behind

enemy lines in Burma.

A Kachin youngster, his leg torn by Jap shrapnel, is treated by medics of the American Kachin Rangers behind

enemy lines in Burma.

|

The Killer decided to send out a patrol early in the morning. he turned to me, "Here is your chance, Laytha. You'll go out with the patrol if you wish, but I can't guarantee you'll see Japs."

I laced on my jungle boots and left for Scotty's camp.

Before going to Scotty's camp to join the patrol, I had eaten a big meal with the men of the organization. Some of the Killer's company commanders (usually American lieutenants or sergeants) were coming in for a staff meeting to plan a new operation, and the Kachins killed a cow to serve their luncheon guests.

I sat between an Anglo-Burman and a British Major at the long, maheshift table reserved for members of the Organization. The young Burman daydreamed of a Shan princess he had once watched bathing in a mountain stream. The husky major was a fascinating character, of broad mind and great poise. He was one of those extraordinary Englishmen who are able to melt into a foreign tribe, learn their language and become himself a tribal leader. Lawrence of Arabia and the late Maj. Gen. Orde Wingate were such men.

Before coming to Burma as a timber cruiser, the major had lived in London's fashionable Mayfair district. Ice skating was his favorite sport, symphony concerts his favorite relaxation. In Burman he had married the pretty daughter of a Kachin headman, moved from the plains into a forbidden mountain country where only two white men had been before. There he has his home now - his Shangri-La.

A big fellow, he speaks six native languages fluently. Over the meal he told me of streams in his mountain country where there are gold nuggets big as the eggs of a jungle dove. Then he surfaced a little leather bag and poured the nuggets of which he spoke on the table.

ANOTHER NON-YANK

Another non-Yank in the Organization was a heavy-set chief of the Karen tribe and a former lieutenant in the Burma Rifles. He was a fellow you wouldn't want to meet in a dark alley. The American suntans he wore and the snappy little fatigue cap over his big brown brow couldn't soften the hard glow in his fearsome black eyes. Panther was his name, and so he was, although he filled more exacting duties, as the exceedingly efficient quartermaster of the Killer's battalion.

When I hiked into Scotty's hideout about seven o'clock one morning, the patrol, 40 Kachins and two Americans, was already lined up for roll call. The camp lay in the depth of a forest some five miles from the main camp. Scotty, the white Duwa, stood by with his G.I. radioman while a Kachin captain, the subedar, called the roll. It was answered by his lieutenant, the jemador, six non-coms and 30 privates. Their uniforms were mixed. The average ones wore British shorts, G.I. Shirts and the big felt hat of the American Kachin Rangers. Only the noncoms had field jackets. Their ratings corresponded to the importance of the weapon each man carried: the sergeants with the bazookas and Bren guns, the corporals with Tommy guns and UD guns and the privates with M-1's and carbines.

The jemadar checked the weapons and the supplies on the four pack elephants, then briefed the turbaned elephant riders and the local Shan guides who are recruited right on the spot wherever the force operates. Then he blew his whistle; the whistle Duwa was going to speak.

THREE DAY MISSION

"We were going out on a three-day mission against the Japs. We are going down to a trail junction to set up an ambush where the Japs have to return for water if they are going to remain in the neighborhood. Rifle section will lead with two scouts and a guide at the front. Weapons section will follow in this order: machine gun, mortar, bazooka. Six rifleman will remain in the rear with the elephants all the time to keep them and their riders from running away during the action.

"Our mission is not to take or hold ground, but to find the Japs, ambush them and do as much damage as possible."

The Duwa called for his camp medic, a baby-faced young American corporal whose face had not yet felt a razor. He told him to take over the camp during his absence, replace the machine guns which had been pulled out with Bren guns, take the remaining elephants to the air-dropping field and haul back the dropped supplies. The

A U.S. Army officer (back to camera) talks over a coming operation with two Kachin officers, members of the American

Kachin Rangers who have disrupted Jap communications in Burma by their lightning attacks.

A U.S. Army officer (back to camera) talks over a coming operation with two Kachin officers, members of the American

Kachin Rangers who have disrupted Jap communications in Burma by their lightning attacks.

|

SLOW PROCESSION

It was rather a slow procession. The patrol filed through long, narrow gorges, open forests and wide clearings. The elephants were a handicap. These big beasts can easily push a couple of freight cars onto a siding, but will carry only one tenth of their own weight, which means about four to five hundred pounds. They are the poorest pack animals on the trail. Yet behind the lines they are more practical than the sturdy mules, which would have to be flown in, whereas elephants can be hired on the spot just as you would rent a bicycle in Calcutta.

The footprints of the Japanese who had tried to infiltrate into Scotty's camp the night before were clearly visible and easily recognized by the slenderness of the prints and the hob nail marks left by their shoes. According to the Jemadar we were on the trail of about 15 men. After the first three miles, however, the Jap footprints turned into the forest. The grass they had stepped on had not yet risen. But we were not going to digress; Scotty stuck to his orders for the Killer: ambush the Japs at the watering place.

From then on the only footprints were those of tiger paws, the tracks of wild elephants, bad the hooves of Sing, the large wild cow of Burma. Our party passed in absolute silence through the forests while eyes gazed into the woods flankimg the trail. It took us a whole day to do 15 miles on easy terrain. Then the Kachin KP's cooked curried rice for the vening meal and soon everyone lay in his self-dug hole near the watering place, where six of our eighth Kachin soldiers set up an ambush.

SLEEP DIFFICULT

Sleep was difficult. The woods cracked and rustled, and we never knew whether the noises were caused by the Japs or by our own elephants, who had to be turned loose to forage for their food.

I made a nocturnal tour around the foxholes with a young Kachin interpreter whom Scotty wants to educate in an American college after the war. I was curious to see what the "little Rangers" would talk of before they fell asleep. Well, they are girl crazy at times, and their love affairs are very much alike. Lamour among the Kachins is generally this way:

The girl always plays hard to get and the boys have to turn to the parents. But Papa Kachin is hard to get, too. The old man traditionally declines the lad's first proposals. Only after the third of fourth visit, after Papa Kachin has received 100 silver rupees, does he approve the courtship and the use of the love chamber, the inner sanctum of every Kachin home. At last the encouraged young man dares to sneak by night under the basha of his beloved, right beneath the girl's sleeping mat. He pierces a sharp bamboo stick through the floor and the girl answers with a love song. The song is the key to the love chamber.

THE CONSUMMATION

What happens thereafter is considered among the Kachins as the consummation of the engagement, which may last two or three years and end with a three-day wedding. But not always; the young man my change his mind during the long engagement. Then he will have the liberty of paying 300 silver rupees to Papa Kachin for a pre-marital divorce. Such a transaction always saves blood feuds between two tribes, since the girl's honor is preserved and the way cleared for another similar engagement.

But Lamour is not the main topic in a Kachin dugout. Far more fascinating are their battle stories. There are tales of the first bail-outs, of "bridge-busting" in the Railway Corridor bad of the deeds of their great tactical genius, Thunderbolt, the bold chief of the Jinn Haw people. Chief

NO JAPS

Our three-day patrol unfortunately had no such thrilling experiences. The Japs did not come to the watering place. We went after them to a village supposed to have been one of their headquarters, but the Japs were gone and with them, the villagers. Yet a frustrated expedition like ours was typical of Ranger warfare behind the main fighting bodies. Guerilla's fighting in Burma is a nerve-wracking, hide-and-seek game. You may march for a hundred miles without seeing a Jap. Then, unexpectedly, when you are already tired and worn out he pops up and you need all your strength.

When I flew back out, the men of Camp 4007 were embarrassed. They had wanted me to see Jap-killing in the Japs' own backyard, but the hipless, bucktoothed robbers were on the run again. However, as you read this, Roundup's correspondent is behind the lines again on a new Jap-hunt with the American Kachin Rangers.

|

KACHIN PATROL

Story from the March 29 and April 5, 1945 issues of I-BT Roundup

Copyright © 2007 Carl Warren Weidenburner

TOP OF PAGE PRINT THIS PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE

SEND COMMENTS CLOSE THIS WINDOW