CLICK ON MAP TO VIEW ENLARGED IN A NEW WINDOW

CLICK ON MAP TO VIEW ENLARGED IN A NEW WINDOW

Contour map above shows what the Fourteenth Army's 700-mile front of forests, mountains, swamps

and jungle looks like from the air. The areas where the main fighting took place are picked out by white lines.

Calcutta, main Allied base for the whole front, is 200 miles west of Comilla - quite off this map.

Note how each battle area, though separated by huge ranges, remains an integral part of a vast,

unified front. Enemy documents captured in the Arakan reveal that the Japanese High Command confidently expected

their offensive on the Southern Front to suck-in Allied reserves from the Central Front.

Similarly, one of the main aims of the enemy offensive on the Central Front was to cut the life-line

feeding General Stilwell's troops advancing towards Myitkyina along the Northern Front. This life-line is the

Bengal-Assam railway which runs in a wide arc from Calcutta and up the Brahmaputra Valley to Dimapur (Fourteenth Army

railhead) then along to Ledo where Stilwell began his Road.

The Allies also linked the Central and Northern Fronts in one plan - flying in Wingate's Invasion

forces from behind the Imphal mountains into the land between the main Jap bases for both fronts.

The advantages enjoyed by the enemy on these two fronts in having superior road, rail and river

communications between the forward areas and their main bases at Shwebo, Mandalay and their southern port at Rangoon,

are obvious. Compare them with the solitary overland over-worked route serving the Allied front from Dimapur.

This handicap was overcome by development of air transport on a scale which, at the time, was greater than had ever

previously been attempted on any of the world's battlefronts and served as a pattern for many of the major air

operations in Europe.

|

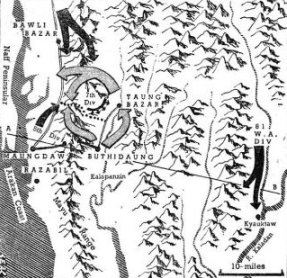

In their attempt to invade India from the south in February '44, the Japs made a forced march of 30 miles from

their bases around Bathidaung and succeeded in capturing Taung Bazar and the Ngakyedauk Pass. In one bold stroke

they drove a wedge between 5 Div and 7 Div, situated on separate sides of the Mayu Range, and also encircled 8,000

Administrative troops at Sinzweya. Drawing by Booker Cooke.

In their attempt to invade India from the south in February '44, the Japs made a forced march of 30 miles from

their bases around Bathidaung and succeeded in capturing Taung Bazar and the Ngakyedauk Pass. In one bold stroke

they drove a wedge between 5 Div and 7 Div, situated on separate sides of the Mayu Range, and also encircled 8,000

Administrative troops at Sinzweya. Drawing by Booker Cooke.

Not every time can supplies be gathered into the 'Box' as easily as here. An unfavorable wind will carry the

parachutes nearer to the enemy lines and a fight then follows for possession of the precious parcels.

Not every time can supplies be gathered into the 'Box' as easily as here. An unfavorable wind will carry the

parachutes nearer to the enemy lines and a fight then follows for possession of the precious parcels.

General Stilwell's forces battled their way from Ledo up to the watershed of the Hukawng and down through the

Mogaung Valley. General Wingate's skytroops landed astride the Japanese main line of communications to Mogaung

and Myitkyina from the south and southeast. Drawing by Booker Cooke.

General Stilwell's forces battled their way from Ledo up to the watershed of the Hukawng and down through the

Mogaung Valley. General Wingate's skytroops landed astride the Japanese main line of communications to Mogaung

and Myitkyina from the south and southeast. Drawing by Booker Cooke.

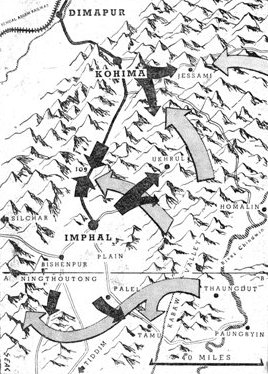

Five days after crossing the River Chindwin, in their second attempt to invade India, Japanese forces had scaled

the mountain barrier guarding India's eastern frontier and were in sight of the main British base of Imphal.

Simultaneously another enemy force was hitting hard at our positions around Kohima and the crack Japanese

33 Division was seriously harassing the withdrawal of 17 Division from Tiddim. Drawing by Booker Cooke.

Five days after crossing the River Chindwin, in their second attempt to invade India, Japanese forces had scaled

the mountain barrier guarding India's eastern frontier and were in sight of the main British base of Imphal.

Simultaneously another enemy force was hitting hard at our positions around Kohima and the crack Japanese

33 Division was seriously harassing the withdrawal of 17 Division from Tiddim. Drawing by Booker Cooke.