Tanks rolled up ahead of the convoy to clear the road of the last Japanese

and to end a two-year campaign to re-open the land route to China.

NORTHERN BURMA - When a few GIs in General Sherman tanks rumbled down the dusty road to open fire on the small

village that sunny winter morning, their shots were the last to be fired in the two-year campaign to re-open

the land route to China - one of the longest and toughest single campaigns in the Asiatic-Pacific war.

NORTHERN BURMA - When a few GIs in General Sherman tanks rumbled down the dusty road to open fire on the small

village that sunny winter morning, their shots were the last to be fired in the two-year campaign to re-open

the land route to China - one of the longest and toughest single campaigns in the Asiatic-Pacific war.

Strangely enough, the campaign was ending the same way it started when Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell launched the offensive early in 1943. It had opened with small beginnings when a few platoons of Chinese captured the tiny Burmese village of Sharaw. Gradually it had mounted to full-scale battles involving thousands of men, batteries of artillery and often platoons of tanks that besieged cities with buildings, cities like Myitkyina and Bhamo. But this morning it was ending with the capture of another obscure village, a place named Pinhai, by a few dozen men.

This time, although 80 per cent of the fighting for two years in Nothern Burma had been done by Chinese divisions, it was Americans who were spearheading the attack - GIs of the Chinese-American Composite Tank Group. I went along as a bow gunner in the command tank.

"There's the village straight ahead," said S/Sgt. Edward Zura of Chicago, the tank platoon leader, over the interphone at 0910 hours. "See that mound to the right of the biggest hut? Put your guns on it - it's a Jap machine gun emplacement."

At the 75mm gun in our tank, T/4 Robert M. Van Sant of Baltimore, Md., let a shell fly and it ripped open the mound with a flash and a cloud of smoke.

Suddenly we saw three shadows race behind a hedge. "get 'em - they're Japs!" yelled T/4 Theodore Janis of Pittsfield, Mass., the tank driver, from his seat behind me.

I trained the bow machine gun on the hedge and squeezed out short bursts, aiming the tracers low. Other tanks jockeyed into positions on both sides of us and raked the village with fire. Soon the four thatched huts in it were aflame, billowing smoke. The tanks ripped through the hedge an weaved in and out shooting at anything that looked like it concealed Japs and riding over two or three pillboxes to flatten them. At 0940 hours the tanks pulled out and Chinese infantrymen walked in.

We returned to an assembly area, unbuttoned our hatches, climbed out in the sun and ate K-rations.

Nobody had noted a single Japantitank gun, mine, mortar or artillery burst.

All we had encountered was a little machine-gun fire.

"not much of a battle, was it?" said one GI. "No - damn it!" answered another.

Just then a colonel raced up in a jeep.

We returned to an assembly area, unbuttoned our hatches, climbed out in the sun and ate K-rations.

Nobody had noted a single Japantitank gun, mine, mortar or artillery burst.

All we had encountered was a little machine-gun fire.

"not much of a battle, was it?" said one GI. "No - damn it!" answered another.

Just then a colonel raced up in a jeep.

"The road is open, men!" he declared obviously excited. "That village was the last spot there was any resistance. The Chinese 38th Division reports it has just pushed on two more miles to the Burma Road and hooked up with the Chinese Expeditionary Force that came from China. Your next mission is to go to the Burma Road, turn right and reconnoiter the ground near the road for two or three miles south, just so we'll know the area is cleared of Japs."

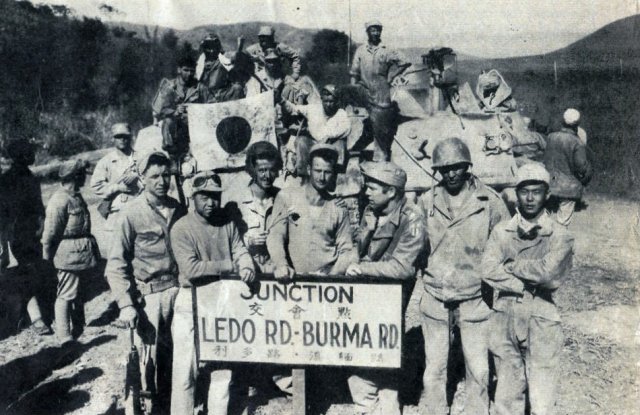

The tanks moved along the road that is the spur route from Bhamo to the Burma Road, bypassing a section where ther were Jap land mines, and reached the Burma Road junction at 1113 hours. When we reached it, Chinese soldiers in tattered blue-gray uniforms were there to meet us - the pings of the CEF who had fought their way from China over some of the highest mountains in the world. They gaped at the first sight they had ever had of a medium tank.

"Well, fellas," Zura said over the interphone, "this is somethin' to write home about. We're the first GIs ever to come over the Ledo Road to the Burma Road junction."

The tanks pushed south down the Burma Road as we buttoned up our hatches once more and closely scanned the countryside through our periscopes. Not seeing any sign of the Japs up on the barren, almost treeless hills on either side of the road or in the fields near the road, we headed back as little groups of Chinese infantrymen moved by, looking into each clump of bushes with ready guns. When we again reached the road junction, a big crowd of officers, GIs, Chinese soldiers and war correspondents was there, clustered around an open light tank. We asked what was up.

"Our light recco tank was behind you," explained Sgt. Steve Condon of Joplin, Mo., a machine gunner, "going down the Burma Road when all of a sudden a Nambu machine gun opens up on us - probably because we was the only open vehicle of the lot. Our tank commander, Red Miller (1st Lt. Eaton Miller of Hazar, Ky.) spots where the fire is coming from and we move over that way. Then we see two Japs firing the gun from a ditch, so everyone in the crew blasts away. After we'd poured enough lead into 'em, we got out and made sure they were dead. I guess you could say our tank killed the last two Japs in the campaign to re-open the Burma Road."

THAT WAS ALL the action there was to the last day in the drive that Gen. Joe Stilwell had begun two years before. The only outfit that had seen it all - from the first battle to the last - was the Chinese 38th Division which, like the Chinese 22nd Division that came into the campaign shortly after it, was run out of Burma by the whirlwind Jap ofensive in 1942. Both divisions were retrained and fully equipped by the Americans in India and sent back into Burma to become two of the best outfits in the Chinese Army. They and three other divisions - the 14th, 30th and 50th that were flown in for the Myitkyina battle last summer - did most of the heavy fighting, the power plays in the Northern Burma campaign.

But the Chinese alone could never have acomplished what they did. They needed the Tenth Air Force, whose Troop Carrier and Combat Cargo planes were the main supply line for the fighting troops with daily air drops of tons of food and ammunition and equipment, and whose fighters and bombers knocked out hundreds of bridges and other objectives in the path of the advance, besides reducing the Jap air force in Burma to the point where the sight of a single Jap plane was a rarity. They needed the American-led Kachin Rangers, whose behind-the-lines guerilla activity chased the Japs out of the mountains.

They needed Merrill's Marauders and their successors the Mars Task Force, which repeatedly sneaked around the flanks and cut in to throw road blocks to the rear of the Japs, causing their collapse up front for lack of supplies. And they needed the British and Indians of Wingate's Chindits, who were landed by Col. Phil Cochran's First Air Commando gliders 150 miles behind the Jap lines to spend months raiding Jap bases, wrecking railway tracks, blocking roads and blowing bridges. And the British 36th Division, which drove down the right flank of the main Chinese offensive toward Mandalay, forcing the Japs to split their defenses. They needed all these combat outfits, plus the thousands of GIs behind the lines in Engineer and Quartermaster and Signal Corps and hospital outfits who serviced them.

Similarly, although the Chinese Expeditionary Force, which launched its campaign by crossing the Salween River in May of 1944 to drive through to the road junction from China, did the ground fighting on that side of the campaign mostly thousands of feet high in the Kaoli Kung mountains known as "The Hump," they also needed support. They got it from the American Y-Force Operations Staff of Brig. Gen. Frank Dorn, which supplied them with radio communications, tactical assistance and supply lines. And they got it from the Fourteenth Air Force, which did the same job of supply and close air support in China that the Tenth did in Burma, only against the greater odds of a stronger Jap air force and a gasoline shortage there.

What made the campaign so tough was not just the Jap opposition, but the climate and the terrain. The June and September monsoons - worst in the world - bogged down trucks in hub-high muck, kept planes grounded or caused hundreds of them to crash in violent storms and shot up the disease rate. There were mountains rising to 5,000 and 7,000 feet, and jungles as thick as those on New Guinea, and thousands of rivers and streams. In the winter there was bitter cold, when infantrymen couldn't carry more than one blanket, and in the summer intense heat and rains - 140 inches of them in most places.

It was the walkingest campaign of the century, because it was fought in places where there were no roads. The Chinese 38th, for instance, walked more than 1,500 miles; the Marauders and the Chindits hoofed 700 miles and the Mars Task Force, 500 - so far. Unlike the infantry in most campaigns of the war, the pings and GIs and Britich here had to carry their own packs all the way instead of slinging them on trucks. There were mules to carry the pack howitzers and ammunition and radios and medical supplies. The casualties usually could only be evacuated to hospitals in one way: flown out one at a time in tiny L-5 liason planes piloted by sergeants.

As far as the GIs were concerned, it was a makeshift campaign in which bulldozer operators became tank drivers, clerks and radiomen became mule skinners, engineers became infantrymen, ordnance mechanics became tank gunners, mule skinners became artillerymen.

It was K-rations for weeks at a time. And it was a campaign where there was nothing in a town when it was captured - no wine to drink or girls to kiss, or sights to see, or celebration - but only a few thatched huts and a lot of stinking dead Japs.

The generals in evaluating the campaign, undoubtedly will stress its importance in re-opening the land route

to China and thus hastening the day of victory against Japan.

But there are a lot of GIs around here who are inclined to agree with one of the tankmen, who said:

"This here campaign is probably small potatoes compared to what's going on in Europe and the Pacific.

But I'll say one thing about it - it's sure as hell different."

Adapted from the March 17, 1945 issue of the China-Burma-India edition of YANK - The Army Weekly

Portions Copyright © 2004 Carl Warren Weidenburner

DAVE RICHARDSON YANK CBI EDITION

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE CLOSE THIS WINDOW