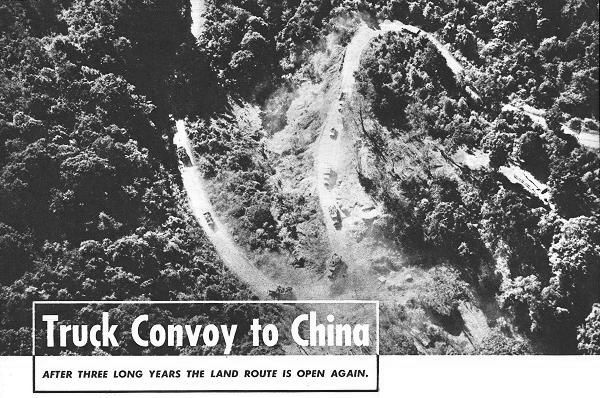

WITH THE FIRST CONVOY TO CHINA OVER THE LEDO-BURMA ROAD - The celebration of Pfc. Oscar Green's 21st birthday

was the biggest in his life. That, however, was only because of a coincidence. Green drove a jeep in the first motor

convoy in history from India to China. The day the convoy reached its destination at Kunming was also Green's birthday,

and although the Chinese people never heard of Pfc. Oscar Green, they did know one thing - the convoy had ended a

three-year blockade by the Japs of a land route to the Orient. So the people put on the wildest celebration in their

eight years of war. And not until then did I notice the change in Oscar Green.

When I started from Myitkyina, Burma, in Green's jeep, he had muttered: "To me this is just another dirty detail. Damned if I don't always seem to catch 'em." All through the trip he had stuck by that belief. "Who likes sleepin' on the ground?" he would ask. "Or cooking his own meals? Or getting windburned and chapped and covered with dust? I sure as hell don't."

Then, on Green's birthday, our jeep finally swung through the narrow streets of war-swollen Kunming at the end of the thousand-mile journey, and Oscar took in the scene. There were thousands of Chinese - some wrinkled with age and some tiny kids, a few of the wealthy in fine clothes and an overwhelming number of poor in tattered rags. They lined our path for miles, scanning the long procession of vehicles, waving banners, shooting off firecrackers, grinning, clapping and shouting. Green dropped his cockiness and cynicism. He grew silent. When he spoke again he was dead serious.

"You know," he admitted grudgingly, "you been hearing me bitch ever since we started, but now that it's all over I guess I was wrong in a way. I'm sorta glad now we made the trip because somehow I feel this thing's gonna go down in history."

Most of the rest of us in the convoy went through the same transformation as Oscar Green. Those of us who realized early the significance of what we were doing were backward about saying so, afraid of being laughed at. Sooner or later everyone began to sense something in the patient faces of the Chinese people; in the lavish celebrations they insisted on throwing for us in their war-shattered villages; in the holidays they declared at each place we passed through; in the pathetically flattering signs that called us "gallant heroes"; in the thumbs-up greetings and grins we got from the long lines of ill-equipped, underfed Chinese soldiers trudging wearily back to the front.

This was more than just another long drive over dusty roads. This marked the closing of one chapter in this war in the Far East and the opening of another. Thousands of Chinese, American, Indian and British soldiers had fought, worked and died in Burma and China to make this trip possible.

The convoy rolled out of Ledo in Assam Province of India even before the Japs had been completely cleared from the Shweli River Valley - the last link in Burma between Ledo and the Burma Road. Three days and 260 miles later the vehicles pulled in to Myitkyina, the biggest American base in Burma, and waited. After a week the convoy got the go-ahead from Lt. Gen. Dan I. Sultan, CG of the India-Burma Theater, who announced that farther down the road the last pockets of resistance were being mopped up.

We got up in the darkness next morning, dressed with chattering teeth, drew 10-in-one rations, packed our bedding and equipment in the vehicles and gathered at the push-off point. At 0700 hours Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Pick of Auburn, Ala., who had directed most of the Ledo Road construction and was to lead the convoy, called the drivers together for a last-minute meeting. "Men," he said, "in a few minutes you will be starting out on a history-making adventure. You will take the first convoy into China as representatives of the United States of America. It's up to you to get every one of these vehicles through. Okay, start 'em rolling."

As I got into jeep No.32 with Green and Pfc. Ray Lawless of Brooklyn, a photographer for the Signal Corps, I noticed that a Chinese driver was climbing into the cab of every truck as assistant driver. Other Chinese soldiers, veterans of the Burma campaign, were boarding the six-by-sixes to serve as armed guards for the convoy.

By 0730 the parking lot was filled with the noise of engines as the vehicles rolled out, turned into the Ledo Road and headed south through the early morning mist. There were motorcycles with MPs, jeeps and quarter-tons, GMCs and Studebakers, ambulances and prime movers.

The convoy thundered along, stopping only for a K-ration lunch. We passed American engineers, bulldozers and graders, Indian soldiers digging a drainage ditch, and Chinese engineers building a plank bridge. Fifteen miles from Bhamo we came upon a macadam highway that had been built before the war, and by late afternoon we were pulling into a bivouac area. A GI tent camp had sprung up all over Bhamo in the month and a half since its capture, and it had been policed up considerably. Nevertheless, when Lawless got out of the jeep to take a picture of the convoy entering the shell-blasted city, he found it hadn't been cleaned up quite enough.

"Phew," he said, turning up his nose as he came back to the jeep, "what a stink back there. Someone forgot to bury what was left of a Jap hit by mortar."

More vehicles joined us at Bhamo, increasing the number in the convoy to 113.

At dawn the next day we were off again in the morning mist, bypassing a knocked-out bridge. Soon we plunged into the jungles and hills, following an ancient spur road that had first been used by foot travelers in the day's of Marco Polo and before the war was the main route for supplies from Rangoon.

|

That afternoon the convoy descended the hills to the fertile, open country of the Shweli River Valley and entered Namhkan, which had been captured by the Chinese 38th Division only nine days before. Before we got through the battle-scarred village, an officer halted the first jeeps.

"Looks like you'll have to lay over here a few days," he said. "The Japs still hold several miles of the road up ahead. Some of them are right up there in those mountains, five miles away, with artillery, and they can see every move we make. They forced our guns from one position yesterday with their 150s."

The convoy went a few miles past Namhkan, and pulled into a wooded area that had been the Jap stronghold a few days before. There were cleverly concealed emplacements everywhere. Unpacking, we could hear the dull thud of Jap shells miles away and occasionally the sound of Chinese mortars. The drivers were wide-eyed because this was the first time most of them had ever been so close to the enemy.

While everyone lolled about the next day, I went around and talked with some of the drivers. All were members of Quartermaster trucking companies. Like Green, who hails from Taylorville, Ill., most of them are from small places like Ada, Okla.; Imlay City, Mich.; Oakland City, Ind.; Oconto Falls, Wis., and Pikeville, Ky.

Most of the veteran GI drivers here are Negroes who have been piloting trucks over the Ledo Road for 18 to 24 months. In fact, 90 percent of the convoying on the Ledo Road for more than a year was done by Negro drivers. "Them monsoons was the toughest part of it," said Wilbur T. Miller of Tupelo, Miss. "Last summer, for example, there was several feet of water in some places, higher than our hub caps. The whole road was sometimes just a sea of muck. The rain seemed to cave in a couple of tons of earth on the road in different places every week, and all we could do was set there waiting for a couple of days till the engineers could shovel it off. And boy, that ain't fun."

On our fourth afternoon in Namhkan, Gen. Pick got a message that American-manned General Sherman tanks had spearheaded the final break-through along the road to the Burma Road junction, so next morning we were off again. Within two hours the convoy arrived in the village of My-Se - where the last big battle had taken place - for a celebration.

Into the leveled town came troops of the Chinese First Army and men of the Chinese Expeditionary Force, who had driven through from Burma and China over the last six months to clear the Japs away from the Ledo and Burma Roads. The two armies were a strange contrast. Soldiers of the First Army, who had fought in Burma, wore sun-tans, GI helmets and British packs, and carried Enfield rifles and tommy guns. They looked plump and well-fed. But the Pings of the CEF, who had fought through from China, wore everything from ragged and patched blue uniforms to clothes they had stripped from the bodies of Japs. Only one man in every squad seemed to have a weapon - usually an ancient German rifle or a Jap Arisika - and all of them looked half-starved. The difference between the extensive American air and land supply lines to Burma and the blockaded land route to China that made military supply in quantity impossible. Looking at the contrast, some of us caught on to the significance of the convoy.

From My-Se the convoy wound through barren hills to Mongyu and rolled into the macadam highway at right angles to the Road, past a signpost that had just been put up at the intersection: "Junction - Ledo Road - Burma Road." Just 20 hours before, tanks had cleared this junction and now for the first time in three years a convoy to China had arrived at the Burma Road. But we didn't stop. The trucks swung left, passing more ragged single-file columns of the CEF as we headed for the China border.

On top of a hill 10 miles from the Ledo-Burma Road junction, our vehicles halted and the drivers were ordered to put Chinese and American flags and red-white-and-blue streamers over their hoods. The convoy started slowly downhill and halted near an open field. Thousands of Chinese and American soldiers were massed before a platform containing more American and Chinese generals than had ever been on a stage together in the previous three years of the Asiatic War. After the speeches and the band music, Gen. Pick's jeeps drove through an arch decked with garlands of leaves and signs and ribbons. Behind the arch was a short wooden bridge over a muddy stream. This was the Burma-China border. The vehicles crossed the bridge and continued on through the border town of Wanting to bivouac near a tiny village named Chefang.

For the next two days the convoy thundered through places that had been the battlegrounds of China during the last six months. The road wound a thousand feet up into the Kaolikung Mountains, which are part of the Hump on the air route between India and China. After hours of threading our way along the narrow mountain ledges we came around a bend and could see below us the blue ribbon of the Salween River, which had been the Chinese line of western defense for two years until the CEF offensive began last May.

That afternoon the convoy came out of the hills into Paoshan. A Chinese Army band blared as we rolled toward the city gate, school children waved banners, firecrackers crackled and signs were plastered everywhere welcoming "Commander Pick and his gallant men" and "More M1 munitions and all kinds of materials." That night there was a big party in the Confucius Temple for the whole convoy. There were more speeches, an elaborate Chinese meal, acrobats and gombays. Except for the difficulty of trying to eat with chopsticks, gombays gave GIs the most trouble. Gombay is the Chinese toasting word meaning "bottoms up," and three or four gombays with small tumblers of rice wine, which tastes like wood alcohol and is called jing bao or air raid juice by GIs stationed in China, can be as powerful as a whole case of beer. Nevertheless the Chinese proposed toasts every 10 minutes, and the GIs, in their desire to be diplomatic, soon were feeling no pain at all.

Next day, despite hangovers, we made the longest day's trip of the whole journey - 150 miles through rice paddies and up into the mountains again. Finally, at 1930 hours, the convoy halted in an open field. As we fumbled around with flashlights to get our gasoline cook stoves going and put down our bedding rolls, a GI started beefing. "Why the hell is it," he asked, "that every time we bivouac - except for last night when we slept on a concrete warehouse floor - we always have to do it in an open field on the highest and windiest spot in miles?"

As it turned out, the next three nights were to be spent the same way. We had all brought jungle hammocks along, but in the open fields the only place to string them was between trucks or guns or jeeps. Most of us just laid our blankets on the ground. This particular night it was so cold that when we awoke next morning there was a frost on our blankets. Lawless had to use our gasoline stove to melt the frost off our windshield.

The convoy pushed through Yunnanyi and another celebration, then camped as usual on a high, windy spot about 20 miles away. several GIs were in the streets of Yunnanyi to greet us, and one held up an empty beer case and yelled: "Where's the beer? We only got two cans this month and four in December." From then on, as far as we went into China, we heard the same question whenever we met American soldiers.

Beyond Wanting there were stone blocks beside the road that announced the number of kilometers to Kunming. I watched them hour after hour, day after day, as they diminished from 960 to 812 to 668 to 449 to 303 and finally to less than 100. We learned a kilometer is five-eighths of a mile and we periodically figured out our mileage as we drove along.

|

That night was the worst one of the trip. A heavy rain started around midnight, soaking us and most of our personnel equipment. In the morning we put away our dirty fatigues, took our wool uniforms from our barracks bags and dressed for the last night and the biggest celebration of all. "This Kunming must be a chicken place," said Green. "We even gotta put on ties." Again we put the Chinese and American flags and streamers on each vehicle. Gen. Pick called the GIs together.

"I'm proud of you men," he said. "You've brought every one of 113 vehicles through safely. I'm going to see that each of you drivers gets a letter of commendation."

The Chinese drivers climbed behind the wheels for the first time and the convoy moved to its destination. We were tired, our clothes still wet from the night's rain, our lips chapped and our faces and necks red with windburn. We all knew what to expect - more crowds and signs and arches and banners an speeches and parties.

Beside me, Oscar Green was quieter than usual. For one thing, he'd been feeling pretty sick, so sick we had stopped our jeep the day before at a hospital along the road for him to get some pills. When he came out he said they wanted to keep him in bed there because his temperature was over 100. But he refused to let Lawless or me tell anyone about it for fear he wouldn't be allowed to finish the convoy. The other reason he was so quiet was that he'd been figuring out something in his mind.

"They asked for volunteers among the drivers to fly back to Ledo tomorrow, instead of hanging around Kunming for a few days to rest," he said, "and I told 'em I wanted to go. I wanta get behind the wheel of a big ol' GMC and really boot it. This convoy was too much of a circus with all this celebration. I betcha we can make it in 8 days next time instead of 12."

"Happy birthday, Oscar," I said, as the first truck convoy to reach China in three years rolled slowly toward the

0-kilometer marker.