Scroll down to view...

January 24, 1943 - British Edition. |

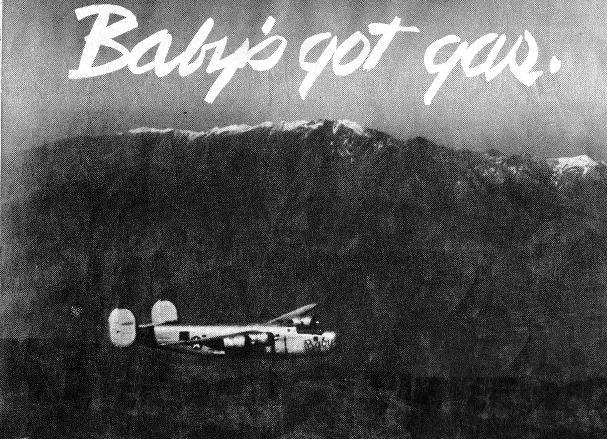

INDIA - "I've got to make up for some of the dough I lost when I came into the Army," said Sgt. Clarence Brady of Bridgeport, Conn., when we asked him what he thought of being a tankerman. "I'm after extra flying pay," added the aerial engineer, "and even if things do go wrong, there's always one consolation - we'll never know what hit us." Accompanying his words, Baby's engines were full and heavy in our ears. Looking out of the tiny flight deck window on the port side we could see the lowlands of India slipping away beneath us. The hills were blending into mountain ranges whose tops were getting higher and higher and more menacing. Only a short time before, at the briefing, the voice of the S-2 man had said: "If you can't get down at your destination, you might be able to locate another field. There are enough auxiliaries for you to get in somewhere. Above all else, watch your cargo. It's more precious than gold right now, and touchy as nitro." Our cargo was High Octane gasoline. "Play it smart and you'll get back okay," the tanker's Tech Rep had said yesterday when he inspected Baby for the first time. His name was Parker and he was one of several trained specialists sent over to watch the converted B-24Js - like Baby - and offer information and advice, and perhaps extend maintenance or re-work suggestions. Now we were on our way, heading for the distant mountains while up front Lt. George Heggy of Canton, Ohio, the pilot, and Lt. Paul Fisher of Shenandoah, Iowa, co-pilot, sat slightly hunched before the twin banks of instruments. Heggy, 28, had done a lot of flying in civilian life. "I'll wind up with my own plane again," he said. "You'd think that after I got through with this stuff I'd get the hell out - but I won't." An hour or so out, we had taken our first deep breaths. Always with the "hot juicers" you sweat out the take-offs and landings, and only after the first few hours does your blood seem to circulate again. In the beginning, the juice had been shipped in drums, almost vapor-sealed. But as the demands became greater, a new method had to be devised that would carry the needed loads. The drums were dispensed with and, converting a B-24J Consolidated-Vultee bomber into a C-109 tanker, the gas was now being transported in special bomb-bay tanks. Thus the men began dealing with an unseen foe - a vapor so sensitive that the slighest spark would

Here inside Baby we noticed the lack of armament. There was no waist gun and even the mounts and auxiliary features had been stripped away. Everything pointed to less gadgetry and more gas. The top turret was out, with only the small emergency bailout hatch to show for it. The nose was capped. And in the tail, where a gunner might have had a brace of .50s, now the torpedo-shaped auxiliary gas tank from a pursuit-type plane was installed. We were getting hungry now, but we had left our musette bag with K-rations somewhere in Baby's midsection. We would have to cross the actwalk between the bomb-bay tanks to get it, a path so narrow that a man over 180 pounds has a hard time getting through. On each side the empty bomb racks look like a giant griddle, and with the gasoline in the huge black tanks to furnish the fire, a man could fry to a neat brown if he were caught on the walk when Baby blew. That is, if the blast kept him there long enough. It wasn't a nice thought at the time and it took us a long time and most of our appetite to forget it. CPL. LUDLOW LOZIER of Glen Ellyn, Ill., the radio operator, wrote something on a piece of paper and handed it to Heggy. He stood behind the pilot, talking for a few minutes, and when he went back to his seat his face was grave. "It's going to get rough," Heggy said, removing his mask to make himself heard as we approached. "I'm going to pull her up and see if we can get above it." We went back to our seat next to the port window. We had been too engrossed before to notice the change in the weather. Only when Baby took an exceptionally hard bounce did we sneak a look out of the window. But now we took a good look and couldn't see a thing. Outside the window a bleak, dirty grey mist covered Baby as she lurched, trying to climb above the soup. Fisher turned his head our way, wigwagged that we were now at 22,000 feet and still going up. Lozier, who had been twisting dials and banging at his key, left his stool and began an animated conversation with Heggy and Fisher. "Radio interference mus be pretty bad," Brady said. "The radio compasses'll got out, too, and we'll get lost for a while. Lozier'll probably send out a 'May Day' - that's an SOS except we call it a 'May Day.' "All ships in the air remain silent while ground stations fix on our signals. After a while, if our signals are being heard, they'll be able to give us our exact position. It works out pretty well," he said, "unless our signals aren't being received or we can't receive an answer. One way or the other, we're lost." He turned calmly to the fuel tranfer panel. The wing tanks still read full and now it was Brady's delicate task to transfer that fuel into the main tanks before the landing on the China side. This was a dangerous moment since the drain ing of the gas from one tank to another released large quantities of vapor. The smallest spark now would blow Baby apart. The transfer operation took 15 minutes, during which time all of us forgot the fact that we were lost. When it was over, Brady signalled to Heggy and the pilot returned to his job of climbing Baby out of the soup. Lozier finally made contact with the ground. We were off course slightly, having taken a beating from adverse winds, but we were within an hour's flight of our China destination. "We may have to get an instriment letdown," Lozier said, "but I'd rather we went to an auxiliary field if this fog doesn't lift." In this kind of country, Lozier explained, setting down with instruments with the pilot bringing in the plane blind was risky business. The ship lets down 1,000 feet at a time, calling in before and after each drop so that the ground station can be sure no other ship is flying at the same altitude. Much of China's terrain is rugged, with severe drops in sea level or tremendous rises and, in particular, an 8,000-foot mountain range which almost surrounds the China base to which we were flying our load. It was to this threatening girdle of jagged peaks that Lozier was referring. "But maybe the soup will lift by the time we get there," he said, hopefully. We began swinging in great circles then over the China base. Long minutes ago they had told us to await our turn for the instrument let-down. There were 10 other ships somewhere in the fog below us, all waiting for the opportunity to get down to unload the high octance, to a hot meal and safety. The radio, which was none too good at best because of atmospheric interference, remained silent until each five-minute period would pass, after which Lozier would hopefully call in for instructions. But the weather seemed to be growing worse. Then he got a call. We were to proceed to another base to the south where we were to effect a landing. Weather was reported to be a little better there while here the fog had closed in completely. It was zer-zero, they told us, and suicide to attempt a let-down. WE WERE 10 minutes out when suddenly Baby began coughing. Her No. 3 engine, the right inboard, was backfiring. We looked out the window. Heggy had feathered the propellor on the balky engine. In the heavy mist that partially shrouded the window we could see the stilled blades which had breaked themselves to a halt, leading edges cutting into the fog. We watched the engine nacelles for signs of ice. Severe icing conditions now, with one engine dead, would be as disastrous to us as if another engine went out on the same side. Heggy and Fisher were trying to start the dead engine again. "Sometimes it works," the pilot said, "after a few minutes' rest. I've seen 'em start cooking as if nothing had happened." They tried it once. The prop spun around two or three times. They tried it twice more. Again the prop spun, but it was more the action of windmilling in the air than any sign of life in the engine.

We were long overdue. Once, as we came down curiously to probe a lane of safety through the fog beneath us, a rift in the gray damp opened before us and we broke through over an airfield. We had been drifting off course again, but were still maintaining a comfortable altitude. Heggy pulled Baby around in great searching circles over the field. On the strip below, a plane began to move, gained speed, and with a sudden swoop, banked off the field. We could feel the power that surged through baby as Heggy pulled her up. "That guy's climbing too fast," he yelled. "That could just as well have been a Jap field we passed over." Lozier's radio wasn't having any today. The radio-op shook his head glumly. "Too much static," he said. "Can't get the damned thing to receive clearly and I doubt the ground stations can get us. Boy, the way that guy was climbing I thought sure he was a Jap." A glance at our watch revealed that we were near to being out twice as long as it ordinarily should have taken us to complete the trip. We didn't have enough gas to go back, perhaps would have enough gas to fool around in the sky but a few more hours. It was getting colder now. The tankermen don't get heating devices. Heaters are scrapped in order that their weight can be taken up by gasoline. They wouldn't be much good anyway since the tankers must be kept ventilated against the gas vapors. Brady was sitting slumped against his chute pack, taking things easy. We decided to follow the engineer's example so took a deep breath and closed our eyes. We came out of our doze when Lozier jumped up, kicking our feet as he clambered over them to talk to Heggy. Brady shook us. "Hey," he said, "we're in. Lozier got through. We're right over Shangri-La." "Lozier got through just as we were passing over the south end of the field," Heggy explained. "We're standing by for let-down instructions. The weather's a little rough here, too." Brady was grinning. "They've got about a half-mile visibility down below, so we ought to break through pretty soon," he said. We had come down 1,000 feet at a time in great circles while the radio-op called in our altitude at every drop. New we were below 5,000 feet and coming in fast. Heggy made a final attempt to start the dead engine, but it was no use. We broke through over the north end of the field. An intermittent rain mingled with the mist that hung sluggishly over the ground. Now Baby was roaring into the traffic pattern, banking for the approach. She came in slow, feeling her way, and we felt the slight tremor that ran through her as the short, stubby legs came down out of the landing gear wells. We were also conscious of another sound - more menacing - the slopsh of high octane in the big black tanks in her belly. Below us a jeep bumped onto the field. Behind it followed an ambulance and a fire truck. Baby hit and a shudder ran through her. But her stocky legs held firm and sure and she lumbered back from the end of the runway and waddled into parking position. by Sgt. FRANK T. MONTELEONE June 2, 1945 CBI edition |

November 30, 1945 edition. |

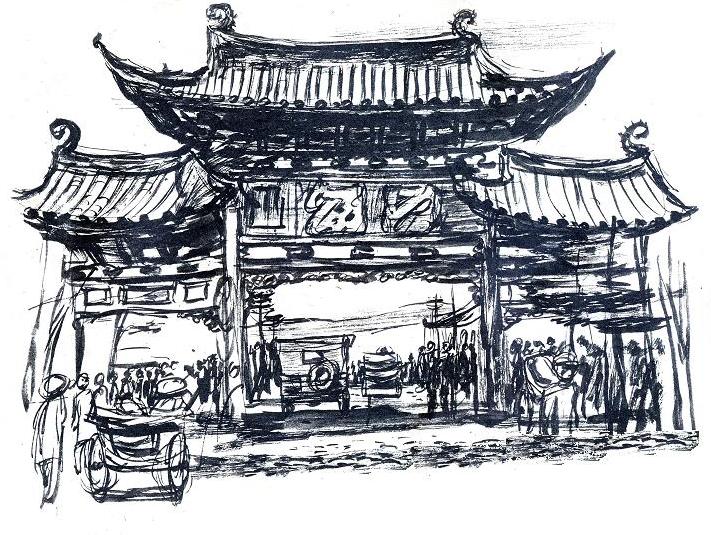

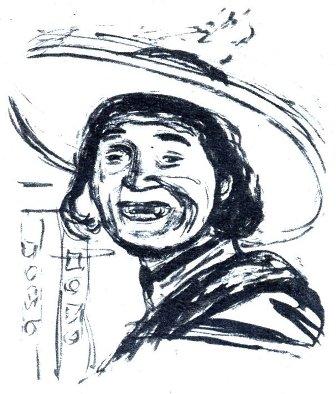

CHUNGKING, CHINA - Politically but not militaristically speaking, this war city is the Washington of China. You see very few American soldiers on the streets of Chungking, something that could hardly be said of other Allied war capitals. The GIs are here all right and well they know it. They appear scarce because sight of them is easily lost among the thousands of China's citizens who came here when they were chased out of their eastern homes by Japanese bombs and invasions. This is a city of an estimated million and a half set against a comparative handful of GIs. On the streets you see a make-shift life going on wherein each of the million and a half seems too busy to give much thought to what he has lost in this war. It goes on day after day with the same surprising amount of cheerfulness which makes you wonder where it comes from and then you remember that these people have been doing this for more than seven years. You would believe that a military uniform would be the last thing these people would be curious about. It's quite the contrary when it comes to American khaki. America's Joe is still the most interesting item in the city. That may, in a way, explain his absence from public places. It is not uncommon to see 25 to 50 Chinese gathered around a store window as though a wizard demonstrator was giving out with his best tactics. Standing before the window will be a GI looking at an old model alarm clock or trying to catch the trademark on a fountain pen. When he finishes his business of gazing he'll have to work his way through a crowd that builds up quickly and disperses just as fast when the soldier moves on.

It's just another of the hard-to-understand things about Chungking. A good explanation of this abundance of curiousity might lie in the fact that many of the city's present population is made up of pastoral folk undergoing their first experience in a huge city. For some it is the first time they see an American soldier and, for most of them, a jeep is surely something that must have come off another planet. That does not mean that Chungking is a metropolis of yokels. Chungking is also the home of China's highest society and the GIs are aware and appreciative of that, too. They have been the party guests of almost every governmental official in town. But despite this appreciation and the natural aptitude for the American to soak up this hospitality, there is still that great novelty about the socially-lesser part of Chungking. Two GIs caused a grand-scale traffic tie up once when they pulled off to the side of the street and lifted the hood of their jeep to make a minor repair. If an American soldier is on the move either on foot or in a car, no one pays much attention to him. Let him stop once to gape at some object and there's sure to be a crowd around him within a few minutes. Picture taking around the city is a near impossibility if you want to take pains at snapping a scene. You shoot fast or a gathering will hide the picture from your lens. If you find that you must change film in the middle of your scenic hunt, it's best to take cover somewhere. What miracles are performed on the inside of the camera are of much more interest to these onlookers than just the camera itself. So if you open it on the street you might have to brush out a few Chinese noses before getting it closed again. THE CHEERFULNESS and the friendliness never falter. Every kid old enough to speak will throw up his thumb and give you the hearty "ding hao" which equals the expression "America joe okay" all over China. As everywhere, the GIs have left a few expressions with the Chinese kids, especially the shoeshine boys. Someone must have spent hours teaching one particular expression because occasionally you'll get an offer from a shoeshiner along with a sales talk that goes, "C'mon joe, no goddam good shoeshine!" The English is as good as any Statesider could put it. A Chinese woman will not speak to strange men spontaneously but if ahe has a baby in her arms, she'll grab the baby's arm and wave it at a passing soldier.

The outfits stationed here make incessant remarks about their own relative comfort and their "battle of PerDiem Hill." Many of them come from the hotter spots in the war against the Japanese so the "plush" in this place is neither sought after nor accepted freely. An example of this is T/Sgt. Charles Stemm of New York City, who is now the sergeant-major at this headquarters. He's revengful over the Japs taking control of his things at Kweilin. Stemm was one of the last men to leave that city when the Japs were closing in. So now the mountain of paperwork he has to move daily isn't exactly what he's been trained for or used to doing. That goes for nearly all of the GIs here. They don't like the job of pushing out yards of paperwork that necessarily comes out of a headquarters like this. In spite of the dissatisfaction, there's not much of a morale problem in Chungking. The Provost Marshall's books have had only three entries in two years. Two of those are on a man who was picked up by the MPs twice, both times being booked for slugging an officer. Morale takes a beating by the mail shortage. Regular mail has to take a place beside a variety of high priority essentials flown over the Hump. Men here sometimes go for weeks without a sugar report. In comparing Chungking to Washington, there are some Stateside conditions that do not fit in the matching. A few oldtimers here assure you they can get an untoughed 1942 Buick crated and delivered, but the price in the present infaltionary whirl would be fantastic. An American housewife could have a field day browsing through Chungking shops. She could buy a flat iron and, with a little more search, could pick up an electric curling iron or two. You don't have to be the favored customer of a druggist to get a couple rolls of 120 (or any other size) film. If you have the price the film is yours. The current price for popular-sized film is 3,500 Chinese dollars a roll. The rate of exchange is not quotable but some idea of the mountainous prices can be had by referring to things GIs have bought. In a town south of here I paid 800 for a breakfast of coffee and doughnuts, neither of which were recognizable as such. The average restaurant price for a Chinese dinner for five people is about 5,000 Chinese dollars. There's only about one brand of liquor available and drinkable. That's a Chungking-distilled gin. At one time it was handled by the quartermaster as a regular grog ration. If the boys want to buy it independently they now pay about 800 dollars per fifth. It smells and tastes something like the Stateside stuff, but the newcomer

Here you can buy most any little item that has been sucked out of the American stores by the war. If you get nosey and insist on knowing where the merchandise comes from, some merchants will proudly tell you that his wares have been brought through Japanese lines from Shanghai and other occupied cities. The GIs do a good share of shopping in the "Commission stores" which are comparable to our own hock shops. However, in these commission houses you don't get cash on the line. If you're looking for ready cash for any of your posessions, you leave them with the storekeeper and maybe in a week he'll tell you, he can sell whatever you leave. If you want to make a purchase you pay the price that's marked on the tag. There's absolutely no use haggling. The price has been set by the owner and the storekeeper won't cut into his commission to make a sale. Many good bargains are sent home by GIs from these commission houses. They've been able to buy heirlooms that have been in Chinese families for centuries. Even more popular than commission houses is a middled-aged peddler who looks like he'd been pulled right out of a Hollywood setting of an Oriental scene. The GIs know him only as Mr. Fan who comes around every Wednesday to all the barracks to display his wares. He deals on a simple but effective credit plan. If you're short on cash, all you have to do is sign Mr. Fan's credit book and walk off with your purchase. He never bothers you further than that. His book is thick with names but so far, he says, he's never lost a penny on a creditor. GI HOUSING in this headquarters is unique in any Army set-up. Though only a few are stationed in this city, they live in four barracks spread in different parts of U.S.-leased real estate. They pay their lodging and food bill at the end of each month with funds paid the soldiers on a per diem basis. There aren't any nightly post exchange beer parties. The post exchange is open only one day a week, if and when supplies come in. And, for a better reason, because there simply isn't any beer around. The beer ration here could be termed about the most meager in the world. They get it once a year, at Christmas time, and then only four cans to a man. Other entertainment is very scarce. Movie fans are in a bad way if they're not satisfied with the three weekly pictures. There are a few shows in town but they offer a hard test for the nerves, eyesight and the nose. The sound is just a mad screech and the power system in the city is too poor to allow for elaborate movie houses. Outside the movies, there isn't much more. For the size of their group the men think they have the largest Red Cross club in the world. It's being operated now by Miss Ada C. Pagenkopf of St. Paul, Minn., and Mrs. Naomi J. Thompson of Washington, Pa. Madame Sun Yat-sen, widow of the Chinese Republic's founder, sees that the boys are occupied with all the social functions that she can round up. As another diversion, many are learning the Chinese language on a co-instructional plan. They teach the Chinese English and the Chinese, in turn, instruct the GIs on the pronunciation of everyday words and phrases. The blowout awaited for most is the annual New Year's dance which this year had the backing of six Chinese agencies. The dane was held at the Vitory House, a leading hotel, where they served a buffet supper and more of that bus-propelling gin. There weren't enough Chinese girls to go around but those who picked their partners early in the evening, danced to Bing Crosby records. The world's spread of military uniforms are seen by GIs here on the battery of war correspondents and embassy officials from all the Allied and friendly powers. The only regularly circulated Americanized paper in Chungking is the Shanghai Evening Post. It is run by a couple of Americans who must depend on printers who neither speak, write nor understand English. The GIs get the news mostly in bulletins furnished through Army facilities.

Men on the fronts who get to Chungking once in a while bring interesting and amusing tales with them. One is S/Sgt. John DuBois of Beverly, Mass., who is on loan to the Chinese Army as an instructor in the use of field artillery weapons. He and his five buddies were one of the outfits named recipients of a Christmas gift from Maj. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, CG of the China Theater. They were ordered to pack up and report to Chungking where they could spend the holidays. "There isn't much here, that's for sure," says DuBois, "but it's a hundred times better than what we have up there at the front so it didn't take long for us to get our stuff together." They had to travel on the Yangtze in a boat loaded with nosey pigs that roamed about the men's quarters all through the trip. Dubois wears the badge of a Maj. Guo Chung Kuang, "American Instructor." He gets extra special respect from Chinese officers and says, "At first I was a little embarrassed but now it doesn't bother me any more to have a Chinese general throw a highball at me." T-5 Bill Hamera of Detroit, now working in the Signal Photo Lab at this headquarters, has more to say about the reverse military courtesy he was shown at a Chinese outpost when he arrived in this theater. "It was a rainy night when I pulled in and the mud almost came to the fenders of our jeep," relates Hamera. "When we pulled up to the tent where I was supposed to quarter, four Chinese popped out and grabbed my baggage. They carried it on their shoulders and when I stepped inside the tent myself, I found they were four Chinese generals. There were five others in the same tent with them." Hamera is part of a three-man outfit on duty in the lab. They are here alone, have no officer and belong to no particular unit stationed here. The job they have, though, is about the most exasperating of the lot because of water and power conditions in Chungking. Many times when they're printing important work, the lights will suddenly cut out on them. The same thing often happens to the water supply so they have to work fast while the working is good. With Hamera are two California men, S/Sgt. Norris (Clink) Ewing of Ventura and Sgt. Charles (Dutch) Todd of Glendale. The three have never been separated since they came into the Army. In this city where it seems you're always walking up steps to get anywhere, the GIs have a special reverent name for the States. It's "Uncle Sugar" and any Stateside city is referred to as "Shangri La." This is the last air stop on the globe so the GIs have fittingly given themselves the name of "Dead End Kids." They put in a lot of time dreaming about getting back to Shangri La. by Cpl. JUD COOK - YANK Staff Correspondent - June 2, 1945 CBI edition |

June 2, 1945 CBI edition |

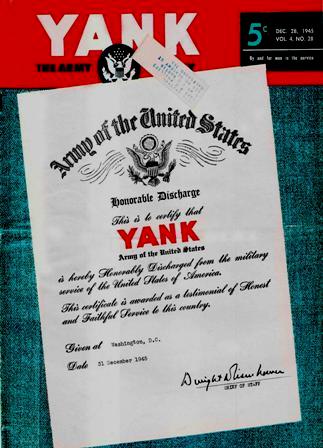

The cover of the final issue of YANK featured an Honorable Discharge from General Eisenhower. |

|

|

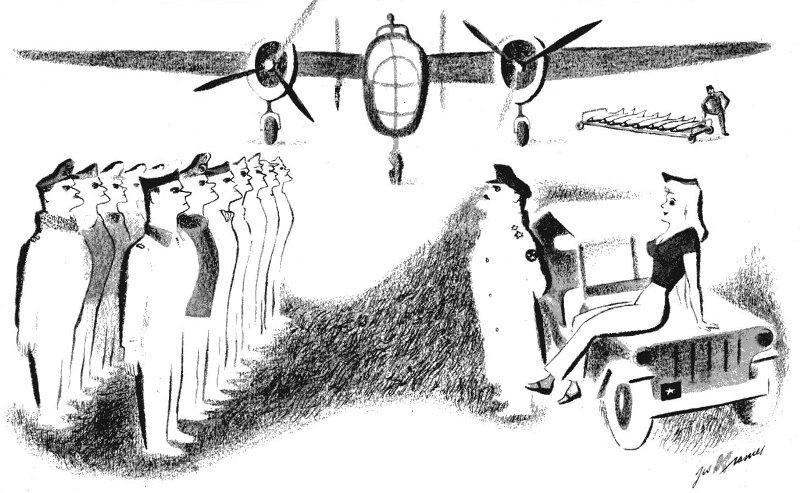

"I JUST WANT TO TELL YOU MEN THAT THE FUTURE FREEDOM AND HAPPINESS OF COUNTLESS MILLIONS MAY DEPEND ON THE SUCCESS

OF THIS MISSION - ALSO, MISS FROSTY CHALMERS HERE HAS PROMISED TO KISS THE FIRST CREW BACK."

"I JUST WANT TO TELL YOU MEN THAT THE FUTURE FREEDOM AND HAPPINESS OF COUNTLESS MILLIONS MAY DEPEND ON THE SUCCESS

OF THIS MISSION - ALSO, MISS FROSTY CHALMERS HERE HAS PROMISED TO KISS THE FIRST CREW BACK."

|

YANK

THE ARMY WEEKLY

China-Burma-India Edition

Part Five

Copyright © 2005 Carl Warren Weidenburner

CBI EDITION INDEX

Visitors

Since March 31, 2005

These eggs are of the 1000-pound variety

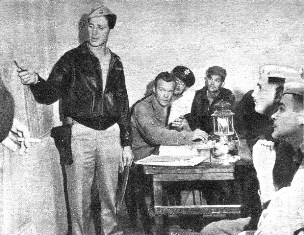

These eggs are of the 1000-pound variety Capt. Joseph Pirruccello points out the objective - RANGOON.

Capt. Joseph Pirruccello points out the objective - RANGOON.

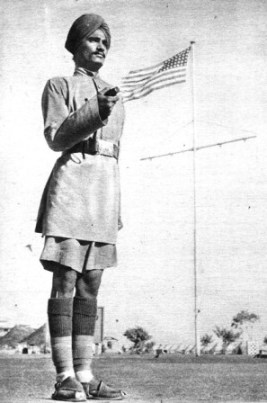

Sgt. Edward Sally, Houston, Texas,

Sgt. Edward Sally, Houston, Texas, The Himalayas, the mountains that make the India-China air route the "most dangerous in the world."

The Himalayas, the mountains that make the India-China air route the "most dangerous in the world."

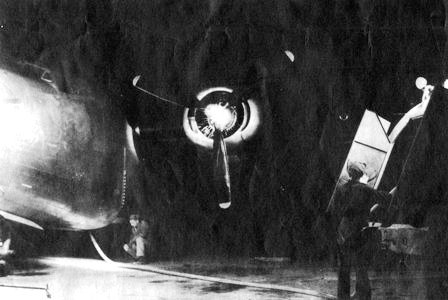

This is the baby - a B-24 - that carried the men and bombs all the way to Burma.

This is the baby - a B-24 - that carried the men and bombs all the way to Burma.

In the early hours, the Flying Tank Car gets her load of high octane bound for China.

In the early hours, the Flying Tank Car gets her load of high octane bound for China.

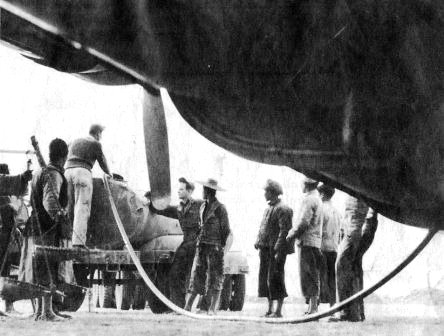

On the China side, ever-curious Chinese watch as Baby's precious but touchy cargo is unloaded.

On the China side, ever-curious Chinese watch as Baby's precious but touchy cargo is unloaded.

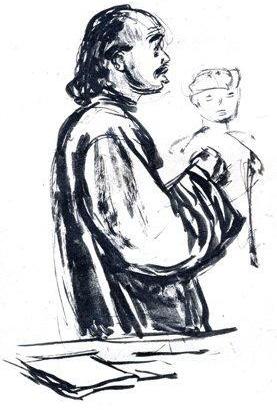

This Chinese fortune teller objected very strenuously to having his portrait

sketched.

This Chinese fortune teller objected very strenuously to having his portrait

sketched.

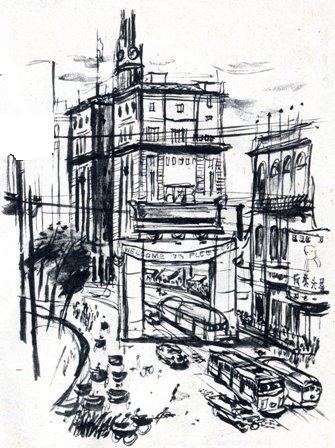

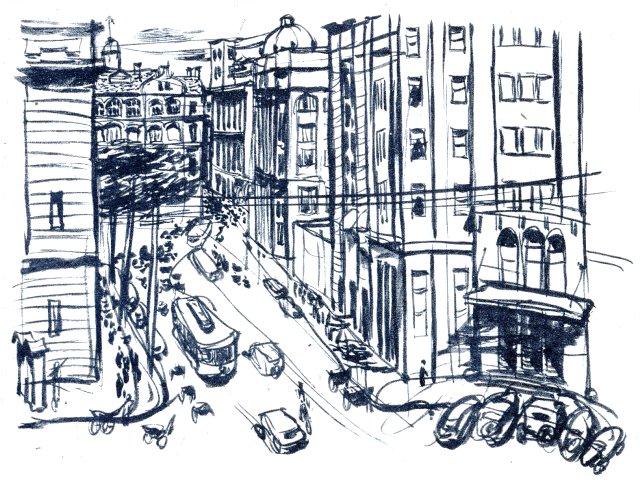

A side street in the International Settlement. It's unhealthy for a stranger to walk these streets alone at night.

A side street in the International Settlement. It's unhealthy for a stranger to walk these streets alone at night.

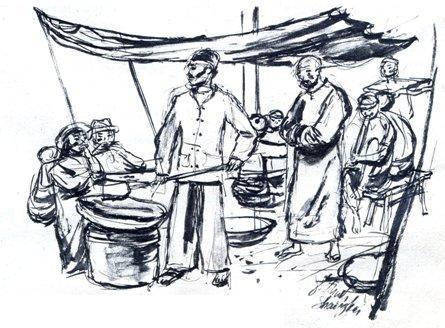

The city has many outdoor eating places like this one. The man with the

shovel is roasting walnuts over a

charcoal fire.

The city has many outdoor eating places like this one. The man with the

shovel is roasting walnuts over a

charcoal fire.

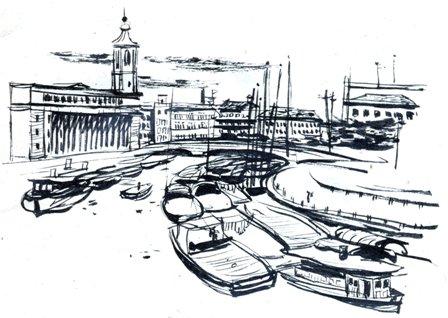

Families live for many generations on these houseboats on the Yangtze River.

Families live for many generations on these houseboats on the Yangtze River.

Parts of the International Settlement are as busy as any city scene back in the U.S.

Parts of the International Settlement are as busy as any city scene back in the U.S.

A Chinese soldier, doing MP duty in the city, takes some time off to hold a pose.

A Chinese soldier, doing MP duty in the city, takes some time off to hold a pose.

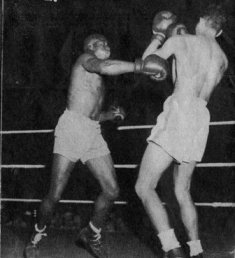

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

Pfc. James Williams, Beaumont, Tex., poises a left hook toward Leading Telephonist Dusty Miller of the RIN who

lost by a TKO.

Pfc. James Williams, Beaumont, Tex., poises a left hook toward Leading Telephonist Dusty Miller of the RIN who

lost by a TKO.

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

Pfc. James Williams, Beaumont, Tex., poises a left hook toward Leading Telephonist Dusty Miller of the RIN who

lost by a TKO.

Pfc. James Williams, Beaumont, Tex., poises a left hook toward Leading Telephonist Dusty Miller of the RIN who

lost by a TKO.

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

LAC Danny O'Sullivan of London mixes it with Aaron Joshua of Rangoon who took the decision.

Pfc. James Williams, Beaumont, Tex., poises a left hook toward Leading Telephonist Dusty Miller of the RIN who

lost by a TKO.

Pfc. James Williams, Beaumont, Tex., poises a left hook toward Leading Telephonist Dusty Miller of the RIN who

lost by a TKO.