|

|

After serving in World War I as an infantry officer, Elephant Bill settled in Burma where hebecame a teak man and boss of elephant teams. Early in 1942, when the Japanese swept acrossBurma and the regular ways out were closed, Bill put his wife and children on the back of anelephant and took them over the razor-backed mountain trails into India. Thousands of peoplewho tried to walk out along the same trails died on the way.

When his family was safe, Elephant Bill went back and rounded up all the elephants he could beforethe Japanese caught them, formed his company of elephants and became a unit of the Allied forceson the India-Burma frontier. Tall, rangy, sunbrowned and nearly 50, he is working his elephantsin country where Japanese raids are becoming more and more frequent and the bulk of the Alliedtroops are behind him.

Bill's elephants work in groups under the control of small Burmans who are born and trainedin the elephant business. These men are known as uzies (head-sit-men). From their fathersthey learn the strange double-talk of shouts, kicks and prods which the elephants seem tounderstand. One of these little brown men squats on the head of a great elephant, shouting andkicking the elephant's neck and prodding its ears with a long piece of iron as the elephantinches a log into place among others on a half-built bridge. If the ends of the log aren't quitestraight, the uzi shouts louder and kicks harder. The elephant kneels down and nudges thelog gently with his head, then stands back and has a look at his work. If it isn't right yet,more shouts and kicks come from the uzi. The elephant kneels down once again and givesanother nudge, headwise. The job is right this time so the uzi and the elephant go to getanother log.

|

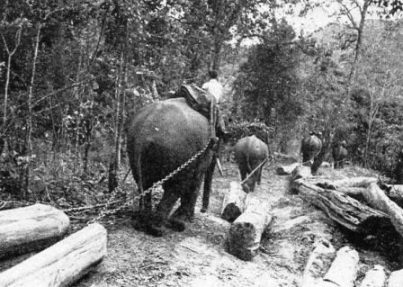

To drive piles, the elephant simply stomps down on a log with his feet. Culverts are built much the same way. Wearing chain harness, the elephants haul logs to the bridge or culvert site. Thenit is a question of pushing the log into the right place.

The bull elephants have tusks; cows usually haven't. The tusks save the bull elephant a lotof kneeling because they use them to roll logs. The cows have to kneel and push with theirheads. The elephants' trunks are enormously strong but they are very careful how they use thembecause, if their trunks are hurt, they are unable to feed themselves.

"I've seen bull elephants fighting with their feet and their tusks and keeping their trunks highin the air out of harm's way," says Elephant Bill. The elephant can pull or push six tons butit does not carry more than about 500lb. on its back. This seems small but it is a fair parcelof food or ammunition to small bodies of troops sitting on a rocky crag somewhere.

Pushing through heavy undergrowth, climbing over heavy boulders, moving carefully up mountainwater courses, the supply elephants from Elephant Bill's company go in to troops who mightotherwise be almost completely cut off from supplies.

Although these elephants take any amount of kicking and shouting from their uzies,they are tough about the hours they work. They work only four hours daily and this in the morning.They won't walk very far - 10 miles is usually their limit. They like to spend the rest of theday eating, sleeping and bathing. Elephant Bill's animals work from about 7 a.m. to 11 a.m.As the sun rises highest they knock off.

Elephants learn their working technique as calves born in captivity. When the cows go to workin the morning the calves go along too and watch and try to help.

"Sometimes it's a damned nuisance because the calf gets up pranks," says Elephant Bill. "We hadone not long ago that was always getting up mischief and poking it's trunk into somebody else'sbusiness. One day it found a fire and, being curious, touched it with its trunk. There was aterrible squeal from the frightened calf. Its mother dropped everything and ran bellowing toprotect it. All the others got excited and work stopped until they calmed down. A cow is a verycareful mother. When her calf is born she appoints another cow as foster mother. The calf standsbetween the two cows while feeding from its mother. This procedure was apparently evolved in thejungle to protect the calf against flank attack by a tiger or leopard. So when a cow has a calf,you have two cows fussing about the business and neglecting their work."

But cows expect their calves to look after themselves in the water. A cow with a calf trailingbehind will march straight into water so deep that it has to walk on the bottom of the streamwith its trunk out of the water like a periscope, while the calf swims very hard behind.

"I have seen one extraordinary incident which is proof of their high intelligence," says Elephant Bill. "That was a cow bringing a calf down a mountain stream after a cloudburst inthe mountains. The water was rising fast and the going was bad over the rapids. The cow liftedthe calf in its trunk, put it on a ledge above the high-water mark and left it there squealing.When the water had gone down the cow came back and lifted down the calf. For all their intelligence,elephants haven't got exceptional memories. Their memory is no more remarkable then dogs'. Andthey aren't afraid of mice particularly. They're more scared of jeeps."

"You know," Elephant Bill goes on, "best of all things elephants like destruction and to theman enjoyable job is throwing logs over a cliff. You'll see them drag a log to the edge of acliff and push it over. Then they lean over to watch it fall and a sort of look of satisfactioncomes to their faces. They listen for sounds of the crash to die away and scuttle back foranother log."

The elephant has quite a reputation on the Burma front of being able to do anything. One personwrote Bill asking if the elephant could be used to suck up tar and squirt it on roads. Anotherasked if they could be trained to crank stalled trucks on mountain roads near here. "But,"explains Bill, "there are limits."

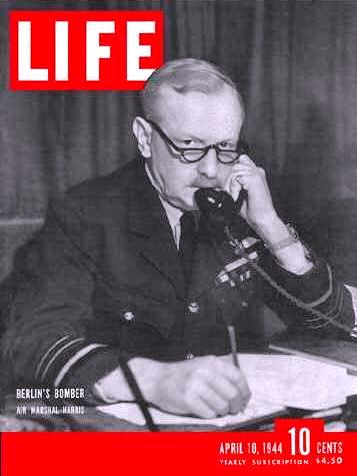

LIFE'S COVER: The theory of mass bombing of one objective is the idea of Air Chief MarshalArthur T. Harris, 51, who appears on the cover. His RAF theory has increasingly been takenover by the U.S. Air Forces. Having pleaded steadily for a thousand bombers a night, he was finallygiven them in February for first time. The air raids are ended. The air battles are on.

Adapted by Carl W. Weidenburner

from the April 10, 1944 issue.

Portions copyright 1944 Time, Inc.

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE

MORE CBI FROM LIFE MAGAZINE CLOSE THIS WINDOW