n the night of April 2, the Indian moon hung fat and full over the black waters of the Bay of Bengal.

Suddenly, roaring out of India across its white serene face, came American Flying Fortresses on a happy mission to the Japanese-held Andaman Islands.

At any rate, the leader of the flight, Major General Lewis Hyde Brereton, thought it a happy mission, for hours later when it was completed he stepped out of the cockpit of his B-17, wearing a broad and beatific grin.

"Boys," he announced warmly, "bombing Japs makes me feel damned fine!"

But this mission was notable for a more important reason than that it put Pilot Brereton into a richly cheerful humor - or even that it was the first U.S. bombing flight on record to be led by a general officer.

This mission's historic importance lay in the fact that it marked America's offensive entrance into the war in the Far East - the first time American bombers, flown by American pilots under American command and flag, had struck against the Japs in the China theater of war.

Since that day, Brereton's Indian-based bombers have hit often and hard in the Burma area.

In terms of the defense of India itself, the importance of air power is clear to everyone.

But it was not in terms of defense that General Brereton and the men in Washington were thinking when Brereton went to India three months ago.

They were thinking in terms of attack.

The men in Washington knew then that if the Allies in the Far East are ever to get off the defensive and take the offensive, the cardinal requirement was the building up of a large air force and one place in the Far East where it could be built up now is India.

Many of them still feel that, in the final analysis, the Battle for the Pacific will not be conclusively won until an air striking power has been assembled in India that can operate offensively from Chinese bases, not only to hammer at the Japs in that theater, but to strike out across the China Sea at the industrial heart of Japan itself.

Three months ago the building up of just such an air force was entrusted to a stocky, black-haired man, 5 ft. 6 in. of soldier, once called by his intimates, with conscious libel and affection, "looie, dot dope."

Dignity of rank if not age (51) has changed this gleeful nickname into simply "General Looie."

Brereton commands a U.S. Air Force with headquarters at Delhi.

In late February, when General Brereton landed in an LB-30 at Colombo, Ceylon, flying out of Java, that Air Force was nonexistent.

There were several American military missions in the Near and Far East in those days.

There were Major General Russell Maxwell and Brigadier General Elmer Adler in Cairo, Brigadier General "Spec" Wheeler in Basra, Brigadier General John Magruder in Chungking.

Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell, today Brereton's commander in chief, was still on his way from America to become Chiang Kai-shek's chief of staff.

But none of these generals commanded American troops or American combat units.

Colonel Chennault, commanding the American Volunteer Group in defense of the Burma Road, was under Chinese operational direction.

All American combat planes shipped or ferried via Africa and India were still being parceled out under lend-lease to the Allies in designated Near and Far Eastern war theaters.

The arrival of General Brereton in India changed all that instantly.

Today pilots, personnel, planes, materiel are coming in increasing quantities directly from the U.S. by ship and by U.S. ferry routes out across Africa and India, to fight under American colors.

Planes are being erected to be turned over, as required, to the A.V.G. Supplies and planes are being ferried and transported to the Chinese.

Now that Burma is gone, supplying Chiang Kai-shek's armies by air transport becomes of prime importance.

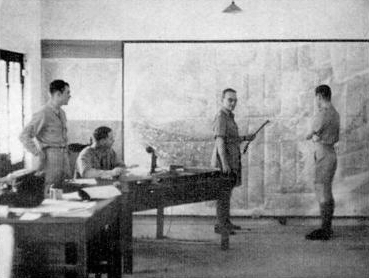

BRERETON (SEATED) & STAFF IN NEW DELHI HEADQUARTERS

BRERETON (SEATED) & STAFF IN NEW DELHI HEADQUARTERS

|

AUTHOR CLARE BOOTHE AND GEN. BRERETON IN NEW DELHI

AUTHOR CLARE BOOTHE AND GEN. BRERETON IN NEW DELHI

|

BRERETON POINTS TO ASIA MAP IN OPERATIONS ROOM

BRERETON POINTS TO ASIA MAP IN OPERATIONS ROOM

|

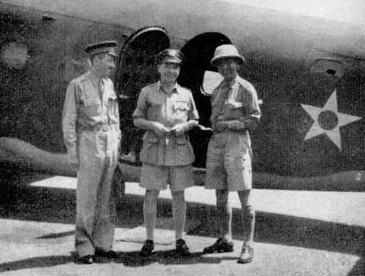

GENERAL WHEELER, BRERETON, CHINESE GENERAL MOW

GENERAL WHEELER, BRERETON, CHINESE GENERAL MOW

|

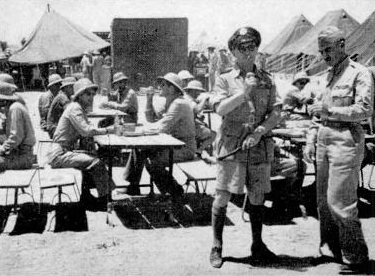

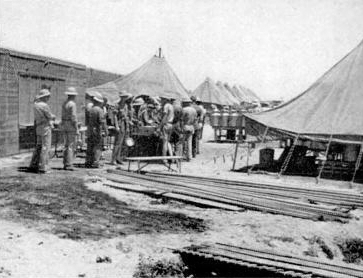

BRERETON STANDS IN OPEN-AIR MESS IN U.S. INDIA CAMP

BRERETON STANDS IN OPEN-AIR MESS IN U.S. INDIA CAMP

|

AMERICAN GROUND TROOPS IN INDIA LINE UP AT MESS

AMERICAN GROUND TROOPS IN INDIA LINE UP AT MESS

|

|

General Brereton came to his Indian command the hard way.

He came not out from Washington, but out of the besieged Philippines on the wings of a long and losing battle.

The story of his coming to India is the modern Odyssey of an American Airman.

That odyssey began on the night of Dec. 8, 1941 on the island of Luzon.

In the small hours of Dec. 8, under the wide tropical skies of Luzon, everyone at No. 9 Military Plaza in Manila was sleeping - soundly perhaps, but not peacefully.

It had been a week of dreadful conjecture and feverish preparation.

War tension had been growing for a month in the Pacific.

The armed forces of the Philippines had been on the alert at their battle stations for a week.

And on Dec. 5 a signal had come: "War is inevitable."

General MacArthur, if not prepared with what it took, was ready with what he had.

At 3:30 a.m. a telephone rang next to the bed of General Brereton, then commander of MacArthur's Far East Air Forces.

Instantly awake, as though he had been waiting up for this very call for hours, Brereton answered.

It was MacArthur's chief of staff, Richard Sutherland.

"Brereton? Awake?"

"Yop."

"Well, we've got what you've been looking for. They've just bombed Pearl Harbor. Come down to headquarters..."

In the dim shadows of his blacked-out headquarters at No. 1 Calle Victoria, among the many stanchioned regimental flags that lined his office, General MacArthur was pacing, pacing.

The hour he had both feared and faced for seven years had come.

And MacArthur knew that in modern warfare, the first blood must be drawn by or from U.S. air forces.

Half of Brereton's 36 Flying Fortresses had already been dispersed to secret fields.

But the other half lay on Clark Field, their sleek powerful forms growing more visible from the air by the minute.

Soon the red sun would be coming up, perhaps to the accompaniment of Japanese thunder - out of Formosa, cross the bay.

For four nerve-racking hours Brereton motored from field to field, seeing that all was in readiness for the attack he and MacArthur felt was inevitable.

It takes time to load bombs and you don't take off a bombing squadron the way you doff your hat to a pretty girl on a Sunday morning.

At 10:20 Brereton's planes were still loading when, from every direction, it seemed, swarms of Japanese planes came in over Clark Field: first a wave of high bombardment, then the nose divers, then the ground strafers, the Zero fighters.

When they had gone and come again, and gone and come again, three times, there lay on Clark Field, destroyed beyond repair, twelve of Brereton's precious Flying Fortresses.

And in the air battles that ensued, one complete pursuit squadron had been destroyed.

The loss in crews and pilots was another and far more tragic story.

There was little air-raid protection for Clark Field - anti-aircraft guns which had been shipped to the Philippines were in needed service elsewhere.

The crews, unable to get their planes up through the ground strafing, had sat heroically in their exposed cockpits, manning their machines guns.

After the attack a lot of them still sat there, forever motionless.

Brereton's bombers faced long odds

Plane by plane, inexorably, Brereton's forces were whittled out of the skies over Luzon.

He did what he could to offset the enemy's enormous numerical superiority.

He kept his big bombers in the air all day long, taking off at dawn, when they bombed transports and enemy landing parties, coming in only at night.

But morning, noon and night, not only were all the pursuit fields that Japs could locate bombed, but every open field was raked with machine-gun fire.

Clark Field had been taken out the day the battle began.

Radio directional finders on the Islands had been put out of business almost at once by the Japanese.

Gradually engines wore out, there were no replacements, pursuit pilots were being shot down, oxygen ran short.

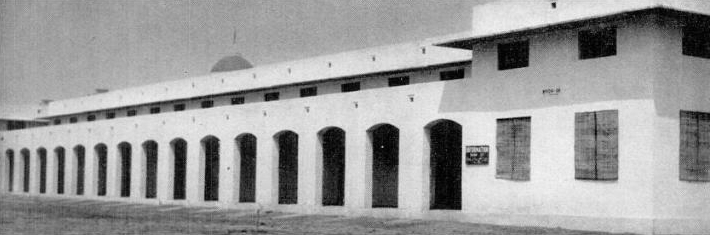

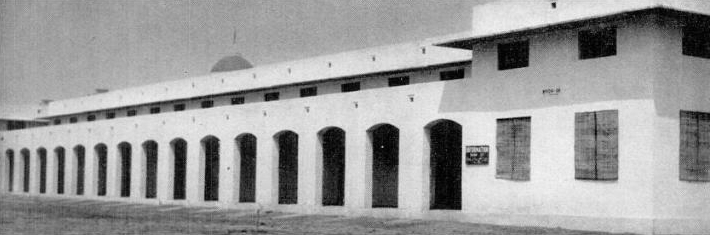

THE PLASTER HEADQUARTERS OF GENERAL LEWIS BRERETON'S U.S. AIR FORCE IN INDIA FROM WHICH HE RUNS HIS WAR

THE PLASTER HEADQUARTERS OF GENERAL LEWIS BRERETON'S U.S. AIR FORCE IN INDIA FROM WHICH HE RUNS HIS WAR

|

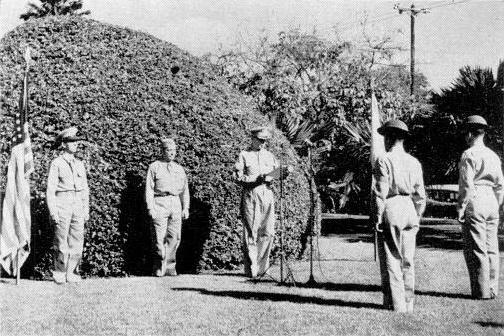

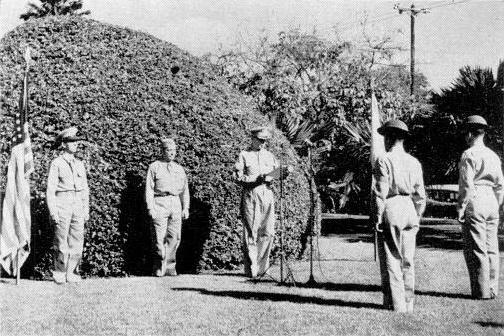

THE CREWS OF THE FIRST FLYING FORTRESS RAID ON THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS ARE AWARDED SILVER STARS BY BRERETON

THE CREWS OF THE FIRST FLYING FORTRESS RAID ON THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS ARE AWARDED SILVER STARS BY BRERETON

|

|

Brereton saw that his air force ought to be withdrawn from the Islands to some place south where it could perhaps function in their defense more effectively.

In the middle of December he drew up an estimate of the situation for MacArthur.

And MacArthur agreed that this slow annihilation of men and planes was futile.

He ordered Brereton to retire with his available planes to Australia, from where he could still operate in support of the Philippines.

Brereton, who with 130 million other Americans shares the hero worship of MacArthur, at this point offered to stay himself - and to revert to his original role of an artilleryman, on Bataan Peninsula.

It was a gallant gesture.

But MacArthur was too canny a general to accept it.

He knew that Brereton had now gotten what it takes a general to win a war - bitter experience in battle.

And he saw quite clearly that one day this experience was going to be particularly valuable - in taking back the Philippines.

At 1:30 a.m. on Christmas Day, Brereton, Major Norman Lewellyn, his A.D.C., Brigadier General Brady and Colonel Eubank, his bomber command chief, with their baggage strapped to their backs, took off for Java.

Behind General MacArthur, awarding two Distinguished Service Crosses for heroism to a Filipino and a U.S. flier in Manila Dec. 20, stands air chief, General Brereton.

Behind General MacArthur, awarding two Distinguished Service Crosses for heroism to a Filipino and a U.S. flier in Manila Dec. 20, stands air chief, General Brereton.

|

On the way they flew at an altitude of 10,000 ft.

And as they had left the ground dripping with perspiration and caked with wet mud, carrying nothing but tropical clothing, they all promptly became candidates for double pneumonia.

It was not the least miracle of that trip that, when they landed in Soerabaja, none of them even had the sniffles.

They shaved, dressed and sent Christmas cables home.

By noon Brereton was in conference with General Ilgen, local commander of the Dutch Army, as to how his remnant air force might, in cooperation with the Dutch, go on operating in defense of Luzon.

There followed for Brereton hectic trips to Bandung to consult with Lieutenant General ter Poorten, and to Darwin and Townsville to consult with the Australian authorities.

He was bombed in every Javanese city he put into for conferences.

And, as MacArthur on Corregidor, there went Brereton to the men back home urgent appeals for reinforcements via Australia.

By the time the first planes had begun to arrive across the long reaches of the Pacific, Java was already in jeopardy.

Most Javanese fields could not support the heavy Flying Fortresses.

Brereton recalls one field in Java which was entirely covered in grass.

"After a plane took off," he said, "the field looked like Meadowbrook between chukkers - with a hundred coolies rushing out to replace the divots."

The insane story had begun to repeat itself: Too little and too late - but for the first time it bore an American trademark.

In spite of the fullest cooperation of the valiant Dutch, there were not enough supplies, emergency fields, bases or ground forces to use against paratroops.

Daily, the only three Javanese fields Brereton had were attacked.

And out of captured Palembang and Makassar the Japs had begun to lambast Soerabaja itself.

U.S. pilots lacked experience

American pilots, fresh from American schools, had to be hurtled piecemeal into battles against veterans.

"The Japs poured into battle," the general says, "and we had to dribble, dribble, dribble."

At no time in the battle of Java was Brereton operating with full and battle-trained squadrons.

Whole squadrons were shot down while ferrying over the sea - with no gas left to fight or run.

Of the heroism of these green pilots, the superb stamina and gallantry of his own veterans who had flown the skies over Luzon, sometimes staying in the air ten hours a day, landing only to refuel, servicing their own planes on the field, facing as they well knew odds so vast that every day they survived was a sheer gift of a whimsical heaven - of this Brereton does not often speak now.

When he does, the tough, hard-boiled general suddenly finds he has to blow his nose so hard that in the end he must leave the room.

It's better not to speak to him at all of ground troops and crews and pursuit pilots he had to leave behind, manning machine guns on Bataan, and of the pilots he lost in the flaming skies over the China seas.

They were so young, so gay and dauntless in the face of that Yellow Death that it "just burns me up, night and day," says the General.

Brereton's own photograph of one of his four-motored Flying Fortresses tragically burning on the ground at Java's concrete-surfaced Andir airdrome at Bandung, Feb. 17.

Brereton's own photograph of one of his four-motored Flying Fortresses tragically burning on the ground at Java's concrete-surfaced Andir airdrome at Bandung, Feb. 17.

|

On Feb. 17, General Brereton and General George Brett (U.S. deputy commander in chief in the Southwest Pacific Command) met in GHQ at Lembang to discuss the situation.

They agreed it was deteriorating even more rapidly than anyone could analyze it.

No sooner had the loudly hailed ABDACOM (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command) been formed on Feb. 6 than events themselves began to dictate its dissolution.

On Feb. 24, Washington and London ordered General Wavell and the British to retire from Java to Burma and India, and the Americans to Australia.

Anticipating this situation at their meeting, Brereton and Brett reached a momentous decision, which Washington instantly ratified.

It was decided that Brett would take over what was left of Brereton's air forces coming out of Java, and that Brereton himself should proceed to India, there to begin building up an American Air Force which could one day strike at Japan through China.

Thus, on the night of Feb. 24, the very day ABDACOM was dissolved, General Brereton boarded an LB-30 out of Jogjakarta, Java, and came the next morning to Ceylon.

Two days later in Delhi, he sat down to consider his assets.

They were nothing but the faith of Washington in his judgment and, above all, his own experience and the experience of the men who had followed him from Java a few days after.

Among his staff members and combat pilots there were 14 Distinguished Flying Crosses, ten Purple Hearts and enough "silver stars" to spatter Old Glory itself - all won since the night their joint odyssey had begun in December in the Philippines.

Delhi is hot and overcrowded

Instantly upon his arrival in hot Delhi, General Brereton and his staff began to make of what was almost a self-appointed mission, and important military potential in the Battle of Asia.

He took over for his temporary headquarters a string of cement and plaster offices in the R.A.F. buildings, within a stone's throw of the Viceroy's Kubla-Khanish palace.

There, under the slow whirling punkas, he began the vast administrative job of assembling, from 12,000 miles away, fighting, ferrying and air cargo services under the American flag in India, an impossible and hopeless job, he claims, if at the other end of "the long hop" he was not being so truly guided and abetted by the Ferry Command and the War Department in Washington.

General Brereton lives in a high-ceilinged comfortable two-room suite in the swank Imperial Hotel in Delhi.

His prize possession is destined to be an air conditioning machine sent to him by General Motors officials in Bombay.

In Delhi in the summer the thermometer often stands at a temperature of 115°.

In order to secure this suite and additional rooms for his staff in Delhi, overcrowded with British military and politicos, Brereton was forced to request the Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, to requisition the rooms from British residents who rather openly resented being ousted by "those Americans."

With such complacency Brereton has small patience.

And in Delhi, in spite of the fact that it is the capital and the military headquarters of British India, complacency is unfortunately still rampant among the British, American and Indian civilian residents.

Brereton's secretary is Mrs. Dorothy Jepson, blonde wife of a Firestone Tire official.

She fines him a rupee for every British expression he uses, has collected on two "Rightos."

Brereton's secretary is Mrs. Dorothy Jepson, blonde wife of a Firestone Tire official.

She fines him a rupee for every British expression he uses, has collected on two "Rightos."

|

In Delhi far too many people still dress for dinner, give large cocktail, lawn and dinner parties and altogether live the life of the peacetime colonial.

Although there are few men fonder of a "good time" than the General, one of his first orders to his staff was a colorfully worded warning against what he called "Delhi-dallying."

He makes it a point to accept no invitations to dine out which are not "official."

But to his consternation, in Delhi this still lets him in for a lot of lawn parties with Indian nabobs, jeweled and turbaned maharajas and polo-playing British officialdom.

His aide says there is a short stormy scene every time he is forced to get out of his "bush jacket" and shorts and into a formal jacket and trousers for these functions.

He feels that he should have been allowed to say farewell to all that for good in Manila.

He is not in any sense, however, "anti-British."

When any criticism of the British military effort in the Middle or far East is made in his presence, he says sharply: "We've got no right to pass judgment.

Wait until we have faced the same problems.

We've still got to prove we can handle the headaches they've handled any better.

And on the record, except in the Philippines, where have we so far smeared ourselves with glory?

We've shown nothing yet that stacks up to the Battle of Britain."

Brereton's reputation among his own men is for being tough, hard-boiled, and a "terrific driver."

Bomber Pilot Combs tells an illustrative story of the General's "hard-boiledness," during the raid which he led over the Andaman Islands.

As they sighted their target, a transport ship, the bombardier let go.

A second later, he thrust his blonde young head up into the cockpit, chortling with pardonable pride, "Oh boy! I made a direct hit!"

Whereupon General Brereton instantly clapped his square hand on the young bombardier's curly head, and shoving him back down into the bombpit, snarled, "Get back down there you little so-and-so and make another!"

Two weeks later, when Brereton was pinning silver stars on the boys who had taken part in this raid, he was seen to wink heavily when he pinned the decoration on the chest of the young bombardier.

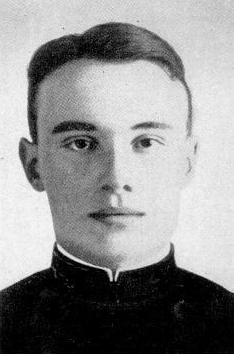

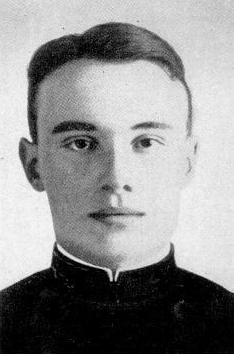

At Annapolis, rambunctious Brereton marked time waiting to get into the Army.

At Annapolis, rambunctious Brereton marked time waiting to get into the Army.

|

His brother is Captain William D. Brereton, now U.S. naval attaché in Argentina.

His brother is Captain William D. Brereton, now U.S. naval attaché in Argentina.

|

|

Brereton has an extraordinarily rich vocabulary, swearing in three or four languages.

To this gift for cursing is added an appropriate temper, and the first ten minutes of his morning staff meetings are generally devoted to a brimstone coverage of staff delinquencies.

The rest of the time he makes cool and thoughtful sense.

He thinks well and rapidly on his feet, talks in a rasping, somewhat "tough" voice, though using a vocabulary which while not exactly "literary" is far more flexible and rich than is usually associated with the speech of professional American soldiers.

His conversation is remarkable for another reason: he seldom uses the pronoun I - preferring to refer to himself as "Lewis Brereton."

Yet he is no brass-hat martinet.

Famous already is the staff conference at which, having "eaten the ears off" three junior officers for work left undone the previous day, he rose, walked to the door and thundered, "Work, work - night and day, that's the only way we're going to win this war!"

and then suddenly turned on his heel and snapped, "And another thing - who the hell forgot to reserve us that tennis court between 5 and 6 last evening?"

He confesses to one non-military ambition in India.

"I'd give my eyeteeth to shoot a Bengal tiger."

He has been asked a half-dozen times to do so by Indian nabobs, but has refused.

"Can't risk it," he says, "If I go tiger-shooting this week, the Japs might get Brereton-shooting next week..."

Lewis H. Brereton was born in Pittsburgh, June 21, 1890, the second son of William Denny Brereton, a brilliant and successful mining engineer, and a fourth-generation American of Irish and English ancestry whose forebears had fought in every war since the French and Indian Wars.

His mother, Helen Hyde, was in one way a rather remarkable woman.

A middle-class English girl of High Church convictions, she displayed few of the strait-laced characteristics associated with a mid-Victorian Episcopalian English background.

Gay, fun-loving, indulgent, she made the Brereton home in Annapolis, Md. a rendezvous for all the young people in the neighborhood.

From his mother Lewis inherited his merry party-loving streak, and from his father his quick analytical mind, his sense of humor and his choler.

Describing what manner of man his father was, the General says, "Well, whenever my brother Bill and I get together our first drink is to "the old man."

After attending St. John's College at Annapolis, Lewis entered the competitive examinations for West Point and Annapolis.

Though his preference was the Army, coming out second best in the exams he had to take "what was left" - in this case the Naval Academy which he entered in 1907.

His brother Bill, today naval attaché in Buenos Airies, graduated in 1908.

During Lewis' four years in the Academy he did not, it seems, overly distinguish himself except, as he says, "by spending and unusual amount of time in confinement" and having the best time that any Annapolis cadet ever had.

To date, Brereton's class of 1911 has not proved itself one of the notable classes.

It does not boast even one admiral.

"But give 'em time," Brereton says, "the lads are still young."

By a strange coincidence its most distinguished alumnus turns out to be Two-Star Soldier Brereton.

Brereton started with the Navy

A peculiar military situation prevailed at the time Lewis Brereton graduated from Annapolis.

In 1911 there were some extra ensigns graduated while, owing to one of those all-too-rare periods in America of Army expansion, there was a shortage of second lieutenants.

In the fall of 1911 Lewis happily resigned from the Navy and entered the Army, a shavetail coast artilleryman.

He considers it the most natural thing in the world that a year later when the Signal Corps became interested in aviation he transferred to the infant air wing of the U.S. Army.

For the next few years he flew around in a Curtiss pusher.

In October 1917 he went overseas with 80 other air officers under the command of Brigadier General Benny D. Foulois.

He served first with a French squadron near Verdun.

In March 1918 he took command of his own squadron, the Twelfth Observation Squadron.

In was during these days that he won the Distinguished Service Cross and the Purple Heart.

Asked how he got the former he says, "Trying like Hell to get home when some Huns got in the way."

He does not add how many Germans he shot down to reached his cherished objective.

Of the Purple Heart awarded to him when he was shot down at St. Mihiel he says, "You rate it for being dope enough to intercept an enemy bullet."

Of his other decorations, the Legion of Honor, the Croix de Guerre with three palms, the Victory Medal with six stars and a number of others from Allied governments, he says, "There weren't enough of these things handed out - everybody deserved them."

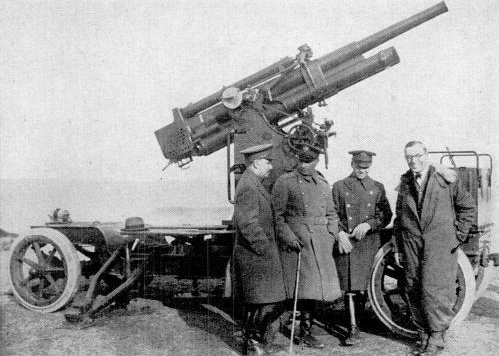

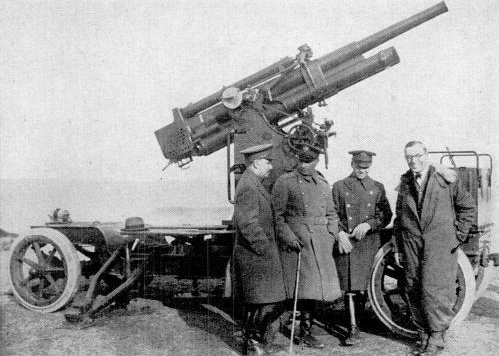

"Billy" Mitchell (with cane) at 1925 aircraft demonstration at Fort Monroe, Va.

Young Brereton is smiling at right of him.

At extreme right is a congressman in flying suit.

"Billy" Mitchell (with cane) at 1925 aircraft demonstration at Fort Monroe, Va.

Young Brereton is smiling at right of him.

At extreme right is a congressman in flying suit.

|

Young Brereton was that rarest of combinations: a gallant and daring fighter and a man with a "staff mind."

In late July of 1918 he became chief of aviation of the First Army Corps under General Hunter Liggett.

Until February when he returned from the Rhineland with the Army of Occupation, he was on the late Billy Mitchell's staff.

Asked by an insistent interviewer if he remembered any long, fascinating and prophetic conversations with Billy Mitchell on the subject of "airpower in the future," Brereton replies tersely, "Plenty."

Asked "And what did you say?" he answers with an enormous grin, "Who me? I said, 'Yes sir' and 'No sir.' Mostly I just listened."

Years later Brereton was one of Mitchell's three associate counsels at his trial.

Brereton, questioned about this unhappy occasion, puts on his "dead-pan" face, his large brown eyes normally snapping with life grow dull and he allows his eyelids to fall over them wearily.

He does not like to discuss it.

Pressed, he explodes, "Mitchell was guilty, all right, of the charge he was ostensibly court-martialed on, insubordination - an attitude calculated to cause the public to lose faith in the judgment of high Army officials.

He believed that military men who didn't realize the importance of the air had no right to breathe it in America.

But of his air-mindedness, time has wholly vindicated him..."

With the end of the war the young flier got a pleasant new assignment.

From 1920 to 1922 he was air attaché in Paris under Ambassadors Myron Herrick and Hugh Wallace.

He learned to speak fairly voluble French with a good Parisian accent, acquired a taste for fine wines and good food which has never deserted him.

In 1922 Brereton returned to the U.S. to command the Third Attack group at Kelly Field.

In 1913 he had married Miss Helen Willis of Milwaukee, by whom he has two children - a son, Lewis Brereton, Jr., now practicing law in Charlottesville, N.C., and a daughter Betty, married to Lieutenant Charles Lord, a naval aviator.

In 1929 the Breretons were amicably divorced and in 1923 the General married a girl 16 years his junior who is now living in San Antonio and answers to the cool and delightful name of "Icy."

The years between 1922 and 1940 were not otherwise eventful for the man who at 28 had been a lieutenant colonel.

After he returned to the U.S., he also returned to being a major, and a major he stayed all through the 15 years when he was instructing at the Air Corps tactical school at Langley Field, commanding the second bombing group, studying at Leavenworth, instructing in the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, and when sent out by Benny Foulois to do a four-year Panama tour in command of the panama Air Depot and France Field.

In 1935 he was again made a lieutenant colonel.

By the outbreak of World War II he had been made a full colonel.

Now it became apparent that this galvanic, laughing man with the sharp and sometimes overly frank tongue, whose "cockiness" and individuality had often bordered on the dangerous fringes of insubordination, was nevertheless one of the few highly qualified U.S. experts on aerial bombardment.

In 1939 it was half suspected that aerial bombardment was a tactic that somewhat interested the Germans but by the time of the blitz it became painfully evident that it was going to be their all-year-round favorite outdoor sport for the duration.

Brereton was upped to a brigadier.

In July 1941 the next step followed, and Brereton was given his second star, with command of the Third Air Force at Tampa, Fla.

In November he was sent out to command Lieutenant General MacArthur's Far Eastern Air Force.

When the General left by Pan American Clipper out of San Francisco he was a "pure soldier." one of the few generals in the U.S. Army who had never "gotten mixed up in Washington politics."

Recently on the Burma-China front at Toungoo, he comforted a disgruntled brother officer, saying, "There are lots of fellows who envy you boys out here.

Do you realize that geographically you're as far away from Washington, D.C. as it's possible to get?"

When Brereton landed in the Philippines Islands he was "pure" in another sense too.

Like nine out of ten generals he was still totally innocent of the true nature of aerial combat battle, in spite of the fact that he had had a distinguished World War I flying record.

But the war in the air in 1918 and the air in the war now, Brereton would be the first to tell you, are totally different things.

Since Dec. 8, 1941 Brereton claims he has learned more about modern air war first-hand than he learned in all his 51 years' experience.

When General Brereton landed in India from java, he firmly resolved never again to commit his forces to battle until he had built up sufficient strength so that they would have an equal chance against the enemy.

"No more dribbles for me." he swore and then added with a grim laugh, "Though if things get too hot for the A.V.G. and R.A.F. I may have to leak a leedle."

But today, whether Brereton's bombers are being "committed in force" in the Battle of India or whether they are "leaking a leedle," General Looie has not changed his mind about one thing - that his odyssey has just begun because, he says, he is really on his way to the Philippines and Tokyo.

|

After forming what would become the 10th U.S. Air Force, organizing the 12,000 mile supply line from the United States and shortly after this article appeared, General Brereton was transferred to North Africa along with the best bomber aircraft and crews then in India, in response to the German threat to the Suez Canal.

|

LIFE'S COVER: The plain and simple portrait of Hedy Lamarr as a pretty Portuguese in Tortilla Flat indicates a new phase in her career.

Since she came to Hollywood from her home town of Vienna in 1937, Hedy has been groomed for glamor roles.

But now, discovering that she can get by on her acting ability, MGM has booked her for peasant parts in Dragon Seed and White Cargo.

Meanwhile, Hedy is busy with plans to marry her third husband, Movie Actor George Montgomery.

General Lewis Hyde Brereton, commander of the U.S. Air Force in India, was youngest major general in U.S. Army. He arrived in India with a blanket roll called "The Baby," in which he had saved from the fall of Java $250,000 to pay U.S. troops. The priceless asset of Brereton and his staff is that most of them have already fought the Japs on several arenas.

General Lewis Hyde Brereton, commander of the U.S. Air Force in India, was youngest major general in U.S. Army. He arrived in India with a blanket roll called "The Baby," in which he had saved from the fall of Java $250,000 to pay U.S. troops. The priceless asset of Brereton and his staff is that most of them have already fought the Japs on several arenas.

Behind General MacArthur, awarding two Distinguished Service Crosses for heroism to a Filipino and a U.S. flier in Manila Dec. 20, stands air chief, General Brereton.

Behind General MacArthur, awarding two Distinguished Service Crosses for heroism to a Filipino and a U.S. flier in Manila Dec. 20, stands air chief, General Brereton.

Brereton's own photograph of one of his four-motored Flying Fortresses tragically burning on the ground at Java's concrete-surfaced Andir airdrome at Bandung, Feb. 17.

Brereton's own photograph of one of his four-motored Flying Fortresses tragically burning on the ground at Java's concrete-surfaced Andir airdrome at Bandung, Feb. 17.

Brereton's secretary is Mrs. Dorothy Jepson, blonde wife of a Firestone Tire official.

She fines him a rupee for every British expression he uses, has collected on two "Rightos."

Brereton's secretary is Mrs. Dorothy Jepson, blonde wife of a Firestone Tire official.

She fines him a rupee for every British expression he uses, has collected on two "Rightos."

At Annapolis, rambunctious Brereton marked time waiting to get into the Army.

At Annapolis, rambunctious Brereton marked time waiting to get into the Army.

His brother is Captain William D. Brereton, now U.S. naval attaché in Argentina.

His brother is Captain William D. Brereton, now U.S. naval attaché in Argentina.

"Billy" Mitchell (with cane) at 1925 aircraft demonstration at Fort Monroe, Va.

Young Brereton is smiling at right of him.

At extreme right is a congressman in flying suit.

"Billy" Mitchell (with cane) at 1925 aircraft demonstration at Fort Monroe, Va.

Young Brereton is smiling at right of him.

At extreme right is a congressman in flying suit.