The battle of India, even when there was active war against the Japs in Burma and China,was a battle of boredom, a war of supply and of waiting with occasionally an air raid and always the strangenessof the country to remind you that you were overseas because there was a world conflict raging.The story that follows is a record of part of that war of supply, the slow, unlazy progress of a GI barge-towing tug. The two diesel engines on River Tug 810 churned quietly, just fast enough to keep her in place as she waitedfor a freighter to come through the locks at the Calcutta Basin. On her starboard side she was towing a loaded bargewhich the deck hands had just lashed tight. This was 810's first voyage in Indian waters, and this was to be her maiden trip on duty along the Ganges Rivergasoline run. She'd been used against the Japs in the Aleutians, and the GI sailors who manned her were battleveterans, too - men who had served on Guadalcanal, in Africa and Sicily, or with Merrill's Marauders in Burma. There were eight of these GI rivermen. Men and ship were playing a new role in this war, serving behind the linesagainst the Japs, yet battling an enemy of their own. Their enemy was the Ganges River with its delta tributarieswhich rivermen claim have the fastest running tides in the world - tides and swirling currents which have probablyswallowed the bodies of more rivermen than any other of the world's great waterways. Three of the crew sat around the galley table. Up to that time their conversation was about the river, its currents,the tug they were shipping on, the load of high octane they were to carry. Deckhand T-5 Paul Sallee of Newport, Ky.,changed the subject into the familiar GI channels - women. He made some remarks about the women of India and thendrifted into a narrative about how he finally succeeded in winning a WAC wife. The pre-shoving-off tension vanished as the men listened to him tell of his courtship and finally of his marriage.They laughed when he came to the part about his honeymoon."Then I got cheated out of that," he said. "She goes and gets herself restricted to the company area." A sharp blast on the tug's horn ended the redheaded deck hand's discourse. The 810 was underway, and the menwent out on deck to watch her pass through the locks. They watched the busy ship traffic in the Calcutta Basinslowly slip behind them as the 810 chugged through. Then they settled back to rest, to face three days of slow,grinding travel up to their first stop on the Hooghly River. The 810 was a pretty good-sized ship and normally carried a crew twice the size of the one now travelingon her up the muddy, turgid, Hooghly. The eight men aboard knew they were in for a grueling time, doing twice asmuch work as normally called for and pulling watches twice as frequently. It might not be so bad on the slow,lazy Hooghly, but after they passed Diamond Harbor, in the Bay of Bengal, then the job would get tougher. Still,the Hooghly could cut up a bit, too, when the monsoon hit. On the third night 810 tied up, and early the next morning it was still dark when the oilers and deck handsrolled out of their sacks to hit the deck. Fuel for the long, tedious journey to the gasoline run had to be takenon. What should have been a half-day's detail had run into two. The loaded barge was left a few miles down river, and the 810 pulled up to a military jetty to get her oil supply. By mid-morning about 1,000 gallons had been siphoned into the tug's after-tanks and the fueling appeared to beprogressing according to schedule. But the bottom fell-out of the schedule a half-hour later when the crew found itself embroiled in a rank-pullingargument which, they said, was a common occurrence along India's steamship lanes. The RT 810 tangled with a 15,000-ton freighter which wanted to fuel up first. The freighter had the harbormasteraboard and won the argument over the 90-ton tug easily. Oil was shut off temporarily from the RT 810 while thefreighter fueled. The RT 810 finished taking on fuel by the next morning through a makeshift oil hose tapped into the regularline and strung across the barges to which she was tied. There was little time for the crew to catch up on sackhours, and there was a long list of small but important things to be done on the 810. The engine's pumps had to becleaned out, fender ropes needed repair, the spotlight for night runs was out of order. After the fueling, the 810 went back to pick up the barge she had left down-river, and by that night she wasrunning in the open waters of Diamond Harbor. Her nose was headed across India's sundarbans, long fingers of parallelrivers that wriggle their way into the Bay of Bengal. These were new ways for the 810 but not for her crew, most of whom were old hands at pushing gasolinethrough these waters with sea mules. Two GIs had died in these waters. On the Ganges itself no one could ever be sure that a sea mule would bringits tow load of gasoline to the planes that carried some of the gas over the Hump into China. The men called it success just to keep their ships and barges pointed in the right direction when the tidewas running high. Keeping a vessel and its tow under control even though there is no headway was considered a goodjob of work. Pfc. Sam Minor of Chicago, an oiler on the 810, had been one of the crew members on a sea mule which was whippedashore en route by wildly running waves, stirred to a frenzy by high winds. Minor and the rest of the crew were strandedfor seven days, sealed off from rescue by huge, twisting whirlpools that would have spelled disaster for any craftunder the size of a freighter. The men lived on a half-case of C-rations because there was no craft on hand able to get in close enough to them.The bigger ships could approach only so far before being caught by the treacherous waters, and smaller craft were bobbedaround like matchsticks. Minor and his mates were picked up beaten and weak when the river finally calmed down. The threat of being stranded like this was always present. Those who took seriously ill on the gas run facedheavy odds at reaching a Calcutta hospital. They had to be carried long distances along the river to a railhead beforegetting better transportation. Long hours, poor meals, sleepless nights and the aching backs that come from long tussles with rampaging riverscrusted the men with a layer of toughness. ratings were off and on with traffic-light frequency, but the job gotdone. Company records show that the monthly average of gasoline pushed to its final destination never fell below aperch up in the millions of gallons. On the RT 810 the holder of the highest civilian maritime rating held the Army's lowest. He was Pvt. William McNallen of Portland, Ore., who had the papers of a chief engineer for inland waters and was licensed as a secondassistant steam engineer. He was the 810's chief assistant in the engine room. The crew of the 810 on this trip were about half divided in shipping experience. Minor, McNallen, and Pvt.Kenneth Niemals of Duluth, Minn., a deck hand, were old hands. Sallee had once worked on a pleasure yacht, while Pvt.Simmons Fonzo of Beaufort, N.C., had had some experience on a river dredge. The first mate, Sgt. LeRoy Alford ofConcordia, Kans., was strictly a landlubber before he joined his harbor-craft outfit. Two civilians completed the crew. The skipper was Army Transport Service Capt. Seek S. Brandon of Detroit, Mich.The Indian river pilot was Ahmed Ali Ashref. There were several Indian pilots, who relieved each other along thecourse, each with his own special knowledge of the immediate waters. When Diamond Harbor was finally reached, it threw the first curve at the 810. The tide was running fast, and,with the barge she was towing instead of hugging to her side as before, the 810 couldn't muster enough strength tomatch the current's speed. Her engines ran at full speed for four solid hours, but the best the 810 could do was tokeep the tide from pushing her back. She didn't move 10 yards in all that time. She was stuck in a lane of ocean freighters that blew so many warningsignals it sounded like New Year's Eve. By nightfall she was able to make some headway but only to emerge from one beating and head right into another. A storm hit the 810. Waves picked her up and picked up her barge and tossed both around like so much cork. Oilers and deck hands worked frantically to sink an anchor where it would hold. The 810 drifted so fast that the lightanchor hung out at the end of its line like a plug on a trolling line, almost horizontal, never touching bottom. McNallen had the Diesels turning at full speed to keep the tug under some control, but only pure luck kept herfrom crashing into several other ships in the same predicament. Through the darkness of the storm First Mate Alfordsaw that the barge was listing heavily to port. She was filling up and sinking fast. There was no way to anchor the barge, and allowing it to float and pitch freely in the stormy waters wouldhave endangered other craft that might steam into her path. But it was this chance against the lives of the crew.Sallee cut the barge loose, and in a few moments it ran out of sight into the turbulent blackness. The crew put in long hours before the storm subsided, but still there was not time to rest. They stayed at theirstations while the 810 played a hide-and-seek game for the runaway barge which might possibly be still afloat. After an hour's search, it popped up into the beam of 810's searchlight. The tug approached it easily and workedher way around to the stern. Deck hands lashed it to the tug's bow in a position for pushing. They stood by with fireaxes ready to chop the barge loose again if it started to sink completely. The searchlight probed the darkness, catching in its light millions of India's insects which blanketed the beamlike heavy snow, while the crew and especially the Indian river pilot looked for a beaching spot. In sign languagethe pilot indicated an approachable sand bar, and Alford, at the helm, signaled the engine room for full speed ahead. The engines turned up, and at the top of this burst of speed to the banks Sallee and Niemals let go with theiraxes, cutting the heavy lines and letting the barge coast to its resting place on the sand bar. The barge was left behind for salvage, and the crew settled back with great relief at the prospect of completing their run without a barge to be nursed along. In three more trouble-free but dull days the 810 arrived at the Ganges portwhich was to be their home base on the gasoline run. There she was to go into dry-dock for major repairs and finalfittings before starting the regular run. The delay meant at least a three or four day rest for the crew. Down in their compartment they made cracks about joining the Infantry. The mate hit his sack, wearily saying:"When I get through with this, I'll never get on another dammed ship as long as I live."

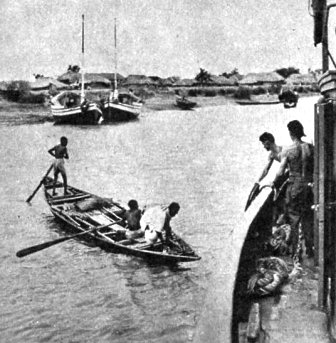

While the fighting war was still going on in Burma and China, GIs kept military supplies moving by tugboat along India's waterways. A Ganges river pilot, in the bow of the Indian canoe, gets ready to come aboard the RT 810

A Ganges river pilot, in the bow of the Indian canoe, gets ready to come aboard the RT 810 Indian men and women coolies haul tins of oil to a barge while a river tug waits to take on fuel.

Indian men and women coolies haul tins of oil to a barge while a river tug waits to take on fuel. T-5 Sallee straddles a line on an anchor buoy to attach more line, holding the tug against the tide.

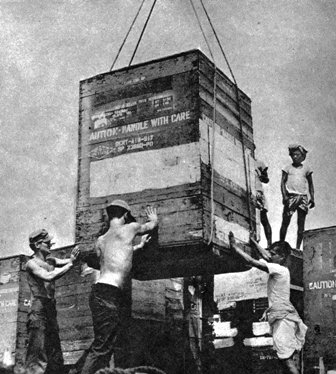

T-5 Sallee straddles a line on an anchor buoy to attach more line, holding the tug against the tide. The GI river men have to load and unload at the docks as well as man the boats. Here coolies help them to unload crates packed with airplane motors.

The GI river men have to load and unload at the docks as well as man the boats. Here coolies help them to unload crates packed with airplane motors. The RT 810 (left) comes alongside the RT 807, which has jammed one of her rudders.The GI crewmen helped each other out and exchanged the latest word.

The RT 810 (left) comes alongside the RT 807, which has jammed one of her rudders.The GI crewmen helped each other out and exchanged the latest word.

Story by Sgt. JUD COOK - YANK Staff Correspondent

YANK - The Army Weekly - November 30, 1945

Adaptation Copyright © 2005 Carl Warren Weidenburner

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE

ORIGINAL PAGES FROM YANK MORE STORIES FROM YANK

CLOSE THIS WINDOW