Scroll down to view...

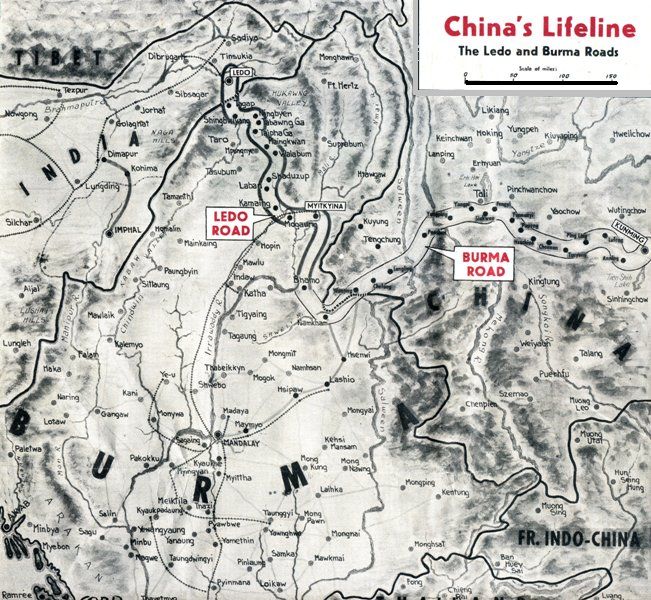

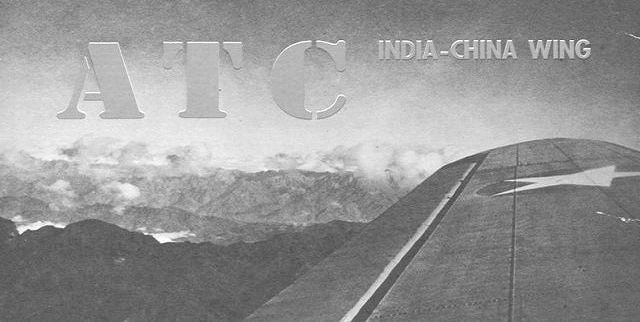

Just after dawn on that morning of Apr. 9, a battered and worn Douglas DC-3 transport plane took off from a jungle airfield in Assam, India, and climbed laboriously over the 14,000-foot peaks of the Himalaya Mountains, which separate India from China. The aging plane was loaded with 100-octane gas intended for the B-25s of Brig. Gen. (now Maj. Gen.) Jimmy Doolittle's Tokyo raiders, if they landed safely in China. Pilot of the DC-3 was Lt. Col. (now Brig. Gen.) William Donald Old of Uvalde, Tex. Old's flight had little immediate effect on the course of the war in the Far East. But the long-range possibilities of that first aerial supply trip across the Hump - the name U.S. airmen have given the Himalayas - were not lost on a group of U.S. Army officers in India. They saw that this new air route was more than the last hope of keeping China in the war until the vast potential of Allied power could be concentrated in the Far East. They realized that some day it might actually surpass the supply capacity of the winding, tedious Burma Road. They were right. American planes are now carrying more military supplies, by actual weight, to China than were hauled over the Burma Road in any average month during the two years before its capture by the Japs. Those supplies are being transported by a constantly increasing fleet of U.S. two and four engine airplanes, operated by the Air Transport Command's India-China Wing between bases in Assam and Yunnan Province. Gasoline and bombs used by Maj. Gen. Chennault's Fourteenth U.S. Air Force are flown into China by ATC planes. Weapons carriers, 2½-ton trucks, jeeps, 4,000-pound ack-ack guns, medical supplies, food and clothing for both Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell's U.S. forces in China and the Chinese Army itself are ferried through the skies by this huge cargo-carrying operation. Dwarfing any commercial air-line operation in history, the India-China Wing's 24-hour-a-day ferry service over the Hump hauls more cargo then the combined pre-war freight carried by all U.S. civilian air lines. It has more pilots and operates more planes than America's three largest commercial lines did up to December 1941. It even has its own "shuttle run" from the United States to Assam. Planes bring necessary spare parts and other high-priority supplies direct from Patterson Field, Ohio, to the ATC bases in northeastern India. The shuttles make the 15,000-mile trip in a few days, stopping only for fuel and new crews en route. Officially the flyers of the ATC are not combat men; they are only freight crews. Yet they have flown the most dangerous air route in the world, bucking weather, mountains and Japs in daily defiance of the law of averages. Some of them have died carrying out their missions. Others have suffered injuries that will cripple them for life. All of them have done a job that rates right up alongside Guadalcanal and Salerno. Weather and mountains are the principle headaches. Monsoons that ground the Jap air force in Burma don't stop the ferry crews flying the Hump. Freezing overcasts put three inches of ice on their windshields and two inches on their wings. The pilots have to fly blind when snow static cuts off radio communication and leaves them lost for hours. Sudden storms and downdrafts haunt them. Towering mountain peaks bend their radio beams miles off, so the pilots have to correct navigational drifts many degrees, and force the overloaded planes up to altitudes exceeding those at which they were designed to fly. Even so, there is always the threat of a mountain wall looming up still higher ahead. A forced landing in this jungled and mountainous terrain is a million-to-one shot. Those odds were lengthened when the Japs offered the head hunters 300 rupees for every GI head. Finally, the ferry crews face the constant threat of being jumped by roving Jap fighter patrols, packing a heavyweight punch of firepower; against this, the ATC transports have only tommy guns for protection.

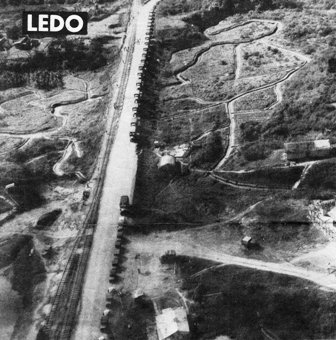

Col. (now Brig. Gen.) Caleb V. Haynes of Mount Airy, N.C., took command of the ferry service late in April 1942 when U.S. Army transports arrived to supplement the Pan-American ships then on the route. All Burma was about to fall into Jap hands. The transport crews were called on for double emergency duty. After unloading their cargoes of supplies for the Flying Tigers and the retreating Chinese Army, the planes stopped at Lashio and Myitkyina to pick up loads of Burma refugees. In the 10-day period before Lashio and Myitkyina fell to the Japs, 3,608 evacuees and 623 Chinese and British wounded soldiers were ferried to safety in India. DC-3s normally carrying 26 passengers were loaded with almost three times that number, On one trip Capt. Jake Sartz carried out 75 evacuees. Maj. Gen. Chennault himself was flown out of Loiwing in a ferry plane piloted by Brig. Gen. Old, when the Jap Army was only a few miles away. Food for Lt. Gen. Stilwell's party on its retreat from Burma was dropped by Brig. Gen. Haynes from a DC-3 that was jumped by Jap Zeros on the way back to its base. The U.S. plane escaped after T/Sgt. Ralph Baldridge, the radio operator from Wynnewood, Pa., and Sgt. Bob Mocklin, the crew chief from Royalton, Pa., had emptied their tommy guns at the enemy fighters. The entire Burma evacuation was accomplished without the loss of a single ferry plane, thanks to the one-man pursuit force activities of Col. Robert L. Scott Jr. He kept the Japs off the tails of the ferry planes by bombing enemy bases and intercepting enemy patrols in his lone P-40. Keeping the transport planes in operation during the monsoon months of 1942 was a desperate struggle. Not only the weather but lack of spare parts and reserve planes plagued the Assam-China-India Ferry Command, as it was then known. One crash put four grounded planes back in the air when the damaged ship was cut up and its parts distributed. Minor repairs were even made with adhesive tape and paper clips. A shortage of mechanics was another drawback. Truck drivers and cooks double in brass as mechanics and maintenance men. At one time, one field had only nine mechanics to take care of 15 planes. They worked an 18-hour daily schedule until reinforcements arrived. On Aug. 1, 1942, the ferry service was made part of the Tenth Air Force and renamed the India-China Ferry Command. Under Maj. Gen. Clayton L. Bissell, work was started on several new airfields in Assam, and the pilot strength was gradually increased. Several former civilian air-line pilots arrived to take over the ferrying jobs. They included United Airlines' Capt. Dick Bechel of Los Angeles, Calif.; Capt. John Payne of Paducah, Ky., and Lt. Richard E. Cole of Dayton, Ohio; TWA's Capt. Bill Sanders of Kansas City, Mo., and Pennsylvania Central's Capt. Lester Musgrove of Grand Rapids, Mich. Cole had been Brig. Gen. Doolittle's co-pilot on the Tokyo raid. Payne was the first pilot to make a night flight across the Hump. It was done entirely with instruments, and the landing in China was made with no field lighting except smudge pots. Night flights across the Hump are now routine. The enlisted crew chiefs and radio operators on the Hump planes also played an important part in the ferry route's development into a comparatively safe flying operation. The lessons they learned under what were probably the world's worst flying conditions have become gospel for later crewmen, who have had to cope with the same dangers. Among the pioneers were M/Sgt. Bud Gleason of Cleveland, Ohio; S/Sgt. Frank Ruth of Canton, Ill.; S/Sgt. Red Jones of Ravenia, Ky., and S/Sgts. Max Sharp, Johnny Shump and James W. Smith, all of Dayton, Ohio. In those early days, the ferry planes took cargo over and brought soldiers back. The return loads were made up of 30 to 40 Chinese Army fighting men, brought to India to be drilled in American tactics and equipment at Lt. Gen. Stilwell's Chinese-American training center. Those same Chinese troops are now driving the Japs from northern Burma to open another supply route from India to China, the Ledo Road.

In December 1942, the Hump ferry route was made a part of the globe-circling route of the Air Transport Command. It was renamed the India-China Wing and put under Col. E.C. Alexander. Several C-46s and C-87s arrived to supplement the DC-3s. Their larger freight capacity immediately boosted Hump tonnage totals. The C-46s were shipped to India before they had been fully tested in the States, and they soon developed several "bugs." That threw increased pressure on the overworked mechanics. A shortage of transport pilots threatened to offset the increased number of planes assigned to the route. The ATC set up its own transition school in India where several single-engine pilots were trained and pressed into ferry service. Today, under the command of Brig. Gen. Earl S. Hoag, the Hump ferry route is a typical U.S. assembly-line operation. Cargo planes fly a round-the-clock schedule. Some make three trips daily over the 550-mile route from Assam to China. Each plane must radio its engine status to its destination a half-hour before landing on the return trip so servicing facilities and a new crew will be ready to take over immediately. Despite these improvements, the Hump run is still the most hazardous air route in the world. A special ATC rescue squadron has been formed to save crews and passengers forced to bail out over the Hump. Rescue planes stand by on a 24-hour watch, ready to take off it word comes that a plane has crashed or been shot down. As soon as the survivors are located, the rescue plane drops medical supplies, maps, food, rifles and signal panels. The panels are used in patterns on the ground to spell out a message notifying the rescue ship whether anyone is seriously injured. In such a case, a flight surgeon and enlisted medical soldiers parachute to the spot to give immediate aid. The plane maintains contact with the party as the men make their way back over the jungle peaks of the head-hunter country. Capt. John Porter, 26-year-old organizer of the rescue plane unit, has been missing since his mercy ship was believed to have been jumped by Jap interceptors. Porter once destroyed a Jap Zero from his own transport plane. Spotting a Jap pilot sitting on the wing of his parked plane at a remote jungle airstrip, the captain zoomed down and killed him with a Bren gun, then strafed the Zero until it burst into flames. Walking back from a Hump ride is not an uncommon experience. It's been going on since November 1942, when Lt. Cecil Williams of New Cumberland, Pa., and Cpl. Matthew Campanella of Hammonton, N.J., first bailed out of a transport lost in a storm coming back from China. They returned 23 days later. Their endurance record was bettered by three days in August 1943 when 20 passengers and crew of a China-bound ship jumped to safety after the plane's motors failed. Twenty-six days later the party, including Eric Sevareid, CBS correspondent, reached a U.S. air base. But exclusive rights to the story to end all stories of guys who walked back from a Hump ride belongs to 1st Lt. R.E. Crozier of West, Tex., and his four ATC crew members. Driven off course by rough weather while returning from China on the night of Nov. 30, 1943, Crozier flew on instruments for two hours. Radio contact with U.S. bases in Assam could not be made and the horizon was blotted out by hazy weather. When mountain peaks suddenly showed through the "soup" on both sides of his plane, with the altimeter already reading 17,500 feet and the fuel tanks almost empty, Crozier gave orders to abandon ship. It was 2200 hours. The five Americans adjusted their parachutes for the first jump any of them had ever made. Crozier went first, followed by Flight Officer Harold J. McCallum, co-pilot, from Quincy, Mass.; Cpl. Kenneth B. Spencer, radio operator, from Rockville Centre, N.Y.; Sgt. William Perram, engineer, from Tulsa, Okla., and Pfc. John Huffman, assistant engineer, from Straughn, Ind. Minutes later they landed in the forbidden country of Tibet, 60 miles from the holy city of Lhasa. The first English-speaking person the Americans met was a Burmese monk. The Tibetans, who had never seen an American, crowded around the five airmen, gaping at them and tugging at their clothing. They gave the Yanks boots, fox-fur coats and fur-lined caps as protection against the 20-below-zero weather and invited them to sleep in their crude mud huts. After 10 days in the primitive town of Tsetang, never visited by any American before, the Yanks began a long trek back to India. Mule pack transportation had been arranged for them by the Oxford-educated Tibetan foreign minister. In true Ronald Coleman style, the U.S. soldiers made their way over the narrow, snow-covered mountain trails that wound tortuously among 25,000-foot peaks. Swirling snow lashed them as they plodded on. The only signs of civilization along the way were mud huts, spaced at intervals of a day's travel. At night, the airmen slept on mats on the floors of the huts, with fur skins as blankets. They ate mutton, rice and yak milk. High altitudes and sub-zero weather limited daily travel time to five hours, but by changing mules every two days, the Yanks were able to cover 30 or 35 miles daily and to complete the two-month trip in just 30 days. Crozier and his crew are the first airmen ever to fly over Lhasa and are among the very few Americans who have ever seen that holy city. The Air Transport Command is really going places these days when some of its men even land in Shangri-La.

|

March 10, 1945 edition.

|

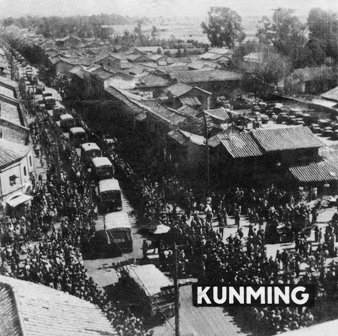

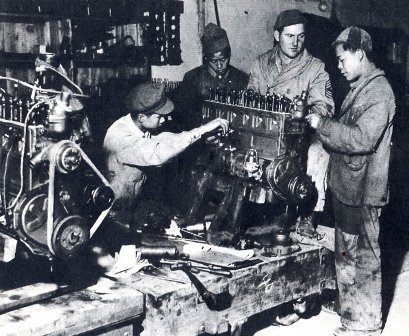

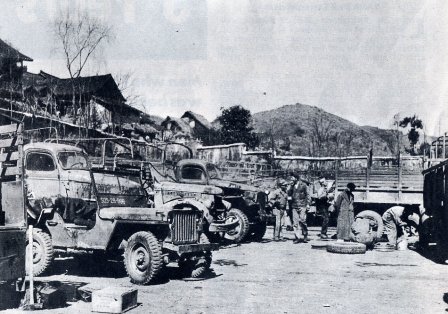

KUNMING, CHINA - For the American ground forces in China, the war is just about equal to the task of moving a mountain seven days a week. Here, supply is the big thing and, practically speaking "ground forces" means the Services of Supply who must move the mountains of equipment that the cargo planes bring in. There are other ground units here with just as important assignments, but they don't compare in size or scope with SOS. SOS's expansion has made Kunming like one of those old-time double-dip ice cream cones. It is a military city slapped on top of an Ancient oriental one - a combination that the war brought on and one that is working out with surprising success. China gives hostels to troops here through the War Area Service Command, an all-Chinese organization. But from there on SOS goes into operation. It brings in the water, the lights, the power; furnishes trucks; handles the loads; delivers the goods; brings the mail; repairs the vehicles; stores the supplies; fixes the weapons; maintains signal communications; tends to the sick, and furnishes the MPs to do the police work. America's part in this Far Eastern struggle does not stop with the dumping off of supplies at this end of the Hump. From here it moves to the fronts by land, rail and water. That operation involves a far greater amount of work than can be seen on the surface. A bearing in a truck hauling supplies may burn out. The tough part here is that you can't simply replace the bearing with a new one. A new part must be built from scratch. That's what goes on in nearly every phase of SOS work and to that difficulty is added a scarcity of tools and material. Half-way around the world from the original plant, there is another production line here tagged by the GIs, "The Little Willow Run." On one end of the line starts the rusty skeleton of a motor that might not have turned a piston in years. It'll come out of the other end full of life, ready to pull a truck over the mountainous route over which supplies travel. Chinese work right beside the GIs on this line, learning mechanics as they go. The Chinese, says Cpl. Mike Cascio of Brooklyn, are learning their jobs quickly, but there is still the difficulty of finding enough Chinese who can be

Another hitch encountered by the GI teachers is that the Chinese mechanic is too much of a specialist. If he's taught to wind armatures, he can't be taught to do anything else without forgetting what he had already learned. He remains strictly an armature winder. The shortage of good mechanics leaves a dire need for men versatile with tools. Little Willow Run is not a plant that could be compared in size with anything Detroit boasts. It's more like a neighborhood machine shop, turning out an unbelievable amount of work. If there's any Army vehicle here that has undergone repair, more than likely it has been doctored at Little Willow Run. It's the only thing like it in China. It has its own blacksmith shop run by GI-trained Chinese. It pours and "spins" its own bearings, a job usually confined to special factories for that type of work. It makes truck springs. They break on these China roads about as fast as popping corn. The plant rebuilds batteries that have once been given up for junk. Gasoline on this side of the Hump is precious, so trucks must be content to run on a mixture of one-quarter gasoline and three-quarters locally manufactured alcohol. The fuel works a burden on the motors and the men who are depended on to fix them. IN THE EARLY stages of China supply, planes were carrying few dismantled trucks yet they were sorely needed to move supplies up to the front. SOS had to purchase what it could in Kunming and surrounding cities. It bought whatever looked like it would go with a little fixing. The remains of some of these purchases can still be seen in the motor "graveyard" at the ordnance shops. They were repaired, used to the utmost and then fixed again until they virtually fell apart intro a heap of nuts and bolts. They're still using the nuts and bolts, incidentally. One of the GIs stuck out a greasy hand and said, "See that over there." He pointed out a pile of metal that at close look, bore the marks of once having been a Lincoln Zephyr. The Army bought it here and paid $12,000 in cold, shivering American cabbage for it. It had been used for all it was worth like all the others in the Little Willow Run graveyard. These scraps sooner or later will become parts of perfectly running vehicles. Though the Americans came here with a knowledge of mechanics, they came without sufficient tools. This is where the Chinese have something on them. The Chinese workman has been accustomed for long years to work with the crudest of implements. Once in a while he'll come up with a "hey, mac, look it here" and display a tool he's produced with sweat and a hammer. Fifty dollars American dough, has been paid for one machinist's file. The line at Little Willow Run - officially it's called the Unit Reconditioning Plant - runs on a small narrow gauge railroad borrowed from the Chinese. It winds and twists through several processes, but if straightened out would hardly stretch for more than a good city block. It's the only hospital in China for anything that runs on the ground by gasoline motors. Besides this, a body-assembly line is putting together the knocked-down trucks ATC hauls in by air. Most of them in the yard are noticeably old. Bodies for these trucks are made by the Chinese in a Kunming factory that can turn out only 10 a day, a bottleneck for the faster assembly line. The stock room it takes to maintain this miniature factory is loaded with available types of parts worth 10 million dollars. It works at top speed, turning out its contents to the bare walls every 45 days, then restocking again. About 15 GIs work six and a half days a week in the stock and records office to keep tabs on what goes where. Waste cannot be afforded in China. Consequently, the Army often gets more for an empty tin can than the can and its contents would cost in the States. Salvage operations of SOS, which have grown into a seven and a half million dollar (Chinese currency) total, reflects fantastic phases of doing business in China. SOS operates a glorified junkyard in an ancient Chinese cemetery. Ordinarily the job would be a drab matter, but it is made interesting by the development of markets and uses for cast-off tin cans, blown-out tires, worn shoes, bomb crates, aluminum from salvaged planes and some of the unusable auto bodies. Companies save and gather the stuff. Ten GIs, 25 native tailors, 12 shoemakers and nine yard men work at processing the junk.

Tin cans are a story in themselves. The junkyard gets $60 Chinese now and has received $180 for a single No.10 can - about a two-quart size. Buyers fight to get them. At the "open market rate" of currency exchange, which may vary from 300 to 400 Chinese dollars and more, the empty tin can brings about as much as it would filled with jam, fruit juice or almost any commodity back in the States. The cans are made into tea pots, pans, office supplies and lamps. Auto tires are much the same story. A well-used, blown-out tire of the regular size will sell for about $60 Chinese. Mended, they make tires for two-wheeled horse carts. The yard has handle more than 10 tons of scrap aluminum, a lot of it from Jap planes knocked down in the area. Arrangements are made with a local fabricator to turn out the metal into plates and pans for the mess halls. In the end, the cost will not be much more than the cost of native crockery which is always slipping out of the KP's hands. Some furniture can also be made from the salvaged aluminum. In the same way, much of the iron and steel scrap is converted into bolts, nuts and nails. Clothing and shoes are a different deal. Clothing is repaired for reissue - some as Class B, for ordinary troops' usage; and a lot of Class X, which is handed out to mechanics and truck drivers. Tailors are Chinese women who carry their babies to work with them in the Army's warehouse sewing rooms. Shoe repair is done for the GIs just like the corner repair shop back home. Old and irreparable tires are used to make soles and heels. Those so bad they can't even be used in this way are heaped into a pile and sold for good prices. THE "HUMP-BACKED" boys who are battered around day in and day out in the air by the rough Himalaya weather have conceded there is a tougher job than theirs over here when they see what the GI drivers in the truck companies put up with. Some are all in favor of seeing the drivers collect flying pay or similar extra compensation for their daily stints. "Flying pay" would be more appropriate than any other term because the truckers on the northern run hit altitudes of 15,000 feet where they also meet the airman's bugaboo of ice and fog. The dangers of these eastern and northern routes come by the hundreds and accidents are frequent (they knock on wood plenty around here), but deaths and injuries are low. The most remarkable incident recorded by one of the SOS truck companies happened to Cpl. Daniel B. Quick of Laurin, N.C. Quick was up about 12,000 feet, driving the middle vehicle in a three-truck convoy that was the tail-end of a larger convoy pushing north. He touched his brakes lightly as he approached a curve. They locked tight. The truck skidded into an icy spot on the curve, then spun off the edge of the cliff. "I remember distinctly making three complete somersaults on the way down," says Quick, "but it was all so fast I didn't realize what happened to me." What had happened was that Quick's truck plunged 500 feet to the next level of the mountain. The back end of the truck stuck in the mud and the vehicle settled slowly on its front wheels. Quick stepped out of the cab, adjusting his rimless glasses. They had not even been knocked off his head. "To save face, or what the hell you call it," Quick says, "I climbed up the side of the mountain as fast as I could and got into the next truck before I had time to lose my nerve. I was alright until that night when I got to thinking about it and then I went all to pieces." He was taken off the run for a while to give him time to forget the experience, but now he's back driving again. T-4 James Makowski, ace convoy mechanic of Jamaica, N.Y., who has been over most of China's roads in 20 months of service here, told of another accident that happened to one of the Chinese drivers. It was another case of a truck

The areas of these truck companies are much like the field of a fighter or bomber squadron. Drivers eagerly await the return of convoys. When they hear them in the distance, they poke their heads out of tents and the more anxious ones run up the road to get first word of the convoy's experiences. They're a rough-looking bunch when they come in with dust and grease of several days ground into their faces. Usually weather conditions are the first thing they talk about. Drivers about to go out learn what they can expect from those who have just returned. Fog in the high altitudes is the biggest evil. It gets so bad at times that the only way these teamsters can sneak a convoy through is by driving with the cab door open. That way they can watch the rocks on the side of the road to see where they're going. In some regions, fog, sleet, rain and snow are only part of the dangers. Convoys must be on the lookout for bandits armed with everything from old rifles to up-to-date tommy guns. Some are Chinese deserters and others are professional bandits who have been prowling through the hills for years. It's a rugged life for drivers when they're on the road. They are plenty familiar with the contents of a K-ration box, but sometimes they are able to supplement that in a village with a Chinese dinner. But there are few of these places and still fewer that have been okayed by medical officers. At times they get close to the Siberian border, always a good spot to them because of the strong Russian coffee. Occasionally they eat and sleep in old missions still to be found in China. Sympathetic families sometimes take them in for a night's lodging. A greater part of the time, their trucks are their homes until they reach their destination, and return to camp. Whatever medical care is needed while on the move is supplied by the busy "Country Doctor," 32-year-old Capt. Robert Gneuhse of Cleveland, Ohio. When an ambulance is not needed, Capt. Gneuhse bounds over the convoy route in a jeep and, like the typical country doctor, he travels the road at all hours of the day and night, maybe to pull a tooth, set a broken bone, or bring in a driver with a high fever. THE FIRST TWO men to lead a convoy to the eastern points were Sgt. Robert Parke of Staten Island, N.Y., and Sgt. William Gleason of Syracuse, N.Y. They agree on a comparison that driving over some of its course is like trying to put a car across a kitchen shelf. Some of the road is actually a shelf hewn into the rocky side of a mountain. Nothing is on the outer edge but space that goes down hundreds and sometimes thousands of feet. They have driven over this treacherous course for several hours at a stretch to avoid putting through a night of penetrating cold. Cpl. Edward Braber of Chicago and Pvt. Jimmie Morris of Atlanta, Ga., had an experience with the sub-zero weather they don't want to live through again. Their truck broke down and unnoticed immediately by the front of the convoy, they were left behind. With a Chinese apprentice driver, they were forced to endure 24 hours in the truck's cab which had turned into a solid block of ice. "We only had a couple of blankets with us that time so we tried to keep warm by bunching together in the cab," they related. "Jimmie and I managed to get a little sleep," said Braber, "but the Chinese driver was in a bad way. His clothes were pretty light so we put him between us and tried to keep him from freezing that way. The next morning we thought the Chinese was a goner because he turned black all over." They didn't realize it, but their rescuers said that their own faces were also turning black. The convoy noticed they were missing when they pulled into the next way station and one of the trucks was sent back for them. S/Sgt. Clarence Swanson of Atlanta had a similar experience that lasted three days and nights. He was stranded at a less frigid altitude and was able to keep fairly comfortable by burning an extra supply of fuel alcohol. "Those damned bandits were the thing that had me worried," Swanson says, "because they'll jump a GI especially when he's alone." The cargo gets delivered with a determination that has brought one of the companies the Presidential Unit Citation. About half of these men never handled a truck before their entry into the Army. Cpl. James Lucido, a driver from Detroit, is one of those. He's been handling the big GMCs and Chevvies for more than nine months and he's gotten through every day without an accident. He was a service man on adding machines before the Army made him a truck driver.

|

|

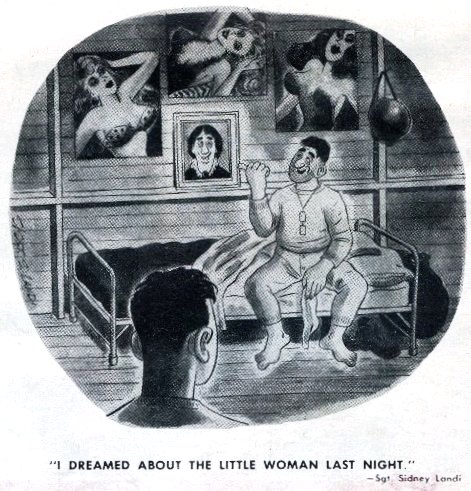

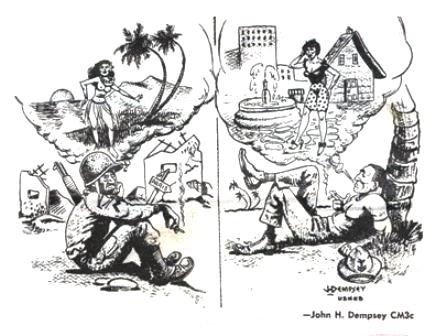

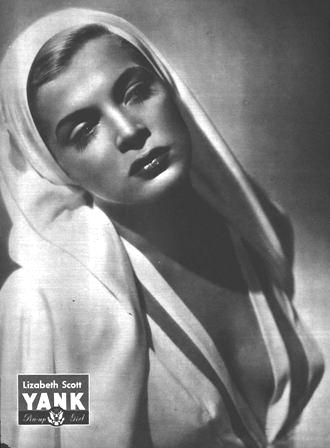

Rice Paddy Midway

HEADQUARTERS, WEST CHINA RAIDERS - One more American institution moved to the Far East recently, as west China GIs by the hundred rallied to a state fair playing a successful two-day stand on foreign soil. Held along a "rice paddy midway," the carnival lacked piled-up pumpkins and stacks of corn shucks, but the spinning wheels of the concessions were reminders of home, despite prizes which included Foochow lacquer and Chinese toothpaste. Point-shy American soldiers took part in the West China League's all-star ball game, tossed pennies into floating saucers, and loosened-up rusty pitching arms in the bottle arcade. These and other concessions were sprawled under a big-top, Coney Island fashion, and the winners were allowed to select their own prizes from heavily-laden shelves. Among the uniformed barkers was T/Sgt. Carl A. Antonucci of Steubenville, Ohio, who ran a successful bingo parlor, and T/Sgt. Robert W. Cleveland of Tampa, Fla., concessionaire of the archery range, who offered a "fin" for every two out of three bull's eyes. Other carnival-wise soldiers presided over wheels of chance, ring the peg and hit the bottle games, and the penny arcade. One keystone of the fair was the "Pin-Up Paradise," where 1,500 soldiers voted for Sweetheart of the West China Raiders. From a gallery of 75 Hollywood beauties, Hazel Brooks walked off with the winning colors, followed by June Allyson and Jinx Falkenburg in the place and show positions. Unlike most state fairs there was no food exhibition, but Sgts. John Anderson and Alfred V. Casinell fed the crowd on cheese and hamburgers, tuna fish and chicken sandwiches., apple and peach pastries, ice cream, fruit juices and Coke. Entertainment came in the form of a radio broadcast featuring the tunes of the "Esquires," a newly-formed orchestra under the direction of Sgt. Dave Salustri of Akron, N.Y. As a special attraction, the "Skyline Caravan" came from Calcutta to present a novelty musical-burlesque starring GIs at one time well-known in the stateside entertainment world.

|

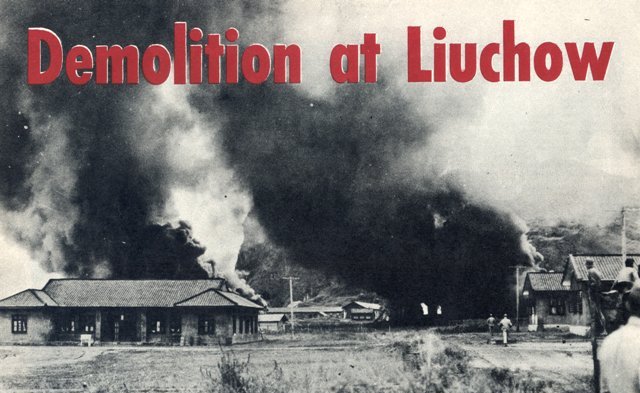

For it was this heavily-bearded former base commander at Hengyang who had presided over the evacuation and demolition of his own base, Lingling, Ehr Tong and the bomber field at Kweilin, all former U.S. bases laying in the path of the big Jap campaign to link Manchuria with Indo-China. Liuchow was next and the onrushing Jap armies were converging on the city from the north and from the south. Wilson's arrival was the tip off to a city which, from outward appearances, belied any such foreboding. An atmosphere of deceptive calm lay over this ancient city, once famed as a manufacturing center for coffins and known in other days as the southern terminus of the "Opium Road." In the Loh Chun hotel in the city, several miles from the airfield, GIs of the Air Service Command with business in town were still being served excellent meals by suave Chinese mess boys and sleeping in well-appointed rooms. Leaden, rainy skies brooded non-operationally low, sending mists swirling around hill tops and reducing to a faint hum the normal roaring of planes coming and going from the air base. For the past six weeks, since the destruction of most of the Kweilin fields, the Liuchow base had been the headquarters and right arm for intensive operations against Japanese troops and shipping by Brig. Gen. Clinton D. (Casey) Vincent's East China Wing fighters and bombers. A few MPs continued to patrol their beats, although the city had been out of bounds for weeks to soldiers not on official business. There were still a goodly number of Chinese civilians in the city, but it had ceased to be the refugee capital of south China. The great horde of refugees had swung westward and had bogged down at Ching Cheng Chiang and Ishan for lack of transportation beyond these points. Liuchow had been restored to a semblance of its old provincial calm. To make completely plausible the city's air of tranquility, a USO-Hollywood Victory Committee show, headed by Pat O'Brien and Jinx Falkenburg arrived to give a performance for the GIs at the air base. The came in time to be given a hot, pre-performance reception by Jap bombers that took the night before the scheduled show to paste the air base for the 16th time in 48 days. Four days later the tactical situation had reached such grave proportions that hope of keeping even a small part of the Fourteenth Air Force's strength in that area was abandoned and everything was ordered flown elsewhere. To 1st Lt. Willard G. Freeman of Concord, Mass., base commander, went the order from Gen. Vincent to carry out the base demolition plan. While Freeman and his crew were burning buildings and blowing up bomb slots, transports were being landed and flown out, with P-40s tailing them all the way. By early evening the burning of the buildings had been virtually completed, with headquarters, the hostels, and the mess hall now enveloped in a mass of flame. AT 0241 HOURS on November 8, two officers and three enlisted men of the Engineers sat in jeeps at the south end of a dispersal taxiway while ten to fifteen thousand Japanese troops converged on the field. Beside the two vehicles was an uncovered hole in which was buried a fused 1000-pound bomb - one of the 81 such bombs buried throughout the field to blow it to hell and make it useless to the enemy when he arrived.

The rapidly shifting positions and movements of the enemy were then unknown, but final intelligence reports received 12 hours earlier located Jap cavalry forces 12 miles to the north of the field, 30 miles to the east and 50 miles to the southwest. The only escape route open for the demolition crew when they finished their work was the Liuchow-Nanning road down which they would have to travel 38 miles toward the oncoming Japs before they would reach Tatang where they could turn and head northwest toward safety. Whether of not the enemy had taken Tatang and pushed nearer to Liuchow in the past 12 hours was anybody's guess. Burning of the installations had been going on since early the previous afternoon. By 0230 hours the following day the destruction of the base had been carried out except for the blowing up of the main runway, fighter strip, taxiways and dispersal and revetment areas. Lt. Freeman and all but five of the original demolition crew of 23 men then left the base in motor vehicles to proceed to a rendezvous point a few miles southwest of Liuchow where they would wait for the Engineers to join them after the field's demolition. It was this group of five Engineers who waited in the two jeeps beside the 1000-pound bomb. In one vehicle was Capt. James T. Sabel of Cadiz, Ky., who was in charge of the five-man detail and who was making his debut as a demolition expert. With him were 1st Lt. Emil Heineke of Lovelock, Nev.; Sgt. Anthony T. Turato of New York City; Sgt. John T. Galloway of Corona, N.Y., and Cpl. Rudolph P. Nagel of Cheyenne, Wyo. Their job was to drive down the field and set the buried bombs off by pulling the hand fuse lighters. These bombs were buried nose down and were fused with blocks of TNT to which were attached seven-minute lengths of time fuse. A cold, driving rain was falling as it had been doing intermittently for the past five days. As the detail stopped before the first bomb in line each man felt a dread that the steady downpour would cause malfunctioning of the time fuses and lighters. If so the whole job would have to be done over, wiring and fusing and then setting the bombs off a few at a time before the fuses could get wet. This meant hours more of work with the possibility that the enemy would reach the field before demolition could be completed. Capt. Sabel pulled the hand lighter on the first bomb. Wet, it came off without igniting the fuse. He put on another lighter and this time the fuse ignited with a gentle hissing sound. He leaped back into the jeep driven by Lt. Heineke and raced down the taxiway, followed by the second jeep with Turato, Galloway and Nagel. This second jeep followed for use in an emergency in case of mechanical failure of the lead vehicle. The next four lighters lit their fuses when pulled, but the sixth failed to work and had to be replaced. The speed of operations was appreciably slower than called for in the demolition plan. The rain caused poor visibility and made it difficult to see the bomb holes in the jeeps' headlights. The next three lighters functioned and the first bombing run was over. The men drove to a safe distance from the last bomb and waited for the already overdue sound of explosions which should have started about half-way down the taxiway. "They won't work!" Capt. Sabel said. "I've been afraid of this all evening. Too much rain!" Then, 18 minutes after pulling the first lighter, four blasts were heard in rapid succession and the men mentally chalked off that taxiway. THE CREW then drove to the end of the fighter strip, which housed eleven 1000-pound bombs for its destruction. The hand fuse lighters on the second and sixth bombs were no good and had to be changed. On the eighth bomb, Sabel pulled the lighter, found it defective and put on two more in succession. Neither ignited the fuse. He then tried to light it with matches which were quickly put out by the rain. As he struggled with the matches, the first bomb thundered at the opposite end of the strip. "Boy, what a beautiful sound!" exclaimed Cpl. Nagel. Sabel nodded and continued with his work, finally lighting the fuse. Sixteen minutes from the time the first fuse had been lit, the run had been completed and a satisfying roar hit the crew's ears as their own strip was blown sky-high behind them. The men felt better now. The bombs had gone off on schedule and the threat of Japs arriving before they had finished their job was erased from their thoughts. They laughed and joked as they waited for the last bomb to go off on the strip. Even Capt. Sabel's stern face relaxed in a grin. They had, to all appearances forgotten the little matter of their own getaway when the whole job was done. When the last bomb went off they drove to the north end of the strip to inspect the damage. There they found a crater about 15 feet deep and 35 feet in diameter. The whole end of the strip was deeply littered with rocks and earth. The preliminaries were over now. Next came the main event, a synchronized double-feature action in which the main runway and the parallel taxiway would be blown up together. The runs were split up this time. Heineke, Galloway and Nagel pulling the lighters on the main runway and Sabel and Turato on the taxiway. The simultaneous runs were necessary because of the closeness of the runway and the taxiway. Blowing up either alone would have littered the other so much that a jeep could not have traversed it to make a run. Heineke and his men had 30 bombs to locate and set off. Sabel and Turato only 10. It was therefore necessary that

On the main runway the 30 bombs were spaced in three rows of 10 bombs each. Each man in Heineke's jeep took a row. Each had a few seconds to locate his bomb in the rainy darkness only partially dispelled by the jeep's headlights. Then, Heineke would yell: "Ready?" As each man found his bomb he would call back: "Okay." Then Heineke would command: "Pull!" At most of the stops one or more of the wet lighters had to be replaced. Half-way down the main runway, Cpl. Nagel was putting another lighter on his fuse, while the fuses of 14,000 pounds of bombs were burning behind the waiting jeep. As he worked, a roar from the end of the runway announced the explosion of the first bomb. He finished his job, ran back to the jeep and it headed for the sixth stop. On the way, a second explosion occurred. While the crew was working on the seventh row of bombs there was another explosion; then four more followed, like a string of super-giant firecrackers going off. :See how fast you can run now, Pop," said Sgt. Galloway to the 38-year-old Nagel at the eighth stop. Here, Galloway's lighter needed changing as he worked four more explosions sounded in quick succession. They then continued to go off at close intervals while the crews finished the runway and taxiway and headed for the east dispersal taxiway. Both crews worked this one, leap-frogging from stop to stop. At the half-way mark the bombs behind them started going off. It was 0418 hours now, two hours and 17 minutes after pulling the lighter on the first bomb. Liuchow air base would not be much good to the Japs for some time to come. THE NEXT problem was getting away. The jeeps sped from the razed, blasted base and headed down the Liuchow-Nanning highway to join the rest of the demolition crew waiting for them a few miles away. To their left they could see dark geysers of earth shooting high into the air as the east dispersal taxiway blew up. A few big fires were still burning on the field, but most had burned out. A short distance down the road the five-man detail joined forces with Lt. Freeman and his crew. The convoy then raced toward Tatang - hopefully. After two hours of driving Tatang was reached. An artillery officer whose combat team was on duty there with Chinese troops met them. "Don't take more than 10 minutes to get out of town," he told them. They didn't. In the center of town, they turned northwest and headed for a base 700 miles away.

|

As the best port along 800 miles of the Bay of Bengal coast from Calcutta to Bassein and Rangoon, Akyab was needed by the British to supply their stepped-up land offensive in Central Burma. Twice before they had tried to grab it from the Japs - one year and two years ago - but each time they had too few men and landing craft and too little close air and naval support, so they were forced back. Then a few weeks ago their infantry finally began a drive down the long-dormant Arakan Coast that carried them to Foul Point, five miles across the mouth of the Mayu River from Akyab Island. The stage was set for another try. This time, by begging a few dozen landing craft from the Sicily and Anzio beachheads and by building others in India, the British massed the first large-scale amphibian force they have ever assembled in Far Eastern waters. Ten squadrons of fighters and bombers were to start the D-Day off by giving the six-by-ten-mile island a good pasting. Cruisers and destroyers were to move in for a naval bombardment. More than 50 guns were dug in on Foul Point to shell the island's coast during the landing. Commandos were to hit the beach first, secure it, and then the infantry and tanks would follow up by driving along the main road into the city itself. A few hours before the invasion, as the armada of fighting ships and landing craft plodded through a heavy ground swell down the Arakan coast in the morning sun, the Commandos who were to be in the first wave were making up their packs and giving a final cleaning to their weapons when an announcement came over the ship's loudspeaker: "Well, chaps, it looks like this will be nothing more than a ruddy club run. We have just received a report that the Jap has left Akyab Island. The aerial and naval and artillery bombardments have been called off, but the rest of the operation will go on as planned. Watch your step just the same - there are reported to be mines and booby traps all over the place and there might be a few snipers." The Commandos in their green berets and jungle suits groaned with disappointment. Some of them had been in raids across the Channel, others had run ashore in Tunisia, many had been in the Madagascar invasion, one or two had survived Dieppe and their engineers had crawled onto the Normandy beaches on D-Day. The effect of the announcement was sudden; they had been tense and silent, but now they relaxed into shrugging boredom. "Nothing now," muttered a lance corporal, "but a blahsted exercise."

AT 1030 HOURS the little assault craft came alongside the Australian destroyer. The Commandos put on their packs and climbed down into the bobbing boats. I climbed down with them, into the boat that would be the second one to hit the beach. Two miles away was a low strip of land, dotted with trees and dunes and looking peaceful and empty in the morning sun. After circling the destroyer awhile, waiting for the other LCAs to take on men from the other destroyers, the craft got the go-sign, fanned out and sped toward the show as everyone crouched low. In a few moments our LCA crunched on the sand, the ramp grated open and we stood up and raced through ankle-deep water onto a broad beach. Before us was a three-stranded barbed wire fence. We raced up to it, squirmed through and made for the brush-covered dunes. Now we could see the slits of pillboxes built into the dunes so skillfully they could only be spotted from a few feet away. The Commandos circled each one with ready rifles and peered in. Each was empty. There were trenches all over the place, but these too were empty and in a crumbling state that showed they hadn't been occupied for several weeks. Moving at a half-trot, the Commandos headed inland, hastily inspecting every thicket and every emplacement. Not a shot had been fired. The silence seemed mocking. Going back to the beach to watch the progress of the landing, I watched LCTs slide in to disgorge jeeps, tanks and trucks. Ammunition and supplies were being carried up the beach by long lines of soldiers. Two Hurricane fighters roared low overhead with silent guns, and a tiny liaison plane circled lazily above the scene. The tanks were General Shermans of a cavalry squadron that is directly descended from the Bengal Lancers. Most of the drivers and gunners were Sikhs with beards and turbans and most of the officers were British.

Soon the Shermans were racing down the road past single-file columns of Commandos and across broad fields of dry rice paddy land. Occasionally they came to rows of tank traps that had been built months before and were overgrown with grass. But there were no mines in the road and none of the little bridges along the road had been blown by the Japs. By dusk the tank squadron was bivouacked halfway across the island. The only local inhabitant we saw all day said the Japs had left the island in boats three days before, wearing civilian clothes. Still expecting some sort of Jap ruse, the Commandos and tank men dug foxholes and put out perimeters for the night. NEXT MORNING, after a breakfast of thin, milky Sikh-style tea, hard biscuits and jam, the tanks got underway again. By that time, the infantry had begun passing through and was walking the last few miles toward the city. There were tough little Ghurkas carrying their deadly kukri knives, and big Britishers in floppy felt hats. Within half an hour of bouncing in and out of tank traps and ripping through barbed wire fences, the tanks came to the first of two temporary airstrips. It, like the tank traps and pillboxes, was overgrown with grass. It was lined with

"This fellow says there's a sick Jap who's been left behind," the lieutenant told the CO. "He's at the old commissioner's bungalow in the city." The CO had just sent a jeep into the city on reconnaissance, but when he couldn't contact it on his radio he turned to another officer and told him to take a jeep and try to find the sick Jap. Six others, including the informant piled into the jeep and I sat on the hood as it moved away across the fields, hoping to get pictures of the only Jap in Akyab. The jeep got on a two-lane macadam highway that once used to be the main supply route from the docks of the seaport to places north of the island in Burma, ferrying a couple of rivers en route. As the jeep raced along the road, little bunches of people came out of hiding and lined the way, not cheering but saluting, which is an Oriental gesture of greeting. Their poker faces seemed to say, "It's about time." When a few bowed low at the waist, the British officer said, "That's the Japanese influence." When the jeep arrived at the bungalow, the Jap was gone. The informant showed us where he had been lying the day before.

"There were only a handful of Japanese here there the last few weeks," the person said through a Sikh interpreter. "The last thing they did was dig holes in the airport runway, plant mines in the holes and blow them up." The airport was near the bungalow, so we walked out on the runway, past the bomb-blasted hanger once used by the British Overseas Airways on the Indian-Australia run. There were stacks of boxes about the size of coffins like those that had been placed in the holes, filled with explosives and blown up. The charges couldn't have been very powerful, for each demolition hadn't made a hole any larger than that made by a 220-pound bomb. We piled into the jeep again and rode into the middle of the city. There wasn't a soul in town. Nearly every street was overgrown with grass. Akyab had long been one of the main targets for RAF and American bombers, and the raids had deroofed and wrecked every building. A CITY OF 30,000 before the war, Akyab still showed some signs of its once prosperous days. There were two or three imposing bank buildings, huge warehouses and department stores, factories, a jail with high walls, a block-long

The British flag was flying on the jetty. In the water taking a swim were two tank officers who had preceded us into town in the first reconnaissance jeep. They said a naval officer had come ashore from a destroyer the day before to put the flag up. Not only had the entire operation been as quiet as Carolina maneuvers, but the Japs had added an ironic touch by policing up the area as thoroughly as a Stateside garrison before a Saturday morning inspection. In an hour of wandering through buildings and peering into pillboxes, none of us found a single Jap flag, rifle, helmet, saber or bullet. The Japs had combed the place clean. The only weapons I could find were three rusty old 75-mm British cannon lying in the grass beside a road that hadn't been used for a year because of a bomb crater that blocked it. "These cannon," the tank officer said, "have been in Akyab since the 1800s." When we left the silent ghost city about noon, the first infantry troops were trudging in, their hobnail boots clattering hollowly in the empty streets.

|

Claire Lee Chennault came to China eight years ago to lay the plans for what eventually became the U.S. 14th Air

Force. Now he has gone home and for the first time in his 55 years he doesn't know what to do next.

Claire Lee Chennault came to China eight years ago to lay the plans for what eventually became the U.S. 14th Air

Force. Now he has gone home and for the first time in his 55 years he doesn't know what to do next.

Agent No. 254, having a good knowledge of military aviation, came to China eight years ago to help the Chinese plan ways and means of beating Japs. Like most Americans at that time, he was a civilian. The agent advised, planned and suggested and then left China the first time to return to his country flushed and enthused with a proposition for China's aid. He proposed to come back to China with American airplanes and the men to fly them. About four years after his first invitation from Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, he did come back and in the middle of 1941 the United States had sent him a hundred P-40s. The U.S. Army had also sent him a uniform and a pair of silver chickens. Agent 254 became Col. C.L. Chennault and as such headed an air force that fought a war using rifles and pistols against Jap aircraft. The daredevil antics of his Flying Tigers, men of the American Volunteer Group, became a legend that grew up with the kids of that decade. Chennault fathered a family of young sympathetic pilots which grew from the AVG to the China Air Task Force and finally to the U.S. 14th Air Force. Today there are no Japs in the sky over China. It has been seven months since Japan took a last poke at this city of Kunming. Now the sons are fully grown and they've said good-bye for the last tome to the "Old Man" who had fostered them through eight years of pinch-penny existence. Chennault left his men as a Major General. He has asked the Army to retire him from active duty and to return him to his home in Water Proof, La. He went back to Water Proof as quietly as the departure for China of Agent 254. There were no noisy celebrations for this returning general. YANK interviewed him before he left China and it was plain as day that here was an aging man, who had absolutely nothing planned for the future. This was one of the few times in 55 years that Claire Lee Chennault didn't know what he was going to do next. The official request for retirement said "for reasons of health." It is hard for his men to see what could be physically wrong with a man who still holds the best softball pitching record in the 14th Air Force. Last season pitcher Chennault chalked up seven wins against only three losses on the mound. He has a batting average of well over .300 and his performance as a base runner, they say, never would indicate that he was always the oldest man in the game. When he announced his request for retirement in an earlier press conference, someone asked Gen. Chennault about his health. The General asked the reporter to repeat the question. The reporter asked it again. Still the General didn't hear. He cupped his ear and asked for the question again. Louder, the reporter asked: "Specifically, General, what is wrong with your health?" "Well, you see," the General replied, "I'm still deaf as hell." DEAFNESS CAME from the many hours Chennault spent as a youthful pilot of a pusher-type airplane where the motor is very close to the pilot's head. Chennault's men have been shouting at him for a long time and they can't see now why suddenly this should force him into retirement. The answers they would like to hear have gone with a saddened man who tried to smile when he went away. The "Old Man" has done a lot with airplanes since he saw his first one 34 years ago. That was when he was a schoolboy at Louisiana State Normal. He got close enough to touch a pusher-type airplane one day at a state fair exposition and vowed "right then and there that I was going to fly." I asked the General if he could remember how he felt the very first time he climbed behind the controls of an airplane to take it up himself. "I do remember that I didn't have the slightest bit of apprehension," the General replied, "and when I got the thing off the ground, I had no sensation whatsoever of flying. It was like sitting in a chair at home and, as a matter of fact, I have always felt at home in an airplane ever since." And ever since, he's either been in airplanes or close around them, never losing his first enthusiasm to fly. Some of the old ground crew men of the 14th tell of his frequent visits to the line and how one day he became so engrossed in what a mechanic was doing that it resulted in another two-star general getting a bit sore for having to hold up a luncheon date with Gen. Chennault until the 14th CG helped the mechanic dope out the engine problem. His down-to-earth attitude and democratic practices are the things men say they will miss most. They seldom saw their commanding general dressed in a starchy spit and polish outfit that comes with rank. The General's favorite outer garb is an old battered flight jacket with a small leather tab over the left breast simply lettered C. L. Chennault, like every fighter pilot wears. He once put the clamps on an officers' club and refused to allow one to be erected before there was such a club for the enlisted men. In the 14th there has been no such thing as KP or guard duty as a regular detail. The General contended that he needed every man on the job of flying and keeping in condition every bomber and fighter. By skillful persuasion and influence he was able to enlist the Chinese for such duties as guard and KP. He was never a stickler for his men's appearance although being a soldier to the core (he used to stand at attention in his office when he heard the retreat bugle from a nearby Chinese compound). He felt his men were too busy to give much attention to their clothes and most of the time they either had to work in mud or when it was dry, in desert dust-storms. LAST OCTOBER Gen. C.L. Chennault (he'd rather have it C.L. because he thinks Claire is a girl's name and he doesn't like Lee) told a YANK reporter that he thought Japan's collapse would come within six months after Germany's surrender but in this interview the farthest he would go on a prophecy was to say that "there is always a possibility that Japan will surrender, but the chances are about 50-50 they will not. But with a constant need for economy in men and material, Chennault's air force has been doing its damndest in the past three years to make that first prophecy come true. In three years of the 14th's operations, Japanese air strength over China has been whittled to a splinter. Bombers have destroyed over two million tons of Jap shipping. Japanese communications to China's coast, the southwest holdings and to Formosa have been snapped. The 14th has destroyed more than 1,000 bridges, 2,000 trucks and armored cars. By direct aircraft fire more than 60,000 Japanese soldiers have been killed. In blasting the Japs out of China's sky, Gen. Chennault has been credited with many "circus plays" which have placed him among the most glamorized and legendary air generals of this war. Actually, every one of these "circus plays" have been shrewd and deliberately-planned offensives and their successes were almost a sure thing before the planes took off the runway. With the dribble of supplies coming over the Hump in the early stages here, every drop of gas and every ounce of bomb had to count. With such shortages on this side of the Hump, all the large operations against the Japs from China bases had to be an attempt to kill three birds with one stone. When 16 Mustangs from the 14th cut up 73 convoy ships in the South China Sea, their attack was loosed at a time when the Japs were certain that our fighters and bombers did not have the range for such strikes. Consequently Jap warning nets in that area were allowed to go to pot. The Japs were caught and riddled without warning. Similarly, Shanghai had been bombed, hit so hard and at such closely-calculated time to make that city useless to the Japs as a springboard for any attack against American forces on Okinawa. Formosa was kept out of the play the same way. Testimony to the close economy the "Old Man" has used in beating off the Japs, is an eight-month record of B-24 operations. During that period there was one and five-tenths gallons of gas used for every ton of enemy shipping sunk. For every ton of bombs dropped by the 14th in that period, 956 tons of enemy merchant shipping went to the bottom. Gen. Chennault repeated an early statement in which he said: "I don't expect that we will ever get so that my operations in China will be decisive in this war. But the steady and increasing attrition we are inflicting on the Jap is considerable. If we can support the main fatal blows from the Pacific by containing a large Jap force in China, we figure we will have accomplished a great deal and have done our job." It looks like that part of the job is just about done. It has been a long tedious stretch since the days Agent 254 of Louisiana's Conservation Department came to China and organized his Flying Tigers, a time when he says the best bargain he ever made in his life was with the Chinese when he contracted to house each of his men with the War Area Service Command. "The Chinese agreed to put my men up for a dollar a day then," said the General, "then look what happened to the prices here since and the best part of it is that the dollar-a-day contract is still good." Looking down at his fingernails he was picking with a knife the "Old Man' said: "The greatest regret in my life is to leave my men. They've fought loyally and damned hard under the worst living conditions." In parting, on behalf of many GIs who have asked the question, I asked the General to make a comment about rumors that the 14th was going home in a body. He answered: "I never heard of and I know of no plan for the 14th Air Force going home right now."

|

|

September 1, 1945 edition.

|

|

|

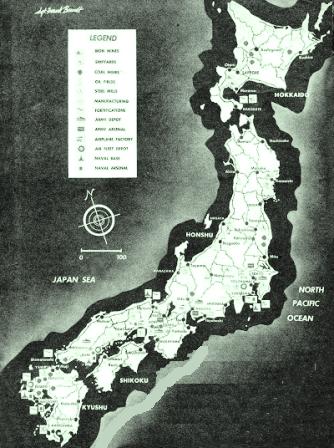

With B-29s now operating from China and new air bases available to U.S. Fortresses and Liberators in the western Pacific, these war production centers await relentless day and night bombing. |

YANK

THE ARMY WEEKLY

China-Burma-India Edition - Part Four

Copyright © 2005 Carl Warren Weidenburner

CBI EDITION INDEX

Visitors

Since March 31, 2005

| YANK, The Army Weekly, original publication issued weekly by Branch Office, Information & Education Division, War Department, East 42nd Street, New York 17, N.Y. Reproduction rights restricted as indicated on the editorial page. Entered as second class matter at the Post Office at New York, N.Y., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Subscription price $3.00 yearly. China-Burma-India Edition printed by G.B. DASS at the Eagle Lithographing Co. Ltd., Calcutta. |