|

1st Provisional Tank Group

China-Burma-India Theater of World War II

The joint Chinese-American 1st Provisional Tank Group (1st PTG) was as remarkable a unit as any raised in World War II.

The recipient of relatively little recognition even while fighting in the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations (CBI),

today the unit's obscurity is nearly complete.

Those who fought in the CBI Theater found its adverse geographical and climatic conditions a test in

themselves. There was thick, triple-canopy (80-100 feet tall) in most of the Burma-India region, which dropped often

to swift-flowing rivers. The western slopes of the mountains had decomposing vegetation 3-4 feet deep in the jungle

clearings, 6 foot tall Kunai grass clotted the sites. Winter brought chilling cold and heavy ground fogs.

Roads were poor to non-existent, consisting mainly of cart trails. An additional problem faced by all

personnel, military and civilian alike, was the constant threat by dangerous animals, which ranged from leeches to

poisonous snakes (with fatally potent venom). Tropical diseases, some with symptoms never before seen by "civilized"

physicians, attacked all with impunity.

In addition to the poor road system throughout CBI, the weather adversely affected mobility. There was

little combat during the Monsoon. Everything was impassable, even on foot. The vast majority of the combat in CBI could

be considered guerilla warfare; battalion-sized actions equaled divisions in other theaters. The geography and climate

had a major impact on troop movement, logistics, planning, and all general phases of military activities.

1st Provisional Tank Group |

The geography of the area in which the 1st PTG operated was dominated by mountains on three sides. The Himalayas were distant to the north, and the Patkai range runs southwest to meet the Himalayas with a height of 10,000 feet. On the east the Himalayas curve southeast into the Kumon range, also 10,000 feet high.

The 1st PTG was originally activated at Ramgarh, India on Oct. 1, 1943. It was a joint Nationalist Chinese and American unit with a unique rank structure and Table of Organization. The 1st Provisional Tank Group, commanded by U.S. Army Col. Rothwell H. Brown, was composed of six provisional tank battalions, all Chinese ("Provisional meant temporary unit identification - and subject to change). Unlike Stilwell, Brown had made friendships within the Chinese Army, dating back to his first posting from 1930-34. One was Chiang Kai-shek, and the other was Chao Chi Hua, who would go on to command the 1st Tank Battalion of the 1st PTG. Brown learned some Chinese dialects, albeit not as proficient as Stilwell.

As an advisor to the Chinese Army, Brown had some of the earliest U.S. exposure to Japanese Army tactics. Brown, originally an infantry officer, learned that the Japanese military success in China demonstrated that armored forces could have success in that area and were a limited necessity. Upon his return to the U.S., Brown began training in armor tactics. Brown's interest in armor led to leadership expertise that was recognized by many, including Stilwell. Stilwell called Brown to the CBI Theater with instructions to apply his leadership and knowledge to Chinese tankers and supporting infantry battalions.

The 1st and 2nd Tank Battalions (Provisional) were supplemented by a company-sized contingent of Americans, with an enlisted strength of 222 men and 9 officers. The 1st Battalion was commanded now by Lt. Col. Chao Chi Hwa beginning in March 1944. The 3rd through 6th Battalions (Provisional) were essentially Chinese training battalions, with American advisors. Total strength of Chinese personnel in the group (all six battalions) was over 1800 men. The 1st PTG had an integrated staff with a Chinese Vice Commander, Col. Chao Chen-yu, who worked closely with Col. Brown. All of the Chinese tank battalions had English speaking officers, trained and educated in the United States. The U.S. officers all had equivalent rank in the Chinese Army.

|

Additionally, the American contingent derived most of its personnel from a regular U.S. Army unit, the 527th Ordnance Company (Heavy Maintenance) (Tank). Brown wanted a unit like the 527th because of the tactical need and its unusual ability to all perform all maintenance in the field. Back in the U.S. the 527th had been raised from North Carolina state highway road crews, and trained with the III Armored Corps. During most of its tour in the CBI, the 527th Ordnance was commanded by Capt. Tom A. Miller, who was replaced on June 22, 1945 by Capt. John W. Hutchinson. The 527th had reached the CBI by a lengthy route via Oran, North Africa and Calcutta, India.

Among the first assignments by the 527th was an advance party of 44 personnel acting as advisors to the Chinese forces. Sgt. Joe Crawford was an original member of the 527th Ordnance. Trained an infantryman, he joined the 527th at Camp Rucker, Alabama in November 1942. Crawford recalled: "At Camp Polk the C.O. told us one day that 45 of us were being ordered to Karachi, India, to set up a base shop for the 527th, which was being transferred. Once the detachment arrived (less one man injured in a traffic accident) we began servicing approximately 145 M3A3's. The tanks had their machine guns, radios and periscopes in boxes on the backs of the hulls." The men also obtained almost 200 6x6 trucks, 50 jeeps, as well as several command cars and 3/4 ton weapons carriers.

In October 1943, they met Col. Rothwell Brown in Calcutta, where they learned that they were setting up a Tank Training School for the Chinese Army. The men were sitting in the shade of lumber stacks, and Brown told them to "Expect to stay for five years. The Chinese were all handpicked, but God only knows who handpicked them." It was unknown at the time if the Chinese would fight.

T/3 Lennie House recalled: "I was in the advance party led by M/Sgt. Carl Beck. At Ramgarh, I trained 18 Chinese soldiers, some as young as 14 years old, in everything from maintenance to tank driving. These soldiers had all been farmers or rural laborers, and had never seen a truck, let alone a tank. Their officers spoke English, and we did the best we could. They tried very hard to learn what we were teaching them. I got along real well with several of them, and gave them American names so I could remember them. We spent two months training them, and then were surprised that Stilwell directed us to lead them into combat. We never had a chance to train in armor tactics, until much later. I also had to drive a tank from Ledo across the Himalayas to the Hukawng Valley during the monsoons, to see if it could be done. It worked out, so Beck, myself, and two other men transported the rest of the tanks in January 1944. We had to switch trains twice because of different gauges, and then drove the tanks the rest of the way."

Not everyone assigned to the 1st PTG initially came from the 527th. T/3 Howard Bickel said "I received armor training at Fort Knox, but was working on the Ledo Road in 1944 driving a bulldozer. An officer and 1st Sgt. came over and said, 'All of you dozer drivers have just volunteered for a tank unit' because the officer and 1st Sgt. knew that we had armor training."

|

The 1st PTG fought much of the early part of the Northern Burma campaign with M3A3 light tanks, armed with 37mm guns. It was authorized 100-125 M3A3's at any given time. M/Sgt. Carl Beck, who led the 44-man training detachment, didn't like the M-3's. He said, "Japanese 47mm AT guns went right through the hulls of those little M-3's and out the other side. If they hit that little aluminum transmission, the transmission exploded, and everyone got hurt. We didn't have much protection." The 1st PTG was not issued the M4A4 Sherman medium tanks (with 75mm guns) until April 1944. even then, there were only enough Sherman's for a medium tank platoon, attached to both battalions. The Chinese also were allotted more Sherman's for both of their battalions. The Sherman's' 75mm gun provided adequate firepower against Japanese armor and AT guns.

The 1st PTG usually worked closely with the Chinese 22nd Division. There were liaison officers assigned both Allied units. As with many Chinese units, the 22nd Division had a poor combat record. In this regard, the 22nd Division was typical of many Chinese units, which, despite modern equipment, training, and support were reluctant to engage the Japanese. Dilatory advances were a Chinese Army specialty. Consequently, Japanese forces continually turned the flanks of Chinese forces.

General Stilwell was well aware of the problems with Chinese Army. When he arrived in March 1942, he learned the Chinese lacked everything. Organizationally, it was an Army of over 300 divisions, but with each division having an average T.O. of 5,000 instead of 10,000. The troops were ill trained, provided with old and inadequate equipment, underfed, and unpaid. A substantial number of officers were more loyal to local provincial warlords than to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Many Chinese Divisions had never seen combat and had no desire to break the undeclared truce that was in effect when Stilwell arrived in theater in 1942. Stilwell himself was an obstacle to a working Sino-American relationship. Even though he spoke and wrote Chinese, he continually belittled their efforts. He referred to Chiang as a "little peanut" privately and publicly. Stilwell had no grasp of politics either. He failed to understand that Chiang was husbanding his forces for the inevitable conflict with the Chinese Communists.

|

One of Stilwell's main goals was to form select Chinese units into an American trained and supplied elite fighting force and capture main towns. Stilwell, and the Allied staff of the Northern Combat Area Command, believed that the overland key to the relief of China was through Burma. However, Stilwell's goal was side tracked as he was driven from Burma in May 1942, with the 22nd and 38th Chinese Infantry Divisions.

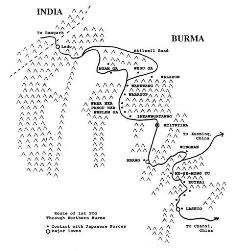

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

The 1st PTG (minus the 1st Assault Gun Battery) left Ramgarh on December 23, 1943 for Ledo, and arrived there a week later. The advance detachment of 44 men from the 527th Ordnance Co. moved out with the 1st Tank Battalion (Provisional) as the American contingent. The 2nd Tank Battalion (Provisional) remained at Ramgarh while awaiting the balance of its personnel and Group HQ and the 1st battalion encamped at Namchik Alli. The widespread lack of armor training among its personnel prompted both battalions to institute crash training programs. The vast majority of the 44 man contingent did not have an armor MOS. When they volunteered, the men believed that they were going to train the Chinese tankers and armored infantry battalions.

On January 11, 1944, Group HQ and the 1st Tank Battalion began a 100-mile, 96-hour road march on the Ledo Road, over the Patkai Range, in a monsoon, to Shingbwiyang, Burma. Chinese and American forces were fighting against an impenetrable Japanese roadblock. Stilwell had directed Brown to take his tank unit as a morale boost. T/5 Homer Richards, an original member of the 527th Ordnance, recalled, "The 1st PTG had great difficulty moving through the jungle. There were landslides and heavy rain. We were right behind the engineers building the Ledo Road. There were Caterpillar bulldozers, graders and tornepoles. These tornepoles picked up huge buckets full of gravel and swiftly dumped it. They traveled about 25-30 miles per hour." The Ledo Road engineering project, also known as "Pick's Pike" (after the Engineers' C.O. Col. Lewis A. Pick) was the greatest engineering feat in the history of the U.S. Army. It turned out to be a 507 mile long road from Ledo, India to Wanting, China, connecting with the Burma Road. The road building continued until slowed by monsoons which dropped an average of 100 inches of rain in a six month period.

Richards also said, "The 527th was well-equipped with machines shops, 6x6's and lathes. We performed all the maintenance in the field, even the jobs that were ordinarily sent to the rear. We had to leave the lathes behind in secured areas when we moved. We had one Chinese lad who traveled with us. He used his fingers as a micrometer and two of them were an exact necessary measurement.

After arriving at Shingbwiyang, a month was spent performing maintenance and road reconnaissance in the direction of Taipha Ga, in preparation for supporting the Chinese 22nd Division. After determining a safe route and fording the Tanai River, the 1st PTG arrived at Lakyen Ga on March 1, 1944. The 1st Tank Battalion crossed the Kumon range over 6,100 foot Nallra Hikyet Pass, turned south and headed toward Myitkyina, population 8,000, with valuable rail lines and an airport.

Sergeant Joe Crawford's Tank No.7 and crew in China. Left to right they are: Dansell B. Moon (loader); George

Byrd (gunner); William S. Burgess (bow gunner); Howard Diskel (driver) and Sgt. Crawford.

Sergeant Joe Crawford's Tank No.7 and crew in China. Left to right they are: Dansell B. Moon (loader); George

Byrd (gunner); William S. Burgess (bow gunner); Howard Diskel (driver) and Sgt. Crawford.

|

On March 3, near Maingkwan, a short distance from Layken Ga, the 1st Tank Battalion experienced the first contact with Japanese forces. Reconnaissance information had disclosed that the Japanese were conducting small patrols in the area. The tankers, led by Col. Brown, filed behind the two armored bulldozers forcing a 20 mile path through the dense jungle. Some of the Chinese tankers had less than a day's worth of driver's training.

That night, without reconnaissance, the tankers ran into Japanese forces. One of the armored bulldozers was the first casualty, and then the Japanese found the Chinese armored infantry. Fierce combat ensued. Two of the Chinese-crewed tanks fell into the Idi River. The Japanese opened up with large-bore artillery, 75mm guns, 47mm AT, mortars, as well as automatic weapons fire. Col. Brown was able to direct his remaining tanks into a lager, muzzles aimed outward. It was now obvious that the Japanese force was probably battalion size, preparing for an assault against the Ledo Road. Four times, Col. Brown attempted to radio the information to Northern Burma Combat HQ, and four times his antenna was shot away. He was finally successful on his fifth attempt.

The Chinese armored infantry were taking heavy casualties, yet accurately returned fire. The Japanese assault force was broken and they withdrew at daylight. The two Chinese M3A3's were dredged from the river and repaired. Japanese snipers followed the tankers as they also returned to evacuate their casualties.

Several of the veterans recalled that night. T/3 Lennie House, one of the casualties, recalled the events of March 3, 1944. "I was a gunner in one of those little M3A3's. My tank was named Willa Dean, after my fianc e. I had her name painted on the front of the hull and her photograph with me in the tank. Earlier in the day, neat Ngam Ga, the Japanese 18th Division had hidden in the tall elephant grass and tried to burn us out. We were setting up our night defensive position, and digging a trench for a machine gun. We were all out of our tank, and at 1830 hours the Japanese opened up on us with long range artillery and mortars. We had a couple of Americans and several Chinese killed, along with several wounded. I was hit in my hands, arms, legs, and everywhere else by shrapnel. I laid out there all night. We didn't move until the next morning, when some P-51's flew as cover for us. The KIAs and WIAs were tied to tanks and we withdrew. After a miles, I was loaded onto a jeep and carried another mile. I was operated on and transferred to the 20th General Hospital at Assam. I was in various hospitals, for my wounds, a total of 14 months, until I was discharged in May 1945.

M/Sgt. Carl Beck, part of the 527th advisors, recalled that "Here we were, out in the field with almost no armor training, trying to teach the Chinese. We were ambushed by mortars and detonated some mines. Two guys in my tank, a radio operator and the lieutenant, were both killed by shrapnel from the mortars. We were surrounded and in danger of being overrun. We were having difficulty in telling our Chinese allies apart from the Japanese. I tied the KIAs to my tank, and moved some of the wounded inside. We had a lot of casualties in a short time. We made a 4 mile dash through the Japanese forces to the safety of our lines. We were shot at continuously. I'll never forget that night - it was the first combat I saw." The ambush claimed nine American casualties - four KIA - and four light tanks.

|

The monsoons had stopped, so the road conditions had improved for the Group. Another difficulty was becoming more readily apparent. The Group was encountering the first of its problems with the Chinese soldiers. Sgt Leonard Farley, a tank driver attached to the 1st Tank Battalion recalled, "Near Walawbum, one night in March 1944, a group of Japanese bombers flew over, crisscrossing, looking for us. We were blacked out and in static positions. The next thing we knew, the Chinese tankers opened up with their tracers, which gave away our position. The Japanese planes bombed us. We didn't receive any casualties, but we weren't happy with our Chinese Allies." Crawford recalled that "The Japanese were also using a 150mm artillery piece that we called "Nervous Nellie."

On March 4, 1944 in support of the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) - "Merrill's Marauders," and the Chinese 22nd Division, the 1st Tank Battalion assaulted the remnants of the Japanese 18th Marine Division, the unit that had captured Singapore and chased Stilwell's forces out of Burma. The 1st Battalion captured Maingkwan by March 6 and headquartered in the center of town. The Japanese 18th Marine Division, led by Lt. Gen. Shinichi Tanaka, had chased Stilwell's forces out of Burma earlier in 1943. General Stilwell, the CBI commander, had been determined for several months to force the Japanese to retreat as far as Stilwell did.

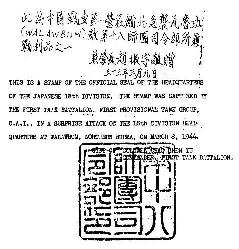

While fighting in several villages near Walawbum, in the Hukawng Valley, from May 3-9, 1944, working with the 5307th the 1st Battalion again ran into the Japanese 18th Marine Division. "Operation End Around" was designed to have the tankers attacking from the west and the 5307th from the east. The tankers cut a supply line near Wesu Ga of the Japanese 56th Regiment which was intended to be used in attacking the 5307th. The 1st tankers fired into the 18th Division HQ at Kumnyen, killing more than 100 Japanese. The 18th Division then retreated, for the first time, leaving most of the valley to the Allies. Even Stilwell rejoiced. The Chinese and American tankers also captured large quantities of enemy equipment for the first time. Their best trophy was the official seal of the 18th Division, which was sent to Chiang.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

Even while withdrawing, the Japanese kept up the pressure. They set booby traps, burned the jungle in front of the tanks, and tried mines. From Walawbum through Jambu Ga, enroute to Shadazup, the 1st Battalion was ambushed by Japanese Marines and lost three light tanks. Cpl. David Quaid, a member of the 5307th recalled that he and "Newsreel Wong" (the photographer famous for photographing the crying Chinese baby during the Japanese bombing of Shanghai) ventured up to Jambu Ga. "We saw that the M3's had crossed over what we called the 'Combat Trace' - it was a Japanese supply line. There were some tall trees next to the trace. The Japanese had jumped out of the trees with 6" x 1" blocks of picric acid formed from Japanese hand grenade powder and using their bodies as tampers, had blown themselves up and blown holes in the tanks." The next day the 1st Battalion lost five more light tanks due to magnetic mines.

While the 1st Battalion was engaging the Japanese forces, Group HQ arrived in Burma. New U.S. officers and a new Chinese commanding officer were added at Kumhyen Ga. Group HQ then moved up to Shadazup and joined the 1st Battalion. During this time, several attempts were made to contact and support elements of the Chinese 22nd Division, but jungle and other difficult terrain made for limited operations. The jungle canopy and the steep hill terrain in Burma also "affected communications between armored units and HQ, but not tank-to-tank," according to Farley. Another problem was, as several veterans put it, "The Chinese armored infantry units did not want to coordinate their attacks with their tanks. Since the armored infantry did not want to support their armor, their armor did not want to spearhead any attacks."

Farley said, "All the training the 1st Battalion had regarding armor tactics went out the window once we moved off into the jungle." When assaulting Japanese positions, the tankers were unable to maintain the armored formations they had been taught to use. The Japanese knew that the tanks had to stay on the narrow roads because of the jungle. Dust raised by the vehicles gave the tankers' movements away even if the foliage muted it. The Japanese concentrated their artillery and guns on open areas. Bickel recalled, "One of the Japanese tactics was to cut down trees directly in front of their gun emplacements. The stumps were left higher and unsuspecting tanks could get stuck."

Crawford recalled that "General Stilwell showed up at the front one day, when the Japanese were retreating with their heavy artillery. He directed the Chinese tankers to assault the retreating enemy. The Chinese moved too slowly and the Japanese escaped. Stilwell told Brown that he wanted an American tank platoon organized. We were assigned 12 M4A4 Sherman's. Five went to the U.S. forces and the others went to the Chinese."

Bickel's recollection of this particular day was "The Chinese were not aggressive. On one of our so-called combined assaults made against a Japanese position, U.S. tankers moved through the Japanese and continued to where we were three miles behind Japanese lines. When we returned, the Chinese had not moved one foot. Grinning Chinese held up their hands, making the "V" for Victory sign with their fingers, which angered us."

|

On April 19, 1944 the 1st Battalion received the first shipment of 12 M4A4 Sherman tanks. The tanks had been shipped by rail from Calcutta to Assam, under the direction of the 705th Railway Grand Division. This Medium Tank Platoon was commanded by Lt. Richard F. Doran. In addition to training with the Sherman's themselves, the Americans began training Chinese crews in operation of the tanks. The Sherman's had five 6 cylinder Chrysler engines synchronized to one flywheel. "It was tough to maintain the necessary synchronization," said Richards. His task was repair and re-arming of the tanks' 30 cal and 50 cal machine guns. During the monsoons, the Group had difficulty in obtaining supplies, some ammo, and parts. "Everything came to a halt during the monsoons, but we always had oil," said Richards. "We had enough 75mm and 37mm ammo to train with, even during the monsoons."

Farley found himself fortunate enough to have been assigned to a Sherman, and thought the "armor protection" of the Sherman to be its best asset. Farley recalled seeing one captured Japanese tank, and found it inadequate when compared to the Sherman. "In any case, we didn't have any armor battles like they did in other theaters," said Farley.

Group HQ, the 1st Battalion, and the American Medium Tank Platoon convoyed to Warazup on April 28, departing two weeks later. During this period, coordinated air, artillery and armored attacks were made against Japanese forces, organized with unanticipated heavy anti-tank defenses, along the Pangyu Hka (river), Inkawngatawng, Hwelon Hka and at Malakawng. American casualties totaled 2 KIA's, 4 WIA, four light tanks and one medium tank, from all three locations. It was also noted that the Chinese infantry failed to occupy captured ground, stranding the tanks. Richards said, "At Hwelon Hka, the 1st Battalion led the way. A couple of Jap tanks managed to escape out of the back door there."

Several veterans recalled the assault at Inkawngatawng. As usual the Battalion bypassed several rickety truck bridges to reach its target. Bickel's Sherman had a dozer blade added to the hull front, and he was carving out approaches to rivers on both sides. He described it as, "Quite a task while peering through a periscope." Once near, Lt. Doran ordered all the tanks to move off to the right of the road and form up in a wedge. The tankers could clearly see across a half mile barren patch of ground. Once tall elephant grass had covered the field, but now all the grass was ankle-deep, charred and offered no cover at all. At the far end of the field was jungle - and the Japanese were waiting. As the tanks moved forward, Lt. Doran directed them into a line.

As Lt. R. W. Field's Sherman named Patsy Ann moved up, the tank detonated a mine and damaged a tread. Unknown to the crew, a Japanese Marine then jumped onto the tank, and attempted to affix a magnetic mine. Pvt. Bernard Nelson, the gunner in another Sherman, named Tokyo Limited, spotted the marine and shot him from the tank. Tokyo Bar, a Sherman commanded by Sgt. A. K. Yee, a Chinese-American, had a Japanese 47mm round go right through the barrel of his 75mm gun.

Sgt. David B. Richardson, the most highly decorated U.S. Army war correspondent, recalled how he became a temporary member of the 1st PTG. "I was a correspondent for Yank magazine, and I unknowingly wandered into the briefing for the 1st PTG's combat assault at Inkawngatawng. I told Col. Brown that I was a correspondent and wanted to write a first-person account about his unit. Well, they were going out immediately, and as was the case on prior occasions, I'm sure he thought I was only an observer. I had already been a waist gunner on a B-24 that had been attacked by four Japanese Zeros, so I told him that I was a machine-gunner. I figured that all I had to do was squeeze the trigger and sight by tracers. I also thought that I'd be crewing on a rear guard tank."

"Well, Col. Brown told me that I was the gunner on the lead tank! It seemed the original fellow came down with a case of dysentery. I hoped that I'd be okay in the role."

|

"We approached the target and heard the Japanese return fire bouncing off the front of the tank, named Tokyo Hearse. Every once in awhile, the Japanese threw something bigger at us, and the little light tank stopped. We would restart the tank and I started shooting long, uncontrolled bursts. One of the other crewman told me, 'just short bursts, along the line where you see the sparks coming from. If you see a big orange spark, that's an AT gun, and aim for them first. They can hurt us.'"

"So I started shooting these short bursts at the sparks. It was hard because we were moving and I was looking out this small slit. Then, I found out why tank gunners wore gloves and goggles. Those spent shells came right back at me, and boy, were they hot when they hit your skin and eyes. I sure was blinking a lot too. We took the objective."

"Afterwards, we had a debriefing. Brown, who had been circling overhead in an L-5, called out, 'Who was that gunner in the lead tank?' I thought I had screwed up. Instead, Brown verbally commended me, saying that I had done a good job of keeping their heads pinned down by my accurate fire. Boy, I sure felt better after hearing that. I never told anyone that I was blinking and shooting with my eyes shut."

Crawford was a 75mm gunner in Tokyo Limited. "My tank took 12 hits at Inkawngatawng, but there was no damage from the 47mm AT guns." Brown ordered air cover but the weather was bad for 4 days. When the weather cleared, and with air cover, the 1st PTG went back and crossed the river. Crawford also recalled that "We could smell the dead Japanese from inside our tanks. We crossed into rice paddies that also had tall elephant grass. There were a few M3A#'s, manned by U.S. troops, who were advising the Chinese. One of the tanks was hit and burned. My loader and I sat on the back of our tank, holding one of the severely burned tankers, while we transported him back to receive medical aid. The next day Brown held a memorial service for the members of the tank crew. I recall seeing streaks of ash and burned bones in the tank - all that was left of the crew members."

Several unsuccessful attempts were made to deliver the tanks to Myitkyina before the summer monsoon in order to support the 5307th. Early in June, with the advent of the monsoon, the 1st Battalion was ordered to move to a training area. Reconnaissance was made by Col. Brown and the engineer platoon to locate a suitable training area. The village of Rangdoi on the Brahmaputra River in northern Assam was selected. The engineers were also tasked to improve the Saikhoa Ghat-Rangdoi Road.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion, which had remained at Ramgarh since activation, began moving up to join the rest of the Group. It moved by rail and convoy to the Ledo Road. When it proved impractical to move into Burma during the summer monsoon, the 2nd Battalion was ordered to Rangdoi to meet the 1st Battalion and begin training.

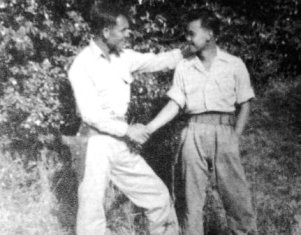

Sgt. Joe Crawford with U.S. educated Tuan Mo Ming, who was assigned to the Chinese Army complement of the 1st Tank

Battalion.

Sgt. Joe Crawford with U.S. educated Tuan Mo Ming, who was assigned to the Chinese Army complement of the 1st Tank

Battalion.

|

Training schedules were drawn up early in June 1944, and the training commenced as personnel and equipment arrived, and the weather permitted. The training included all phases of gunnery, from the M-1 rifles to the 37mm and 75mm tank guns, armored formations, reconnaissance, and road marches. Early in August the 1st Assault Gun Battery arrived at Ringdoi, which allowed for the coordinated training of the artillery and tanks. Indirect firing of 75mm gun was offered. Plans were executed to officially attach the entire compliment of men from the 527th Ordnance to the 1st PTG. On September 22, 1944, the 527th was formally assigned to the 1st PTG from Northern Combat Area Command. Road reconnaissance continued on a routine basis.

Chinese Army Lts. Chao Shin and Hunag Te Hsin were authorized to organize Chinese Engineer and Reconnaissance platoons to work in coordination with their American counterparts. Chinese mechanics were taught tank repair by their allies from the 527th Ordnance.

The Group spent the monsoon season training in armored field artillery tactics and did not move out again until early November. They left Rangdoi by convoy, and passed Ledo and Myitkyina and arrived at Pangkam ten weeks later. They had traveled approximately 659 miles.

While at a USO show on January 24, 1945, near Bhamo, the men of the Medium Tank Platoon first heard heavy machine gun fire and then an announcement over the show's loudspeakers. They were directed to return to their bivouac area. When they did, they found the mechanics had all their tanks running. The tankers learned that the first convoy into China had run into Japanese forces.

Crawford was the fourth tank on the Burma Road, now officially open. He said the Ex-CBI Roundup had an article that was inaccurate because it indicated there were no U.S. troops there at the time. Shortly afterward, they heard that there was a Japanese counterattack, so they were ordered to attack them. It turned out that they were only Chinese troops returning for supplies.

Immediately after this misinformation, the Medium Tank Platoon was ordered south to support the Mars Task Force (475th Infantry), who were pinned down on a southern stretch of the Burma Road. The 475th had heavy casualties. When the platoon arrived, the Japanese retreated, but the infantrymen were grateful for the arrival of the tankers. The tankers remained with the Mars Task Force for 2-3 days, but there was no enemy action.

Crawford, now tank commander of No.7 said, "My tank was having problems with the spark plugs. The tank was constantly backfiring while going over hills, and it even caused the engine to catch fire once or twice."

|

On January 27, 1945 the American Tank Platoon and Reconnaissance Platoon led the attack on Japanese forces near the village of Mu-se-Mong Yu, Burma. The Japanese roadblock was destroyed and the Stilwell Road was again reopened for convoys. Two days later, the American units along with the Chinese 3rd Tank Company (1st Tank Battalion) met the Japanese, this time near the town of Kutkai. For only the second time in theater, the tankers engaged Japanese armor. This time, unlike at Hwelon Hka, the Japanese came away bloodied. Two Japanese light tanks and on Japanese medium tank were destroyed. Four Americans were wounded and one light tank was damaged.

Crawford recalled that "The Medium Tank Platoon and the Reconnaissance Platoon were directed up the sides of a hill near Kutkai, to recon the nearby village. The Reconnaissance Platoon split of from the M4A4's and took the flank. Except for the hills, the terrain was rice paddies and tall grass. While driving on a narrow road on a steep hill, I noted three brush piles in the paddies. Everyone had their heads and shoulders exposed out of the hatches. At that time, three Japanese tanks, camouflaged in the brush piles, opened fire on the tank column. My tank radioed to S/Sgt. Szura that we were being fired upon. Szura was already aware of it and so was Col. Brown, flying above them in a spotter plane. He directed the tankers to return fire, which we all did. My tank now had starter problems, and stalled out on a curve, above the Japanese tanks. Szura attached a tow cable to my tank and pulled us out of the line of fire - my tank couldn't depress the barrel enough, and was a target. Both Szura and I exited our tanks and got my M4A4 started, and then we joined the assault. My tank was struck by Japanese fire - it made a hole about the size of a match head. The other U.S. tanks opened fire and burned one Japanese tank and crippled two others, which were removed under cover of darkness. The tank that was destroyed was smaller than the M3A3's.

T/4 Ted Janas was the driver of an M3A3 named Stevie. "Szura was my tank commander. We pulled Crawford's tank out of the line of fire and then Stevie returned fire with the other tanks. Those Japanese tanks were so light, it was like shooting cardboard. I recovered a Japanese meatball flag from one of the tanks, and sent it home."

The Group continued supporting the New Chinese First Army in the vicinity of Lashio. The Medium Tank Platoon was attached to the 612th and 613th Field Artillery battalions (75mm Pack Howitzer) near Lashio, in support of Chinese 1st Army units. The platoon now had an additional 6th M4A4 tank, and they were all dug in on a hillside. They had difficulty zeroing in on their targets, and Lt. Choate, the aerial artillery observer, was losing patience with them. Every time they fired a round, the tanks moved about 18 inches, effecting the firing accuracy. The solution to the problem - repositioning the tanks on flat terrain - was simple and effective, and the AO was soon accurately directing their fire over the heads of the Chinese infantry and into the Japanese lines. Near Lashio, the tankers knocked out 13 of 14 Japanese trucks at a gas supply dump. Near the railroad station, the tankers left over 100 dead Japanese from their accurate fire. Bickel said, "We fired 12 rounds every three seconds for approximately 20 minutes at a time and then changed our position. We fired through the night and again the next day." Crawford said, "We had intercepted Japanese radio transmissions in which the Japanese complained that the Americans had 'automatic artillery fire'." Bickel thought it was the infamous "Tokyo Rose" who broadcast the quote concerning "automatic artillery fire."

Replaced in Lashio by elements of the British Army, the Group deployed to Kunming, China on June 13, 1945. Brown was replaced by his deputy commander, Lt. Col. McPherson LeMoyne. Brown was appointed the new director of the Tank School at Fort Knox.

|

The Americans in the 1st PTG were continuing to perform maintenance for both armies. Richards recalled, "Picking up tank engines at Myitkyina and Assam, I could get 6 tank engines in a 6x6 truck." Traveling in China was considerably easier, according to Richards. "We traveled 1,034 miles in only 13 days to Kunming. China was hilly but there were a lot of rice paddies. From Kunming, the tankers convoyed to Chanyi. China was not as heavily forested as Burma, so armored vehicles were more mobile. Additionally, the wider tracks of U.S. armor proved not to be nearly so road-bound as was Axis armor.

"During the latter part of July, and the beginning of August, 1945, the 1st PTG was gearing up towards the coast," recalled Farley. "We were based at Chanyi, China. The rumors were that we were going to support an amphibious assault onto the China coast, and attack the Japanese ground forces from their rear. The atomic bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki put an end to the rumors."

At Chanyi, the Group turned over all of its equipment to the Chinese, and U.S. personnel began rotating home. Farley recalled that "The Sherman's were turned over at gunpoint to the Chinese. It was hairy there for awhile, but cooler heads prevailed." The Group was formally deactivated on December 18, 1945. The Chinese tankers of the First, Second, and Third Battalions reformed as a separate armored force under the Nationalist Chinese banner. The unit was lost near the Marco Polo Bridge in 1949 against Chinese Communist forces.

Richards recalled some of the medical problems he suffered. "Leeches were a constant problem in Burma," said Richards. "Had to burn 'em off with cigarettes, no matter where they were on your body." He caught malaria, despite taking atabrine 3 times a day to prevent it, like we were supposed to do. Came back with yellow eyeballs - they looked like the yellow pages in the telephone book - and it took me about 5 years to completely recover from the malaria."

"We took our atabrine and slept in net-covered hammocks. I never was sick once," said Farley. Bickel recalled that "One day I inadvertently drove into a red ant hill. These ants are approximately 1/2" long and were capable of drawing blood with their jaws. The ant armies invaded our tank, and the crew was really scratching. I was not a real popular driver for a while.

The men who served under Brown recalled that he was a front-line fighter, like Stilwell, and a leader. If Brown wasn't in the air in an L-5 observation plane, directing his tankers in combat, he was on the ground leading reconnaissance mission in an M3A3, rather than a Sherman. He used the light tank so that another crew could have the heavier Sherman, according to a few vets. Stilwell told Brown several times to remain in the rear, as he was a valuable asset. However, Brown ignored his close friend. Stilwell was known for having taken the same chances, in an effort to encourage his Chinese soldiers, or embarrass their officers, lest any harm come to him. Brown was a firm believer in training, often ignoring poor weather conditions. Like Stilwell, Brown was the only other American officer authorized by Chiang to lead Chinese troops in combat. Brown was also known for publicly supporting the Chinese combat effort.

The veterans of the 1st PTG were uniformly proud of their service, and considered it as important as any other unit in the CBI Theater.

|

|

Click to learn more about the 1st Provisional Tank Group

TANKS INSIGNIA ROUTE THROUGH BURMA CAPTURED SEAL |