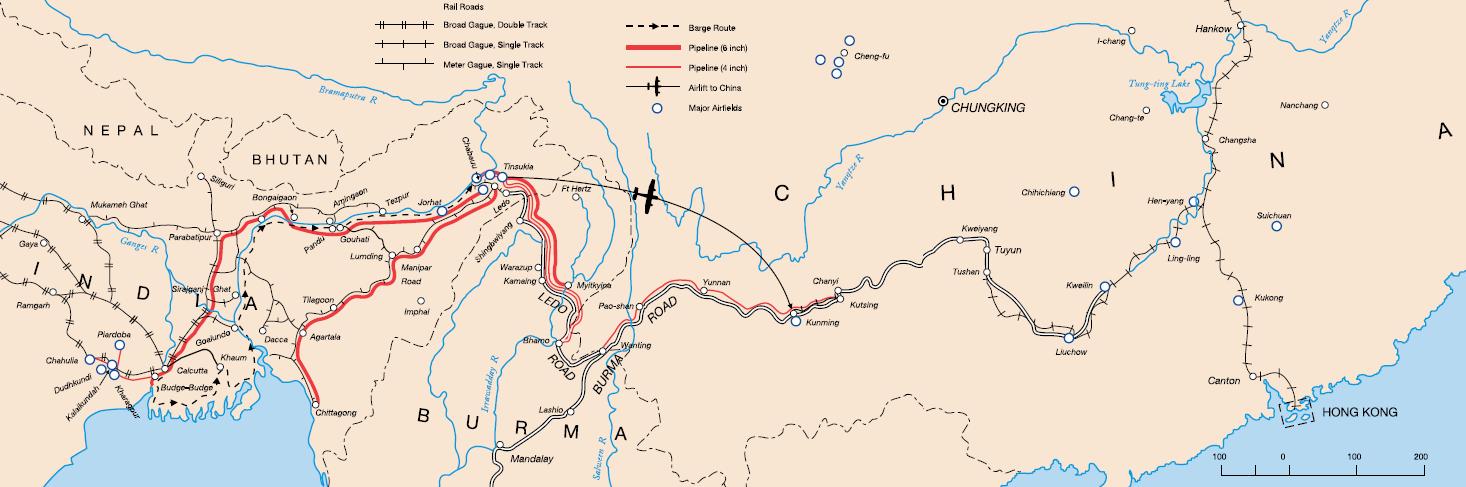

China-Burma-India Theater China-Burma-India TheaterLines of Communication |

by Lt. Col. Joseph B. Shupe, USA (ret.)

Lines of Communication: A network of routes for sending messages and transporting troops and supplies.

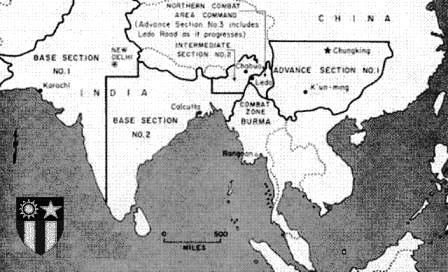

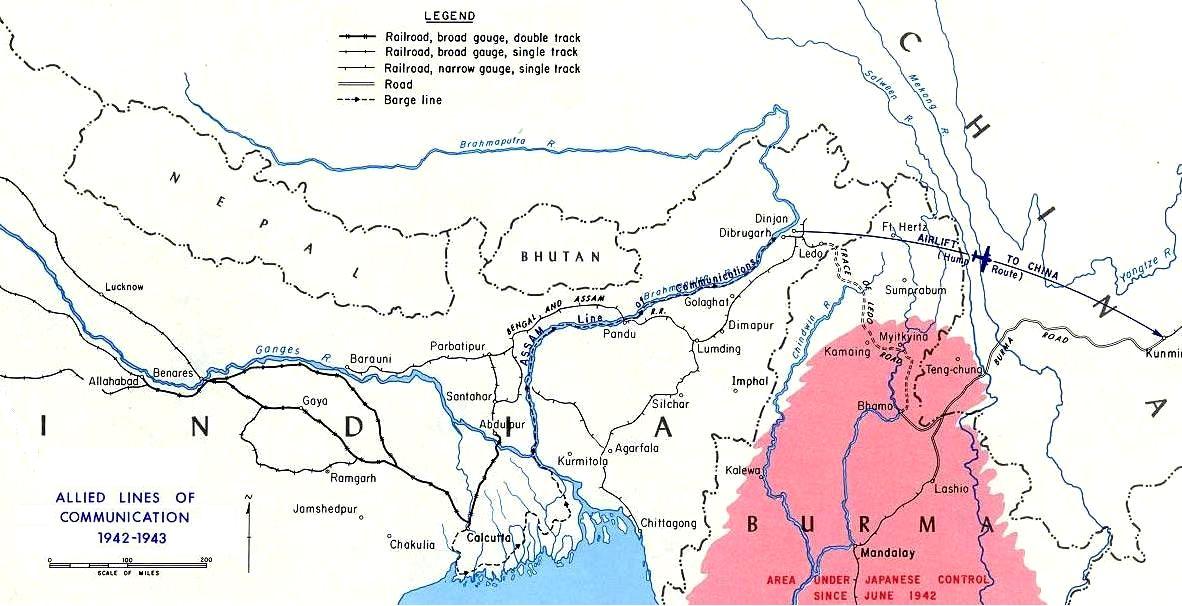

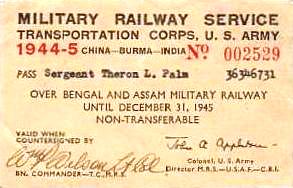

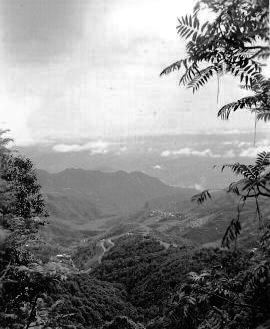

OVERVIEW When the Japanese cut the Burma Road, the only alternative to supply China was via the air route over the Hump. From the outset, transportation loomed as a major problem in order to keep China in the war (the main mission). Indian ports were limited and were unable to handle greatly expanded traffic. Also, the highway system (except on the northwest frontier) was undeveloped; ports were served mainly by rail, coastline shipping, and river transportation. When Assam became the scene of airfield construction and combat forces moved into Burma, transportation in that area was very deficient. It was first necessary to use ports on the west coast of India because those in the east were blocked by the Japanese. As a result, supplies had to be moved 2,100 to 3,000 miles to Assam; first by rail, then by air to Kunming.Within China they had to be moved to Chungking and to advanced bases by rail, highway, river, and coolie or animal transport. The Indian railway system was ill-prepared to handle additional traffic. The worst bottleneck was the meter-gauge railway on the eastern frontier; it was limited in capacity and the Brahmaputra River was unbridged. Inland water transport was concentrated mainly on the Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers and their tributaries,supplemented by railways in East Bengal and Assam. The tremendous job of organizing lines of communication was given to Brig. Gen. Raymond Wheeler, then heading the Iranian Mission. Gen. Stilwell placed him in command of the Services of Supply (SOS) of the CBI Theater. He arrived in Karachi on March 9, 1942 and established SOS Headquarters there. Three days later, the first contingent to arrive in the CBI were air force troops diverted from Java. Borrowing some of them, as well as some from the Iranian mission, and casuals destined for Stilwell's headquarters,Wheeler got port and other operations underway. In May, he moved his headquarters to New Delhi and divided the SOS organization geographically. Base Section No. 1 in Karachi; Base Section No. 2 in Calcutta; Intermediate Section No. 2 at Dibrugarh (and later at Chabua)Base Section No. 3 at Ledo (the base for projected combat operations in North Burma); Advance Section No. 3 at Kunming (June 1942); later Advanced Section No. 4 at Kweilln for U.S. troops in East China. The two Sections in China were consolidated in January 1944 to form a single SOS agency in China. The U.S. Army, wherever possible, relied on the British for transport within India. Other than air operations, transport activities were confined to base hauling and to small scale port operations at Karachi, Bombay,and later Calcutta. During 1942, Karachi received almost all CBI cargo. Then in October 1942, the U.S. Army assumed responsibility for construction of the Ledo Road. In China, the U.S. Army was almost totally dependent, initially, on the Chinese for land transportation. By early l943, plans were made for a greatly expanded operation to support 100,000 U.S. troops inChina, and a major emphasis on support of an air offensive in China; a goal to move 10,000 tons a month over the Hump by November l943. To do this, supplies were now entering Calcutta, which was emerging as the major American cargo port, but the major bottleneck was the inadequate transport facilities leading to Assam. So, U.S. officials negotiated with the British Planning for rail operations though proved more difficult. Planners wanted to use American troops on the meter-gauge portion of the Bengal and Assam Railway from Assam to Ledo. The British objected but later officials convinced them that if commitments to the Chinese were to be met, this was necessary. Result - a Military Railway Service (MRS) was approved and we took control of the meter-gauge line between Katshar and Ledo, effective May 1. 1944.Meanwhile, additional port troops and equipment arrived in Calcutta; a U.S. barge line was organized; and Inland waterway troops and equipment had been shipped from the U.S. By the time CBI was split into two separate theaters in October 1944. major transportation problems had been overcome in the India-Burma Theater. The once congested Calcutta port was now one of the world's best U.S. Army ports. Capacity targets for the Assam LOC were being exceeded and supplies were flowing smoothly to forward areas, thanks to centralized movement control, the Military Railway Service, U.S. and British pipeline and other construction. The barge equipment though proved unsuitable for the long hauls on the Brahmaputra, but proved useful in Calcutta port operations and for the support of airfields in East Bengal. Karachi now became a minor port, and the Bombay-Port of Also, good progress was made in air deliveries to China. The capture of Myitkyina airfield in May 1944 greatly improved air routes to China. In October 1944, Air Transport Command (ATC) and other air carriers delivered over 35,000 tons to China vs. 8,600 in October 1943. Myitkyina by August 1944 was converted into a forward supply and air base. Transportation activities expanded into early 1945 when the Stilwell Road was opened into China. Hump deliveries reacheda peak of over 73,000 tons by July 1945. The 4-inch pipeline along the Stilwell Road from Ledo to Kunming was opened in June, and China road deliveries were kept near peak levels through the middle of 1945. The Port of Karachi was closed and troop debarkations were transferred from Bombay to Calcutta.Then, by V-J Day, shipments to the India-Burma Theater were curtailed. By October 15, The MRS Railway was turned overto the British and the barge line was abandoned. Hump and pipeline deliveries ended shortly afterwards.SOS in India was inactivated in May 1945 and its functions were assumed by the Theater G-4. INDIAN PORTS When U.S. Army transportation operations began in the CBI early in 1942, the ports available in India were limited. The presence of the enemy within striking distance of the east coast precluded the use of ports in that area. Bombay on the west coast was the main British port and was heavily congested with British traffic. As a result, Karachi on the northwest coast became the first American port. It had 22 ship berths and large ships could be moored in 60 feet of water. Most cargo was unloaded from ship to railway cars with the aid of floating cranes. Since there was no shipside or transit sheds, cargo was transported by rail, truck, or lighter. Upon arrival of the first U.S. troops in March 1942, Gen. Wheeler, SOS commander, set up a provisional port detachment. Their first job was to move 20,000 tons of China lend-lease cargo that was diverted from Singapore and Rangoon. This detachment was replaced in May by two companies of the 393rd Port Battalion. Port operations were under Headquarters Base Section No. 1 of the SOS. During 1942, most U.S. supplies entered through Karachi. The port troops used native coolie labor. During 1942, the port discharged and transshipped 130,342 tons of cargo; in addition to debarking 13,800 troops. As soon as the tactical situation permitted, an east coast port closer to the forward areas was opened. Starting in September 1942, supplies were transshipped from Karachi to Calcutta. The latter was opened to vessels arriving from the U.S. in March 1943 and soon surpassed Karachi in importance. With the shift from Karachi to Calcutta, the two port companies were transferred, one moving in February 1943, the other in August 1943. Continuing port activities at Karachi were handled by a small Army staff supervising native labor, but this did not impair operational efficiency. During 1943 Karachi, on three occasions, stood first among overseas U.S. Army ports in monthly cargo discharge performance, and in December set a new port record for itself, unloading 5,645 tons from the S.S. Mark Hopkins in three days and 10 hours working time. Karachi handled a dwindling traffic load in 1944; after January 1944 it became unimportant as a supply base. The port's outstanding job during the year was the unloading of the Mark Twain with 5,597 tons of cargo within 48.5 hours after docking. Later, the need for an Army port in northwest India gradually disappeared. On May 15, 1945, Base Section No. 1 was inactivated with the exception of a small detachment to unloadsmall shipments from tankers and some coast-wise cargo; then all troops were transferred throughout the CBI. At war's end, Karachi Port was reactivated for debarkation of personnel (August 1945). Many troops were brought in by rail from the Ledo and Chabua areas. As aircraft were withdrawn from the Hump run, they supplemented and latersupplanted the troop trains. The troops were billeted at the Replacement Depot at North Malir, 14 miles from the port, and after processing were trucked to ship-side and embarked. The first troop transport to arrive, the GeneralMcRae on September 22nd, took on 3,008 passengers. Evacuation operations peaked in October when 26,352 troops were loaded on eight transports. The port was closed in January 1946 having embarked 80,185 personnel. Then, all porttroops were either transferred to Calcutta or returned to the U.S. BOMBAY Despite its magnificent deep-water harbor and excellent port facilities, Bombay was overtaxed by British and Indian traffic, and remained so into 1943. As a result, it was not used to handle American cargo. However, since neitherKarachi nor Calcutta could accommodate large transports, Bombay became the major port of debarkation for American troops entering CBI. During 1943, a total of 118,893 Americans passed through the port, including troops for thePersian Gulf Service Command. Initially, American operations were conducted by a small staff from Base Section No. 1, SOS. They made arrangements with the British, who directed the debarkation of troops and the discharge of cargo; providing berthing and staging facilities; and handled the onward rail movements. From Bombay, the troops traveled 1,300 miles by rail to Calcutta, and more than 2,100 miles to East Bengal or Assam. On December 31, 1943, the Bombay Port of Debarkation was formally established with a small number of personnel which gradually grew to 500. The mission was the debarkation of U.S. Army troops from transports which were usually berthed at Ballard Pier. They also processed personnel leaving on American ships and also some coast-wise cargo. Every action had to be cleared with British authorities which Americans found to be unsatisfactory. This caused delays to unloading troops because of lack of rolling stock and poor timing of trains. Gradually, though, one function after another was transferred, so that the U.S. port commander, eventually assumed responsibility for most activities. Reliance on British staging facilities ended in July 1944 when an Americanstaging area was opened at Lake Beale, 125 miles from Bombay, at one of the main trans-India raillway connections. That camp continued until October when a section of Camp Kalyan. a British staging area in Bombay, was made available for personnel departing the Theater. Camp Beale was then assigned to the SOS Replacement Service and was used exclusively as a staging area for troops arriving in CBI. Until late spring of 1944, most U.S. Army troops arrived on British transports after transshipment from War Service Administration (WSA) vessels in the Mediterranean. Thereafter, they were brought in by U.S. Navy transports of the P-2 type. The first of these, the General Butner, arrived In May, followed in July by the General Randall. This was a learning experience for the port commander. By the latter part of 1944. the Bombay port operation was proceeding satisfactorily. The poor timing of the arrival of troop trains at quayside persisted, but this was steadily improved. The goal was to insure a five-day turnaround for the ships, although the wait for convoy escorts occasionally extended the time to seven days. American operations were ended when the British wanted exclusive use of the port for anticipated post V-E Day redeployment of their troops to India. After a successful trial run for two American transports to Calcutta in February1945, it was decided to give up the Bombay port. The last transport to arrive at Bombay, the Admiral Benson late in March, debarked 4,866 troops and took on 1,363 passengers. All debarkation activities were then shifted to Calcutta, and on June 1st, Bombay was officially closed as an American port. CALCUTTA Calcutta is located in Bengal Province, 80 miles up the Hooghly River. The river followed a winding course and was relatively shallow, accommodating ships with a draft of 22 to 30 feet, depending on the season. It had 49 berths, most of which could accommodate ocean going vessels, and 44 ships could be anchored in the stream. The more modern ofthese faculties, the King George and the Kiddepore Docks, were inside the tidal locks. Most wharves were equipped withtransit sheds, and there was a fair amount of shore and floating equipment. The port was served by three broad-gauge rail lines; the Bengal and Assam Railway having tracks into the docks. The labor supply was ample. Proximity of the enemy precluded its use earlier, but by the end of 1942, six small vessels under the supervision of a U.S. Army Engineer unit. had been discharged. Port operations began to expand when upon the recommendation of the Anglo-American Shipping Mission, shipping wasrouted directly from the U.S. to Calcutta. About 8,000 tons of U.S. Army and China-aid supplies arrived in March 1943,and incoming tonnage mounted steadily thereafter. The two port companies from Karachi (540th and 541st) tookover operations. The King George Docks were used mainly, and also the Kiddepore Docks. The port troops supervised coolie labor and in an effort to unload maximum tonnage, they operated in 12 hour shifts and worked as long as 18hours at a stretch. As the work load increased, and insufficient personnel were on hand, ships arriving from Colombo, Ceylon, had to bebunched in convoys, and thus delayed from 3-10 days awaiting berths. At the same time, the inability of the Assam Line of Communication (LOC) to carry the cargo, caused an accumulation of freight at the docks and warehouses. This congestion, in the latter part of 1943, handicapped projected military operations. Relief came in late December 1943 and early January 1944. when two port battalions (the 497th and 408th),a total of eight port companies, arrived. As the new port troops tackled the congestion problem at Calcutta, arrangements were made to discontinue convoys from Colombo temporarily to relieve the pressure. Madras was then opened as a sub-port to which overflow trafficcould be diverted from Calcutta. Gradually the amount of cargo discharged monthly more than doubled in January 1944,and in February totaled 128,397 tons, a record for the year. By March, the bottleneck was broken. Between June and October the maximum time lost waiting for a berth was one day.This was helped when American barge equipment and low-bed trailers and tractors were received, and the Assam LOC increased its ability to move supplies up to forward areas. During 1944, the port handled most American cargo arriving in the CBI (1,092,625 vs. Karachi's under 100,000 tons). Calcutta played an important role in making the CBI the leader in U.S. Army port discharge performance throughout overseas theaters. Increased cargo arrivals, beginning in November 1944, resulted in further expansion of port activities; they peaked in March 1945, when 173,441 tons were discharged from 66 vessels. After March 1945, monthly cargo arrivals fell off although still greater than most of 1944. Except that in May, a large number of British and foreign vessels arrived in preparation for the Rangoon operation. Cargo discharged from June - September 1945 averaged 122,549 tons a month, and in July they set a new theater record discharging 3,034 tons in 30 hours.The one large loading operation before the end of the war was the transfer of the XXth Bomber Command to the Pacific. This Involved 10,257 men and loading 10 cargo ships with 13,932 tons of cargo and 2,291 vehicles. Meanwhile, Calcutta had taken over the theater's debarkation and embarkation activities. After their successful experimental run, two C-4's arrived there on April 27. 1945, and anchored in the stream; 5,752 troops were ferried to Princep Ghat and loaded on trains. Embarking troops were then ferried to the ships and were all aboard on May 6. Procedures were improved as successive troopships arrived, but selection of Shaltmar Siding for embarkation proved unfortunate since troops had to carry their duffle bags a quarter mile before reaching the ferry. Later, the Princep Ghat was used and improvements were made when transports came aside the jetties and delivered personnel directly to shore without the use of ferries. To deal with delays in obtaining trains, troops were then moved by river steamer from Princep Ghat to Kanchrapara staging area. Later, such movements were made by truck. Towards the end of the war efforts were made to ship troops aboard cargo vessels as well as troop transports. From May 20 - September 2, 1945, a total of 17,666 troops embarked at Calcutta with 16,028 debarked. With war's end the flow of traffic into Calcutta was reversed. Eleven of 29 ships enroute to CBI were returned to the U.S. and three were diverted to Shanghai. Cargo and troop arrivals at Calcutta declined sharply in September and were negligible thereafter. At the same time, personnel being evacuated from China and all parts of India and Burma began moving into the Calcutta area. The main postwar cargo operations involved the shipment of petroleum products and general cargo to the newly-opened port of Shanghai; the dumping at sea of deteriorating ammunition and chemical warfare toxics; and the return to the U.S. of all other materials. By the end of February 1946, most of the faculties at the King George Docks were returnedto the Calcutta Port Trust. From the start of October 1945 through April 1946, a total of 320,437 tons was shipped to the U.S., Shanghai, or to other overseas areas. In the meantime, Calcutta had joined Karachi in evacuation of troops. The first ship, the General Black, arrived on September 26, 1945 and took on 3,005 passengers. Subsequent arrivals were either other C-4 "General" troopships or smaller WSA "Marine" vessels capable of carrying about 2,500 passengers.Transports were generally berthed at Princep Ghat or the Man-of-War Mooring. Embarkation activities reached a peak in November when 21,990 embarked on eight transports. The closing of Karachi port in January 1946 kept Calcutta busy for another month. By the end of April, 187,761 troops had departed the Theater by water. Of these, 197,576 left from Calcutta. The final embarkation took place on May 30, when 812 passengers boarded the Marine Jumper. MADRAS AND COLOMBO These ports were used at first as emergency ports to lighten vessels whose draft did not permit entrance into the Hooghly River. Madras was opened as a sub-port of Calcutta in February 1944 to handle overflow shipping. Afterdischarging 24,363 tons in February and March, the port received only minor tonnages. These were limited to lightening of vessels and the discharge of small coastwise shipments. Another minor American port was established at Colombo following the transfer of the Southeast Asia Command Headquartersfrom New Delhi to Kandy, Ceylon. It was used for the discharge of cargo for U.S. Army personnel. By October 1945, cargo arrivals had ceased. THE ASSAM LINE OF COMMUNICATIONS The transportation system leading from Calcutta into Assam, called the Assam Line of Communications (LOC), was described by an Army logistician in the War Department as "The most fascinating and complex problem we have in the world." It consisted of rail, water, rail-water, water-rail, and to a limited extent, rail-highway routes. Traffic over the MRS line continued to Increase into the first months of 1945. At Parbatipur, the arrival of modem cargo handling equipment enabled the MRS to increase the number of wagons trans-shipped from 13,470 in October 1944, to 26,796 in May 1945. Operations were further improved with the arrival of additional U.S. equipment. By May 1945, 263 out of444 locomotives were U.S. made, plus 10,113 freight cars. After August, rail movements, with the exception of westwardmovement of evacuated troops, fell off sharply. The MRS troops were evacuated starting late August 1945, and transfer of the line to the Bengal and Assam Railroad was completed by October 15. The Bengal and Assam Railroad was the main carrier on the LOC. Supplies were shipped from Calcutta over a broad-gauge line 200 and 275 miles respectively to Santahar and Parbatipur. They were the principle points for transfer frombroad-gauge to meter gauge railroads. The rail wagons then moved to the Brahmaputra River where they were ferried across, and then proceeded to Tinsukia, whence they traveled over the short meter-gauge Dibru-Sadiya Railroad to Ledo,576 miles from Parbatipur. The railroads were supplemented by two steamship lines, which hauled supplies approximately 1,100 miles up the Brahmaputra from Calcutta to Dibrugarh in Assam. The river and rail systems were closely intertwined and there were numerous junctions along the route where supplies might be shipped by rail to Goalundo, barged to Dhubri or Neamati, and thence proceeded by rail to final destination. There was no all-weather through highway from Calcutta to Assam. A motor road, however, did extend eastward from Siliguri at the northern terminus of the Bengal and Assam RR, through Bongaigaon to Jogighopa. From this point, vehicles could be ferried across the Brahmaputra and then proceed over the Assam Truck Road to Chabua and Ledo. Late in 1943, a limited convoy operation was in operation by SOS Intermediate Section No. 2 from Bongaigaon to Chabua. The LOC was ill-prepared to take on wartime traffic. Part of the broad-gauge line and most of the meter-gauge line were single tracked. The latter was a bottleneck; there were no bridges across the Brahmaputra; the steep gradient at the eastern end of the line made travel slow and hazardous; and monsoons annually disrupted service by washing out tracks and damaging rail bridges across smaller rivers. Also, theBengal and Assam Railroad was called upon to handle increasing traffic. Like the railways, the inland waterway lines were disrupted during the monsoons. At the start of the war, the Assam LOC carried only about 1,000 to 1,500 tons daily. To increase its capacity, in order to support military activities in northeast India, military movement control was gradually introduced. By October 1942, the capacity for military traffic had been increased to 2,800 tons a day, but this was inadequate to cope with the supplies being poured into the LOC. The British then planned in 1943 to construct double tracks, sidings, and a bridge over the Brahmaputra; but few of these projects were completed during the year. As a result, the port of Calcutta became congested. Supplies to Assam took up to 55 days for delivery; and it was not uncommon for shipments to be held more than 30 days on river barges as the year ended. This was of vital importance to the military which was then engaged in expanding construction and airlift operations in Assam, and was about to launch a campaign in north Burma. American officials pressed the British to militarize transport on the LOC. In a compromise, they agreed to a system of semi-military control with U.S. participation in a control board. So, then, a LOC panel implemented allotments and controlled day by day operations. The British made improvements at important rail and river trans-shipment points. Also, they constructed a four-inch pipeline on the Chandranathpur-Manipur Road sector. That line was later extended from Chittogong to Tinsukia. These new pipelines eased the burden on the hard pressed railways, and greatly increased the capacity of the LOC. Playing a vital part in the LOC's development was the transfer to U.S. control of the meter-gauge line from Katihar to Ledo, a portion of the LOC long considered to be a major obstacle to rapid movement of supplies to Assam. What had been a major transportation problem in March '44, was being licked in May. CBI SOS reported to the War Department on July 15 that the target for LOC tonnage set for January '46 had been exceeded, except for the movement of petroleum products which were then unavailable in sufficient quantities. When the India-Burma Theater was createdin October 1944 (and a separate China Theater), the Assam LOC was no longer a problem for the movement of supplies to the forward areas. U.S. and Britishshipments had increased from 112,500 tons in March 1944 to 209,748 tons in October. Some problems remained, however, such as handling of heavy lifts at trans-shipment points, and in meeting the ever-increasing demand forpetroleum products for the East Bengal and Assam airfields. Traffic mounted steadily into the spring of 1945. In March 1945, a record 274,121 tons of U.S. and British military supplies were shipped by river, rail, and by pipeline. The largest new addition to the LOC came in March with the completion of the six-inch pipeline from Chittogong to Tinsukia; this augmented deliveries by the Calcutta-Tinsukia pipeline and the rail and river carriers. Together they provided petroleum products needed for Hump deliveries; fueled the U.S. pipelines extending from Tinsukia into Burma toward China; and supplied fuel for the vehicles on the Burma Road. When campaigns in Burma ended, demand for supplies lessened; but this was partially offset by the need for deliveries to China, especially for fuel needed for air, truck and pipeline operations. This amounted to 135,796 tons in August 1945. Upon termination of hostilities, traffic dwindled; the joint U.S.-British panel was discontinued, and by the middle of October 1945, U.S. railway troops were removed. THE MILITARY RAILWAY SERVICE IN INDIA-BURMA In December 1944, the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia Command (SEAC), Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, wrote of the MRS: "In the first few months of my appointment to this command, the inadequacy of the Assam LOC to meet in full the requirements of the forces in the forward area and of the airlift over the Hump into China was a major obstacle hindering the full deployment of U.S.strength against the enemy. "Already the capacity of the Assam LOC. as a whole, has been developed to a stage where planned development is beingreached months ahead of schedule. Through the hard work and resourcefulness of your railway battalions and those associated with them, the volume of traffic handled has mounted steadily until the LOC is functioning with a substantial margin over essential requirements which will enable unforeseen contingencies to be met." The use of U.S. railway troops on the bottleneck meter-gauge rail portion of the Assam LOC was approved by the Government of India in February 1944. The MRS would operate 804 miles of the railway branch lines from Dhubri and from Neamati; and from Furkating to Jorhat; and also on the short Dibru-Sadiya line to Ledo. In December 1943, MRS Headquarters was set up at Gauhati under Col. J. A. Appleton (later by Col. Yount). In January 1944, a railway grand division (five railway operating battalions, and a railway shop battalion) arrived. In March 1944, the MRS took over the railroad; its 4,200 troops were super-imposed on the existing civilian staff of 13,000. The 705th Railway Grand Division was stationed at the midway point at Gauhati; the 758th Railway Shop Battalionat Saidpur with a detachment at Dibrugarh. To relieve the bottleneck, the MRS forced the loading of the maximum number of wagons (up to 100) at Parbatipar. This greatly expedited the movements. As a result, the meter-gauge railway was soon hauling more tonnage than the 233 mile broad-gauge system running north of Calcutta. As critical points of the MRS line were brought under control, Parbatipur (the trans-shipment point between the broad and the meter-gauge lines) controlled by the British became the bottleneck. So, in October 1944 the MRS, through the 28th Traffic Regulating Group took over all trans-shipment activities at Parbatipur. In the path of the railroad were some 30 rivers and tributaries that were a constant threat during the monsoons. The MRS took flood control measures by reinforcing bridges, cutting diversionary channels for the waterways, and other such measures. The 758th Railway Shop Battalion improved the repair and maintenance function. Before they took over, much of the existing rolling stock had deteriorated. With critical short spare parts obtained from the U.S., they no longer had to cannibalize existing equipment. In 1944, the unit repaired over 47,000 cars and converted about 188 boxcars into trooptrains, refrigerator cars and low side gondolas. From the time the MRS took over, records for tonnage hauled continued to be broken, and the number of troops carried by rail reached a peak of 92,000 (US and Allied) moving east through Pandu, and later moved 133,000 returning. RAIL OPERATIONS IN BURMA The MRS also provided personnel for an unusual rail operation in support of Allied troops driving down the rail corridor from Myitkyina. The 61st Composite Co. of 160 men, began operating the captured portion of the railway.Only 376, out of 571, rail wagons were unscathed from Allied bombings, and most of the tracks were not serviceable. The 61st, set up shops, mounted armed jeeps on flanged wheels, placing them at each end of the trains for motive power and protection. These were used to move supplies and troops mainly in support of the British 36th Division.Engineer troops had already begun to repair tracks and bridges over the 38 miles of track from Myitkyina to Mogaung. Despite nearby enemy activity, they moved 15,615 troops and 1883 tons of supplies in August 1944. During the ensuing months, jeeps were replaced by locomotives and other repairs were made. By the end of January 1945, the rail line extended 128 miles to Mawlu. They also supplied the 10th Air Force Base at Sahmaw. After moving 40,271 passengers, and 73,312 tons of freight in January 1945, traffic declined. In March 1945, the unit returned to Assam. In August, the 61st became the first unit from the Theater to return to the U.S. for demobilization. AMERICAN BARGE LINES IN INDIA In May 1943, it was proposed to establish an American Barge Line (ABL) on the Irrawaddy River, between Rangoon and Bhamo. In Washington, preparations were made to procure the necessary equipment and personnel.Later, the Combined Chiefs of Staff decided to use the ABL on the Brahmaputra River. The requirements were for 400 barges. 180 Chrysler sea mules, and 114 wooden patrol boats. Personnel needs were for a headquarters unit,four harbor craft companies, a port battalion, and an engineer battalion. Later it was found that the equipment procured was not suited for the Brahmaputra River so the ABL was to be used for harbor duty and short river hauls.Meanwhile, the ABL Headquarters was established near Calcutta in November of 1943. Equipment began arriving early in 1944, and assembly was started by the engineer troops, assisted by native labor. The 326th and 327th TC Harbor Craft Companies arrived in April, and they began operations to the Calcutta area. By mid 1944 they were hauling approximately 5.000 tons a month from shipside to depots and airfields up river. A second important activity (in August 1944) was to support two U.S. airfields at Tezgaon and Kurmitola, near Dacca in East Bengal. They hauled petroleum products from Goalunab to Dacca, a round trip of about 200 miles. They ALSO hauled dry cargo for the Air Force from Khulma to Dacca. ABL operations around the port of Calcutta continued to expand; they moved about 20.000 tons a month, and also provided general passenger service. To support Hump operations, and lighten the load on rail and pipelines, the ABL began to deliver almost four million gallons of fuel monthly from Goalundo to Dacca; as well as over 10.000 tons of dry cargo from Khulma to Dacca. In August 1945, the ABL operation closed and the remaining craft and personnel were used at Calcutta to assist in the evacuation of troops and supplies. MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ON THE STILWELL ROAD The task of restoring land communications with China was started in December 1942. Pending the recapture of the Line of Communication (LOC) from Rangoon northward, it was decided to follow a route from Ledo through the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys in North Burma to a junction with the Burma Road. After the U.S. assumed responsibility for constructionof the road, American troops took over and continued work begun by the British. The mountainous jungle of the Patkai Hills between Ledo and Shingbwiyang, at the foot of the Hukawng Valley, presented a formidable barrier. After trucks went as far as the road would permit, native porters took over through narrow trails and mud. This precluded the use of elephants and pack animals. Supplies were air-dropped by the spring of 1943.Construction went slowly and was virtually halted during the monsoons in May. In October 1943, Col. Lewis A. Pick (later Major Gen.) was appointed commander of Base Section No. 3 (later called Advanced Section No. 3), and took command ofall SOS forces on the Ledo Road. When the monsoons ended, rapid progress was made. By the end of 1943, bulldozers had reached Shingbwiyang at the 103 mile mark, and in late December, the first convoy arrived there from Ledo. As Allied forces struck deeper into North Burma, the road was pushed forward behind them. Plans when the road was completed, called for movement of about 85,250 tons a month to Kunming, and 16.500 tons for use in Burma. Assuming that the Allies would recapture North Burma down to Bhamo by February 1944, and that the rest of Burma would be retaken before the monsoon in May, plans called for the development of the LOC, first from India through North Burma, and then northward from Rangoon. It called for water shipments to Calcutta and Rangoon, the latter to receive the bulk of shipments for China; onward movement from Calcutta by rail and river to Ledo, and fromRangoon by barge on the Irrawaddy River to Bhamo; and finally deliveries to Kunming by truck and pipeline from Bhamoand Ledo. This called for the use of 18,000 drivers. 12,000 ¾-ton truck-tractors, and 10,000 5-ton semi-trailers; all to arrive between January and June of 1944. The Combined Chiefs of Staff later decided that combat operations in the dry season of '43-'44 would be limited to North Burma. As a result, all attention was then given to the Ledo-Burma Road. Thus, the combination of the 5-ton 4x2 truck-tractor and the 5-ton semi-trailer was selected for the planned operation.and the War Department undertook procurement action of 8,000 of these units in September 1944. At the Allied Quadrant conference, new plans were made based on an input of 96,000 tons at Ledo, of which 65,000 tons would go to Kunming. The result was in February, a block system of operations requiring 8,270 truck-trailers and 92,800 service troops. The plan called for bitumen surfacing of two lanes. Later plans cut this down to a monthly input Until the fall of 1944, plans for the Ledo-Burma Road operations were based on two-way traffic from Ledo to Kunming and the use of truck-trailers. But then there was the possibility that such vehicles would be unable to operate overthe mountainous Ledo-Shingbwiyang section. This then gave rise to proposals for the partial use of 2½-ton 6x6 trucks. In the meantime, the War Department, in order to make more resources available for the Pacific, cut back constructionplans for the Ledo Road. In August 1944, CBI was notified that a two-track gravel all-weather road would be completed from Ledo to Myitkyina; also that the existing trail from Myitkyina would be improved with the minimum construction required to complete projected pipelines into China and to deliver vehicles and artillery, (i.e.. two-way traffic to Myitkyina but only one-way traffic to Kunming). As a result, scheduled production of truck-tractors and semi-trailerswas cut back to 5,050 and 4,210 respectively. When the China Theater was created in October 1944, the Ledo Road was then operational only as far as Warazup, 190 miles from Ledo, and was being pushed rapidly toward Myitkyina. To provide drivers, a training school was opened at Ramgarh with 500 Chinese students. Other Chinese were flown in from China and a number of Chinese tank battalions at Ramgarh were converted to truck units. Tests in December 1944 confirmed that truck-trailers were unsuitable over the mountainous Ledo-Shingbwiyang run, so the India-Burma Theater requested that 2½-ton trucks be substituted. Further changes were then made by the WarDepartment which provided that road operations would be limited to one-way deliveries of vehicles; also that the six-inchpipeline originally planned for extension into China would be suspended at Myitkyina. leaving only a four-inch line to be completed to Kunming: also that Hump deliveries would be greatly increased. By January 12, 1945, the Ledo Road had been joined with the old Burma Road, and the Japanese were being cleared from the route. So, restoration of land communications with China was at hand.Accompanied by the media, engineers, military police, and Chinese drivers and convoy guards, American drivers under Col. Dewitt T. Mullett, the convoy commander, pushed off for China with the first convoy. After being delayed byfighting enroute, the vehicles rolled into Kunming on February 4. Three days earlier, the dispatch of regular convoys had begun. The opening of the Ledo-Burma Road, soon to be redesignated the Stilwell Road. forged the last link in the chain of land communications between Calcutta and Kunming. To feed this supply line, vehicles were moved by rail from Calcutta to Siliguri, Bongalgaon, or direct to Ledo. Under the direction of SOS Intermediate Section No. 2, vehicles were convoyed from Siliguri or Bongaigaon to Chabua for delivery to Ledo and onward shipment to China. Thus, the highway LOC actually extended 1.759 miles from Siliguri to Kunming. The Stilwell Road itself was 1,079 miles long. From Ledo to Myitkyina the road was of two-way, all weather, gravel construction, the first 103 miles traversing the Patkai Hills before extending across the flat jungle country of theHukawng and Mogaung Valleys to Myitkyina. From Myitkyina to Bhamo, a one-lane route continues to join the Burma Road at Mong Yu, 470 miles from Ledo. From Mong Yu to Kunming, the road was two-lane, all-weather, and hard surfaced over most of the distance, but rough with long grades. Anxious to begin operations as soon as possible, SOS Headquarters on January 21, ordered Advance Section No. 3to start the one-way movement of vehicles to China immediately; but Advance Section No. 3 was not yet organized to set up the necessary convoy details. The only vehicles available in the Ledo area were trucks in poor repair condition. As a result, ordnance personnel worked through the night to recondition the vehicles. Drivers were provided bythe Chinese Army in India, and personnel from a Quartermaster truck company in Burma were diverted to accompany convoys as far as Myitkyina. On the following morning, 50 vehicles and 100 drivers made the start. Early in 1945, a Motor Transportation Service (MTS) was established under Col. Charles C. Davis, operating under Advance Section No. 3. THE BURMA HAUL Burma convoy operations had been established long before the Stilwell Road was opened to China. Since late 1943,Quartermaster truck companies had the job of carrying personnel and supplies from Ledo to Shingbwiyang and beyond as road construction moved forward. Although the men and animals in combat were dependent on air-drop, the forward air supply bases at Shingbwiyang and Warazup were themselves supplied by road. Throughout the year, the truck drivers moved supplies from Ledo to Burma bases, negotiating steep grades and hairpin turns, traveling through dust and mud. In the rainy season it was not unusual to see bulldozers dragging vehicles out of flooded-out muddy roads.As the monsoons neared its end, all available drivers and vehicles were assigned to Burma convoy operations. In the latter part of the month about 550 tons a day were being carried. By January 1945, 46 truck companies were engaged in the Burma Haul. At this time, 13 other companies were assigned to intrabase and depot operations, and 13 additional units were enroute to the CBI. In early 1945, all shipments to Burma were made by 2½-ton trucks, which returned to Ledo; beginning in February, five-ton truck-tractors and semi-trailers were substituted over the rest of the Burma run. By May, there were 38 Quartermaster truck companies assigned to the Burma Haul. For a time, American trucking units were supplemented by convoys driven by Chinese military units. The Chinese never proved satisfactory because American liaison officers assigned to the units had no command function. This problem ended with the movement of Chinese troops out of Burma. CHINA CONVOY OPERATIONS The first month of China convoy operations was one of constant crisis, with a lack of drivers being the most serious problem. After the first regular convoy on February 1, 1945, efforts were made to use Chinese drivers with American officers in charge, but the experiment proved a dismal failure. The training at Ramgarh was inadequate, and on February 24, Gen. Pick reported that he had 1,400 Chinese graduate drivers at Ledo, none of which were prepared for convoy duty. Additional training was then given by Advance Section No. 3, but the trainees never proved entirely satisfactory, so their use came to an end in June 1945. To keep the vehicles moving to China, several converted tank battalion, with experienced drivers, were used, 150 of them were returned by air for additional hauls after delivering vehicles. Other drivers were obtained from the 330th Engineer Regiment, and from Chinese completing advanced training to Ledo. In addition, American units moving to China were assigned vehicles consigned to China. With the foregoing, 22 convoys (of 1,333 vehicles and 609 trailers, carrying 1,111 tons of cargo) made it to Kunming in February 1945. In the months that followed, the MTS used volunteers from a11 over the India-Burma Theater, Chinese and American casuals and units moving to China, some Chinese trainees, and such Quartermaster truck drivers as could be spared from the Burma operations. Volunteers and other MTS drivers were returned by air over the Hump. In this manner MTS was able to increase deliveries of 2,342 vehicles, 1,185 trailers and 4,198 tons of cargo in April; but no firm solution to the driver problem had yet been found. ' Relief came in May and June with the end of the combat operations in Central Burma, and the assignment of Indian civilian drivers. This permitted the release of Quartermaster truck companies for China convoy duty. and in June enabledthe MTS to discontinue the use of Chinese drivers. On July 17. 1945, a total of 26 truck companies were being used for China convoy duty. Also, the only other vehicles consigned to China were those added to U.S. Army units moving to China. A China Traffic Branch was set up to control all convoys from Ledo to Kunming. Nine stations in all, were there to provide maintenance, messing, communications, and overnight quarters. Also. a Border Guard Station at Wanting and later at Mong Yu was established, manned by MPs to see that only authorized personnel passed through. Problems crept up, such as poor convoy discipline and laxity in maintenance of vehicles by drivers. This was correctedby vigorous MP control and assignment of tools and native labor at these control stations. By May 1945, operations were in high gear; 78 convoys delivered 4,682 trucks, 1,103 trailers, and 8,435 tons of cargo. With exclusive use of American drivers in June, the average time from Ledo to Kunming (originally 18 days) was reduced to 12-14 days. THE CLOSE OF STILWELL ROAD OPERATIONS With war's end. most operations were terminated. In September 1945, only 4,112 tons were delivered to bases to Burma. On August 27, the final delivery was made to Kunming, and it consisted of 4,000 trucks, and 8,000 tons of cargo. Vehicle dispatches ended on September 23, except for a few special movements. By November 1, the Stilwell Road was officially closed; six days later the MTS was inactivated. From February 1 - October 8, 1945, a total of 25,783 vehicles and 6,539 trailers were delivered to China by MTS drivers and by American and Chinese units, in addition to 38,062 tons of cargo. Stilwell Road deliveries were overshadowed by the Hump airlift, and after the pipeline to Kunming was operating,its deliveries exceeded the net cargo over the road. Considering the problems of drivers, road and climatic conditions. the record of motor transport on the Stilwell Road is impressive. The number of vehicles delivered greatly relieved the critical transportation situation in China. Cargo delivered to Burma helped make the Burma campaigns. and road and pipeline construction possible. Within theconfines of Its mission, and the resources available, the Stilwell Road made a valuable contribution to the war in Southeast Asia and materially Improved the intra-China transportation system. U.S. ARMY TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA Delivery of supplies over the Hump to airfields in Yunnan was a job half done. From Kunming, they had to be hauled forward by rail, road. and water, over the Eastern Line of Communication (ELOC), a complex and difficult route. Supplies were moved from Kunming to Kulsing by meter-gauge railroad. From Kutsing (later Chanyl when that railroad was extended), the Southwest Highway Transport Administration (SWHTA), a quasi-governmental agency, or other carriers, trucked cargo eastward to Kweiyang, and thence north to Chungking, or south to Tushan. A standard-gaugerailroad delivered supplies from Tushan to Yuchow and/or Kweilin, and from those bases movement was by rail, truck, river craft or coolie. Before 1944, the U.S. relied almost completely on Chinese agencies for transportation. When the Services of Supply, U.S. Army, was established in Kunming in July 1942, few men, and practically no equipment, were available for this function. With the closing of the Burma Road, and with scarce Hump capacity, most early SOS activity was devoted to receiving air freight and expediting forward movement of supplies. As SOS activities were extended forward, officers were stationed at important trans-shipment points to expedite movement. When SOS opened a branch office at Hengyang in May 1942, a few vehicles were purchased locally and operated bySOS personnel to carry bombs and ammunition to newly-constructed 14th Air Force bases. Later depots were established atYunnanyi, Chanyi, and Chungking. The ELOC assumed importance in late 1943. Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault began to expand his operations, and by the end of October, had seven fighter squadrons and two medium bomber squadrons, which were dependent on this ELOC and limited air transport, for support. The transportation situation in China had long been difficult; pre-war vehicles had to use primitive roads, with no replacements, and few spare parts. By the end of 1943, trucks were being rapidly reduced to junk, bringing motor transport almost to complete collapse. The main bottleneck on the ELOC was the 400-mile highway linking the railheads of Kutsing and Tushan. This road was rugged, poorly maintained, and full of steep grades. It included the often photographed 21 hairpin road (see photo). toward the end of 1943, Chennault exerted strong pressure to improve the ELOC to allow for expanded air operations in East China. Early in 1944, Col. Sheahan was appointed SOS Transportation officer at Advance Section No. 1, to improve the critical shortcoming. He found disheartening conditions. The SWHTA,the principal carrier, owned 1,196 vehicles but only 183 were operable, and most trucks were using substitute fuels. Preventive maintenance was practically non-existent and overhaul work was primitive. To provide better support to the 14th Air Force, Sheahan in February proposed the movement of 8,000 tons of cargo per month from Kutsing to Tushan. That goal required rehabilitation of 1500 Chinese trucks, and the use of some American motor transport. The plan involved shipment from India (over the Hump) of 700 trucks, and 2000 tons of spare parts. Also, he needed several Quartermaster Truck Companies and an Ordnance Heavy Automotive Maintenance Company (Project TIGAR). The plan also included extension by the Chinese of the rail lines from Kutsing to Chanyi, and from Tushan to Tuyan. When this plan In addition, U.S. officers were assigned to Chanyi, Annan, Kweiyang, and Tushan to coordinate shipments. By the end ofAugust, Sheahan's organization had 27 officers at Kunming and key points along the ELOC. By the end of May, the 857th Heavy Automotive Ordnance Co. set up shop at Chanyi. The 3842nd Quartermaster Truck Company arrived in Chanyi on June 1st, and three days later with 93 trucks, began to run convoys to the Tuyan railhead. The first round trip took seven days, in contrast with the 2½ weeks previously required by Chinese trucks. By the end of the month, U.S. Army vehicles were carrying 17% of the tonnage on this part of the route. All the above effort brought a substantial increase in ELOC traffic. During June, 3,379 tons of cargo went from Chanyi for the 14th Air Force. This, however, was less than half the needs of Chennault, who along with the Chinese armies, was faced with the task of containing a major Japanese offensive. Despite many obstacles, the ELOC's output increased during the summer of 1944, and in August the arrival of two additional Quartermaster truck companies, and additional trucks, helped considerably. Operations reached their peak in September and tonnage for the first time approximated what Chennault needed. The improvements, however, came too late, for by then the enemy had overtaken the east China air bases, and were threatening those in central and south China. In April 1944, the Japanese had driven south of the Yellow River. In their continuing offensive, they took Heng-yang in August, and then moved on to Kweilin, which had to be evacuated by the end of October. It appeared also thatLiuchow and Nanning would follow. As a result, alternate routes had to be set up, but none survived except that from Kweiyang to Chihchiang, which alone among the eastern airfields withstood the enemy's offensive. In these actions,transportation personnel helped evacuate refugees and troops from eastern bases. Disruption of traffic on the ELOC became increasingly severe during the fall of 1944. In August, traffic forward of Kweiyang and Chihchiang was at a standstill except between Liuchow and Nanning. Roads were clogged with refugees, and truck service on the Chanyi-Tushan highway was over-taxed because of Chinese troop movements. As a result, eastboundshipments from Chanyi dropped to 2,772 tons in October, and in November only 1,760 tons were moved. During the first 20 days of December, transport was practically nil, with only 189 tons moving eastward from Chanyi. By the end of 1944,the ELOC extended only as far as Tushan and Chihchiang, just half the length before the Japanese offensive began, yet the tactical situation needed more supply for operations in the north. In October, two of the three Quartermastertruck companies were diverted from the ELOC to support B-29 bases in the Chengtu area and other northern fields. The critical tactical situation in the latter part of 1944 necessitated a radical reorganization of the motor transport function. Chinese carriers were pulled off of ELOC hauling for the 14th Air Force and used to evacuate and move Chinese troops into defensive positions. This required the diversion of three U.S. truck units along with their Chinese drivers. Operating from Kweiyang, the 3731st Quartermaster Truck Company helped in the evacuation of Liuchow and Nanning, and also hauled supplies to the besieged air base at Chihchiang. The other two units, after being diverted to the support of the northern airfields, were returned to the ELOC for the movement and supply of Chinese troops. Only such vehicles that could be spared were used to supply the U.S. Air Force, so they had to move most of their supplies by air from Kunming and Chanyi to their remaining airfields. The transportation picture continued bleak in early 1945. Chinese civilian carriers were failing to meet their commitments by 50-75%, and American truck units showed no marked improvement. The arrival in February 1945 of the first vehicles over the Stilwell Road offered some improvement, but the first large addition to ELOC operations came with the arrival of the LUX Convoy in March. This was the 517th Quartermaster Group which included seven truck companies, and an Ordnance Medium Automotive Maintenance Company. That unit brought in 600 2½-ton trucks and 83 truck-trailers. The LUX Convoy came from the Persian Gulf Command. Initially they were to come by land, 5,534 miles by rail and highway from Iran to Chungking, via Soviet Turkistan. The USSR at first was unwilling to permit this move, but later in September 1944 they finally agreed, but news of disturbances in Sinkiang Province caused the move to be delayed. Finally, the unit was shipped by water to India for movement over the Suiwen Koaa, arriving in Kunming in March 1945. Later in March, the 517th Group was reinforced by other Quartermaster Truck Companies. A block system was started over the 327-mile route from Chanyi to Kweiyang. They also carried supplies from Chungking and from Nekiang to Kweiyang. alsofrom Kweiyang to Chihchiang. The addition above, produced Immediate results. In March, they hauled 12,506 tons; almost double that of February. With additional reinforcements, the 517th by the end of June had 436 U.S. and 2,367 Chinese drivers operating 1,318trucks. Then in May, two Chinese tank battalions, which were converted into truck units in India, joined the ELOC. These were under the command of the Chinese SOS. but under operational control by the American SOS. By May 1945, U.S.controlled vehicles were hauling more than five times that of Chinese carriers. As the enemy began withdrawing from south and central China, the LOC was lengthened to the south and east. From Maythrough July, the job was to haul Chinese troops and supplies to combat areas in southwest Kwangsi and west Hunan Province to support actions that resulted in the liberation of Nanning and Liuchow and the opening of a drive from Chihchtang toward Heng-yang. During the above period, the 517th Quartermaster Group handled increasing traffic from Chanyi to Kwetyang and Chungking;and they also set up a route from Chanyi to the new Luhsien Air Base. Peak traffic was attained in June 1945, when U.S. controlled carriers moved 58,156 tons. As the end of hostilities approached in August, 546 American, 2,511 Chinese civilians, and 7,010 Chinese military drivers were operating under U.S. control. In the last months of the war, SOS Base Sections took over complete control of motor transport. The LOC from Chanyi to Chihchiang, Liuchow and points east became the responsibility of Base Section No. 3 at Kweiyang; support for the Ft. Bayard operation was assigned to Base Section No. 2 at Nannlng. Inland water transport had been the principal way to move people and supplies, but since the Japanese seized areas near the great rivers of China, American use of that mode was minor. Some tributaries of the Yangtze were used for shipments to the Chengtu and Chungking area. Also, in May 1945, the Yuan River between Chanyan and Chihchiang was used with about 950 boats. When Nanning was secured in June 1945, the Hsiyang River was used with enough craft to move 3,000 tons a month. Following the Japanese surrender in August 1945, the task was to assist the Chinese in disarming the Japanese and reoccupying liberated territory. Motor transport in West China was then used to haul supplies to Chihchiang whereChinese forces were being airlifted to Nanning and Liuchow. By mid-August, all north-south traffic on the LOC, with a few exceptions, had been halted and vehicles were placed on the run from Chanyi to Chihchiang to support Chinese forces. By November 1945, the Stilwell Road, pipeline and Humpoperations were terminated, and from then on all supplies and personnel were being brought in through Shanghai. By the end of the year, a total of 47 vessels and 156,989 tons of cargo had arrived at that port operated by the U.S. Army.

to use American troops and equipment to ease the bottleneck and develop the Assam Line of Communications (LOC). This task was described by logisticians in Washington as the most fascinating and complex problems in the worldconsisting of rail, water, rail-water, water-rail and limited highway routes.

Debarkation was operating efficiently.

"Sea Mules" at work on the barge line from Calcutta

"Sea Mules" at work on the barge line from Calcutta

of 57.000 tons of which 45.000 would go to Kunming, and included 36,727 service troops (drivers, maintenance and support).By April 1944, approximately 300 cargo vehicles were being dispatched dally over the Ledo Road.

came to fruition, shipments eastward from Chanyl increased from 1931 tons in February 1944 to 3068 tons in May, even before the U.S. Army trucks began operations. Truck convoy operates on the famous 21 curves at Annan between Chanyi and Kweiyang, China.Drivers often battled with bandits who would board the slow moving vehicles to pilfer supplies.

Truck convoy operates on the famous 21 curves at Annan between Chanyi and Kweiyang, China.Drivers often battled with bandits who would board the slow moving vehicles to pilfer supplies.

China-Burma-India Theater Lines of Communication

Transportation in the CBI Theater of World War II

by Lt. Col. Joseph B. Shupe, USA (ret.)

TOP OF PAGE PRINT THIS PAGE COMMENTS

OVERVIEW INDIAN PORTS THE ASSAM LOC STILWELL ROAD TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA

Adapted for the Internet by Carl Warren Weidenburner

Copyright © 2006. All rights reserved.