China-Burma-India Theater ONE SOLDIER’S STORY |

|

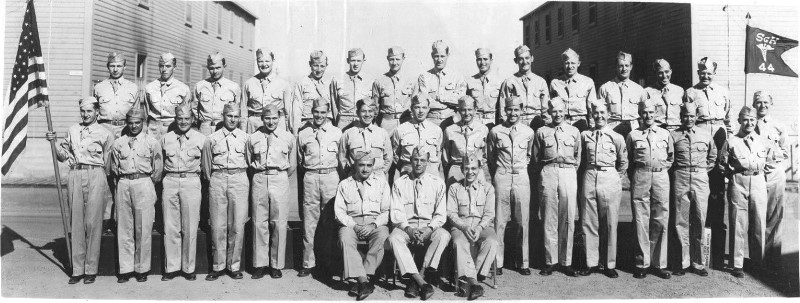

Members of the 44th Portable Surgical Hospital at Camp White, Oregon

|

There is a greater story that begins this of the 44th PSH in CBI. It is the story of the HMT Rohna, a British ship carrying members of the 44th PSH to India and the China-Burma-India Theater of World War II. On November 26, 1943, while en route the Rohna's convoy was attacked off the coast of Algeria by German Luftwaffe Heinkel He-177A heavy bombers launching Henschel Hs-293 radio-guided, rocket-boosted, glide bombs (the first guided missiles). The Rohna was the only ship hit, eventually sinking and taking the lives of 1,015 U.S. soldiers. It remains the largest loss of U.S. troops at sea due to enemy action in a single incident in U.S. history. An additional 35 U.S. troops later died of wounds sustained in the attack.

The survivors from the 44th Portable Surgical Hospital included twenty enlisted men and three officers. Six of the 44th PSH surviving enlisted men and two officers were taken to a nearby hospital. Thirteen enlisted men from the 44th PSH were classified as missing in action.

The loss of life is only part of the tragedy of the sinking of the Rohna. The radio-guided bomb/missile that struck HMT Rohna was one of the first to be used against the Allied Forces. The significance and secrecy of the weapon was such that the U.S. War Department classified the attack top secret, ordering all survivors of the sinking to remain silent. Similarly, the War Office and British military classified their documentation surrounding the sinking. Most survivors did not disclose anything about the horrifying event they lived through. The families of those who were killed in the attack were never told what happened to their loved ones. There were no War Department phone calls, letters, or visits made providing information that would bring closure to the families. Most of the bodies of the soldiers were never recovered. In most cases, there were no funeral services or burials for the forgotten soldiers. Six months after the attack, the Gold Star families back home received one short paragraph confirming the death of their loved one in a telegram that also stated that there was no information available. The secrecy continued for decades.

More information about the HMT Rohna at this link: ROHNA SURVIVORS MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION

The 44th Portable Surgical Hospital was activated from the 82nd General Hospital at Camp White, Oregon on July 15, 1943. On September 9, 1943 the 44th departed Camp White and traveled via rail to Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, arriving on September 13, 1943. On October 2nd, the 44th boarded a Liberty Ship, the SS Betty Zane and departed Hampton Roads, Virginia headed for Oran, Algeria in North Africa.

The Betty Zane and the 44th arrived on October 22, 1943 in Oran, Algeria. On October 23 the Unit disembarked the ship and was placed in a staging area, Camp #2, Area 18. Military training was taken up and continued until November 1st at which time the Unit was moved from the staging area to the 23rd Station Hospital. The officers and unit personnel took up their assigned duties in their respective departments. Training ensued relative to treatment of battle casualties, surgery, sanitation, and Malaria control and treatment. While there the men were issued passes to go into Oran and the surrounding towns. On November 25, 1943 they headed for Bombay, India through the Suez Canal. The attack on the Rohna occurred the next day, November 26, 1943.

Those rescued by various ships were taken to North Africa and then eventually to Tunisia. On January 8, 1944 the 44th PSH survivors resumed their journey. After sailing from North Africa and through the Suez Canal, into the Red Sea, into the Gulf of Aden, and lastly into the Arabian Sea, they arrived at the city of Aden, Arabia on January 26th, 1944. Once in the Arabian Sea they sailed to Bombay, India. The trip to Bombay was uneventful, and on January 30th the unit reached the port of Bombay and the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater, four months after departing the U.S. at Hampton Roads, Virginia.

On February 1st the Unit was issued passes for a brief sightseeing tour of the city of Bombay. On that same day the 44th PSH Unit was issued orders to depart the city. They left Bombay by train to a point about a hundred miles from the city and arrived at a British transit camp at Deolali, India. After three days of rest and reorganization of personal equipment, they boarded a train bound for Camp Kanchrapara, a station that was 45 miles from Calcutta, India. On February 9th they reached a staging area near Kanchrapara. Here the organization faced issues and problems with re-establishing proper equipment for the Unit. The Unit's equipment, medical supplies, and properties were lost in the sinking of the Rohna.

On March 1st the reorganization of the Unit was completed and the medical supplies shipped via the Pacific Ocean arrived. Once everything was loaded the Unit was ordered to proceed to Chabua, a town in the Dibrugarh district in the state of Assam, India. It was here that the Unit waited for transportation to arrive, which would transport them over "The Hump" to Kunming, China. The trip to Chabua was made via train and river boat, arriving there on March 8th. Once there the 44th PSH spent several days packing and marking the Unit's equipment for air transport to China. Upon completing packing, equipment and supplies were flown along with the Units Commanding Officer to Kunming, China. During the reorganization and re-supplying of the 44th Portable Surgical Hospital Unit, the war in CBI was in full force.

Allied forces, including the Chinese Military, were battling the Japanese on many fronts. Personnel of the Unit were awaiting transportation to Chabua Staging Area, when orders were given on April 15th to proceed to Moran Air Field, with the purpose of medical support of the 89th Chinese Regiment. This Chinese Regiment was being staged for possible use against the Japanese, who at that time were threatening a break through to the Bengal-Assam Railroad from established positions in the Imphal and Kohima sector. Battles of Imphal and Kohima were fought between March 8, 1944 and July 18, 1944; these were the turning points of one of the most grueling campaigns of the Second World War. The decisive Japanese defeat in northeast India became the springboard for the Army’s subsequent re-conquest of Burma. With all of the Units equipment and supplies already in China, it was necessary to re-supply the 44th Unit again, since they had been reassigned. Cooperation between the officer in command of the 44th and the Supply Officer of the 111th Station accomplished this task. With the aid of the 111th, the 44th PSH was set up for its initial operation at the Moran Air Field on April 16, 1944.

During the next five weeks the 44th PSH acted in a dual capacity of a Clearing Company and a Surgical Hospital. They performed an ambulance service to the 111th Station Hospital, in addition to doing both medical and surgical duties in treating wounded Chinese soldiers.

Since the unit was committed to this assignment in a fixed location, time not spent on treating wounded was spent on training in preparation to being deployed as a portable unit. A satisfactory method for packing of hospital supplies for jungle transport remained a major concern and potential problem. Various types of pack boards were tried-out and tested on vigorous road marches, as well as ones made from bamboo and the use of native Chinese laborers. Supplies were broken down to bare minimum weight, in an effort to determine whether personnel of the hospital could carry enough hospital equipment, plus personal equipment to make the Unit effective as a portable hospital.

Conclusions drawn about this training were that for short marches, such might be feasible only if airdrops of supplies were regular and the terrain was not too difficult. Testing of backpacks was also conducted. The addition of more than 20 pounds of hospital/medical supplies was inadvisable, especially for personnel having to carry a loaded pack that would have to be carried by personnel in the hot weather and harsh terrain. Trial and error resulted in modifications to the Yukon pack board, which afforded a pack that would be the best for transporting the hospital/medical items.

Surgical work at Moran Field was minimal, with the majority being battlefield trauma suffered by the Chinese soldiers. In addition, there were a considerable number hospitalized for fevers of various origins, with Malaria being the chief offender. The Unit’s Officers served as Liaison Officers with the 89th Chinese Regiment in the absence of regular liaison Officers. It was here at Moran Field that the Unit received several new enlisted men as replacements for the men lost in the Rohna sinking. Training of the new enlisted men was conducted in order to get them up to speed on the Unit’s responsibilities and duties.

On May 20th, the 89th Chinese Regiment was flown to Myitkyina. Consequently, the 44th Portable Surgical Hospital was ordered to Ledo, a small town in Tinsukia district, Assam, India, arriving there on May 24th. There they were assigned a Staging Area in preparation for air transport to Burma. The Unit prepared and arranged the equipment for air transportation.

After several days of organizing and preparation, the orders were changed. The Unit was then assigned to the 48th Evacuation Hospital for temporary duty. Here medical and surgical technicians were assigned to their respective duties and had the opportunity to advance their technical training. On June 7th the 44th PSH was ordered to the 73rd Evacuation Hospital and preceded by convoy over the Ledo Road to Shingbwiyang [Shing Bwi Yang/Tawa], Kachin State, Burma. The Unit didn’t do much while here except for enhanced training. The town was located in the China-Burma-India Theater during World War II, and the Ledo Road and an airbase were built there during this period.

Starting on August 15th and completing on August 19th, the Unit personnel and equipment were air transported to Camp Robert W. Landis near Myitkyina, North Burma. Myitkyina is the capital city of Kachin State in Burma, located 1,480 kilometers (920 mi) from Rangoon, and 785 kilometers (488 mi) from Mandalay. At this station the 44th PSH was attached to the 5332nd Brigade (Provisional) MARS Task Force for training purposes preparing for long range penetration tactics. For a three month period, training consisted of rigorous road marches, bivouacs, training lectures and animal transport techniques.

The training area which had been set up about ten miles north of Myitkyina on the west bank of the Irrawaddy began receiving members of the 475th Infantry Regiment. The area was designated Camp Robert W. Landis in honor of the first member of GALAHAD to be killed in action. Unit after unit started moving into Camp Landis as the 5332nd began to put on flesh and assume the likeness of a pair of regimental combat teams. Another battalion of pack artillery, the 613th under Lt. Col. James F. Donovan, the 18th Veterinary Evacuation Hospital, the 44th Portable Surgical Hospital, the 1st Chinese Separate Infantry Regiment, Col. Lin Kuan-hsiang, arrived.

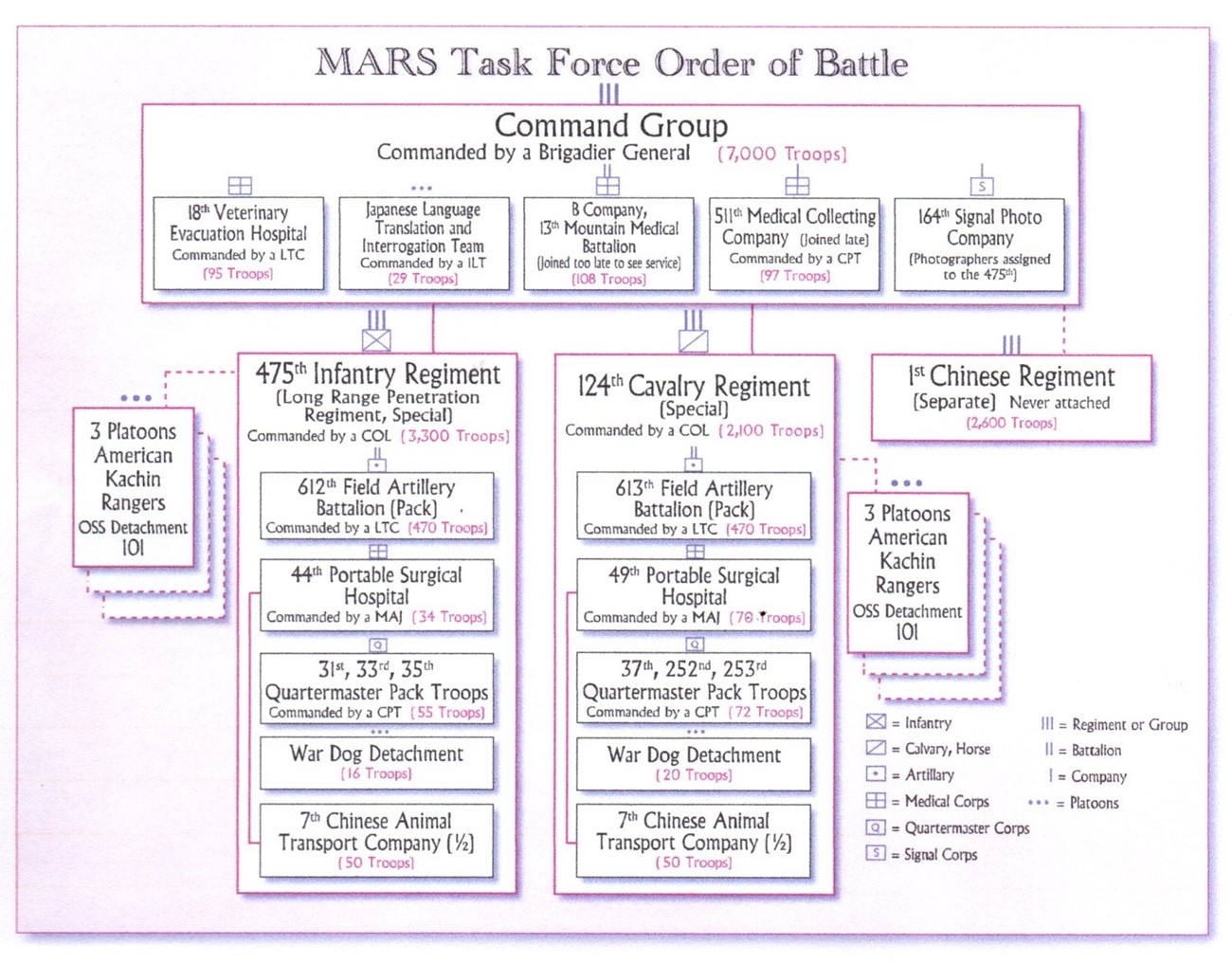

The 5332nd Brigade (Provisional) was activated on 26 July 1944. It soon came to be known as the MARS TASK FORCE. It was designed as a Long Range Penetration Force and training, equipment and organization were all directed toward this end. MARS was able to profit by the experience of Wingate’s Raiders and Merrill’s Marauders in Burma jungle operations. The leaven of veteran jungle fighters was mixed with the freshness of volunteers and the assignment of the 124th Cavalry Regiment. A triangular plan was envisioned and in many ways MARS TASK FORCE was truly a Division, consisting of the 475th Infantry, 124th Cavalry (Sp.) and 1st Chinese Regiment. The Cavalry Regiment had a long history of mounted Cavalry and was converted by MARS to Cavalry dismounted, with the functions and employment of an Infantry Regiment. The 475th Infantry was organized by MARS and given official status as a numbered Infantry Regiment by the War Department. The Brigade itself was organized as a Provisional Unit. Below is the organizational chart of the MARS Task Force Order of Battle.

|

A small detachment of the 44th PSH, consisting of one officer and four enlisted men was sent with a composite force of American and Chinese X-Forces to meet up with a like Y-Force at the China-Burma border. X-Force was the name given to the portion of the National Revolutionary Army’s Chinese Expeditionary Force that retreated from Burma into India in 1942. Y-Force was the South East Asia Command designation given to Chinese National Revolutionary Army forces that re-entered Burma from Yunnan in 1944 as one of the Allies fighting in the Burma Campaign of World War II. It consisted of 175,000 troops divided into 15 divisions. This unit marched 150 miles in 18 days to deliver medical aid to a composite force.

Upon completion of the training program at Camp Robert W. Landis, the 44th PSH was assigned as medical support to the 475th Infantry Regiment. These combined Units departed from Camp Landis on November 16th. The Unit was under new command and moved by foot with animal transport of the equipment. They embarked on their first combat mission nearly one year after the sinking of the Rohna. On November 16th the Unit, moving south, crossed the Irawaddy River via landing barges and arrived at a bivouac area at Waingmaw, Burma. November 18th the Unit left Waingmaw and travelled about 10 miles arriving at Nawlun Sakan. The next day November 19th the Unit moved about 12 miles south to Kazu (Kazuyang). It was decided to not move very far as to not tire out the men. Nine days later, on November 25th the Unit arrived at Tali, Shwegu a village in Shwegu Township in Bhamo District in the Kachin State of north-eastern Burma. This location is about 9 miles north of the Burma Road. The Burma Road was a road linking Burma with southwest China. Its terminals were Lashio, Burma in the south and Kunming, China the capital of Yunnan province, in the north. It was built in 1937-1938 while Burma was a British colony to convey supplies to China during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The portable hospital was set up for potential surgeries. Treatment of patients at this location, however, consisted of treatment of injuries due to accidents related to the march. After five days at this location, the Unit received orders to pack up the portable hospital and move by foot approximately 200 miles to Mo-hlaing, which they reached on December 13th. Mo-hlaing is located on is on northern part of Burma (Sikasso, Shan State), 209 kilometers northwest of Shan State. This location was a remote forest area. Forward elements of the 475th Infantry were already engaged in a battle with the Japanese enemy when the 44th arrived. At this point several casualties were awaiting surgical care. A partially underground surgery center was hurriedly constructed and surgery to patients continued well into the night. Further construction of the portable hospital continued on December 14th, as well as surgical operations on the wounded.

On December 15th at 16:40 hours, the Japanese dropped several artillery shells about 50 feet from the surgery facility, during a critical abdominal surgery on a wounded soldier. Shelling continued that evening and the following morning, injuring two members of the 44th. The Unit treated 24 patients that day. On December 16th The Japanese artillery shelling began once again. This shelling killed a medic. In all they treated six casualties that day.

|

On December 17th, the constant enemy artillery shelling resulted in the Unit completing a more underground surgery facility across a small stream in a better position of defilade (the protection of a position, vehicle, or troops against enemy observation or gunfire). The Unit dug a place for the surgery facility. The shelling subsided and the surgical care of casualties from battle ceased. Medical care continued due to illness and non-battle injuries. The Unit continued to treat wounded and perform surgeries.

On December 18th the 44th treated two soldiers from the 612th Artillery Unit, who was just in the front of the 44th. On the 19th, the battle ceased and things were quiet, but the 44th treated three patients that day. Pat Maccarone reported for duty with the 44th PSH, as did Lt. Sheek from the 44th Field Hospital. On December 20th the 44th set about reinforcing the surgical ward with more logs to provide more protection. The next two days were quiet, but the Unit treated two patients with unspecified injuries or sickness.

On December 23rd and 24th the 44th PSH moved to Tonkwa, Burma which was the scene of a battle the previous week, but no Japanese forces were still in the area. The move was only a mile or so, but the move was tough. The Unit built another underground surgery ward. While at this location the 44th treated patients that were awaiting evacuation of casualties to a larger Army Hospital. During this time the 475th 3rd Battalion was moving into combat action with the Japanese. Christmas Day, December 25th started with firing of mambus and grenades, which gave the Unit a definite scare. A few members shot water buffaloes and butchered them for Christmas dinner. It was the best meal that they had in over a month.

December 26th was fairly quiet and nothing much happened. On December 27th they were told that they would embark on a very tough mission over more rugged mountains. So far the Unit had walked about 200 miles. December 28th, the 44th was still waiting to move. That day they were visited by Brigade Surgeon Major Welker. On December 29th the 44th was still in Tonkwa. Chinese Infantry replacement forces were brought in to relieve the American 475th Infantry.

The next day, on January 1, 1945, the unit started ascending the mountainous region. The first really high mountains, some peaks reaching 7,000 feet above sea level, with a total ascent of about 1700 feet reaching the Shweli River after a 9½ mile march. Shweli River is a river in China and Burma, it forms 26 km of the boundary between Burma and China. On January 2nd the Unit was waiting to cross the river over a huge bamboo bridge. The Unit helped move heavy equipment over the bridge that day. The Unit spent the night on the river bank. They nearly froze as the temperatures had dropped. On January 3rd they started to climb from the river about 2,200 feet in elevation and traveled about 8 miles total distance.

That was the fourth day the Unit was on 3-a-day rations and they were all hungry as hell. It is not known whether they were on C or K rations, as both were used in World War II. K-Rations were lighter than C-Rations, and three meals a day netted only 2,830 calories. Soldiers complained about the taste and lack of calories, and so entrepreneurial leaders often found supplements such as rice, bread and C-Rations. K-Rations were discontinued at the end of World War II. At the end of the day the Unit got and air drop of supplies and rations. About every three days the Unit would receive air drops of supplies and rations. January 4th the Unit continued to climb up and over the mountain top via very narrow trail. Going was very slow and the Unit did not make it to the desired bivouac area, so they slept along the trail.

On January 5, 1945 they arrived in the valley of Mong Wi, where they set up a temporary Basha (an Assamese hut typically made of bamboo and grass) for surgery and medical treatment. January 6th the 44th was still in Mong Wi. Rain began so the Unit put up tarps to stay dry. In addition they set up huts in a rice paddy to house patients. The 44th treated many soldiers for injuries as well as disease at this location. Keep in mind that the 44th was still attached to and supporting the 475th Infantry Regiment. January 7th the 44th moved 2 miles up the valley and set up a Basha for surgery and medical treatment of patients. January 8th saw many sick soldiers from the strenuous march over the mountains.

On January 9th, the Unit was still in the same location. The 475th 2nd Battalion went out on patrol searching for the enemy. The patrol returned with U.S. Servicemen that were involved with a C-47 crash. The C-47 was making air drops when it crashed. One of the men aboard the C-47 died and another had a nervous breakdown. January 10th the Unit was still at this location and had rice, meat and beans for their meal instead of rations. On January 12th the Unit prepared to move.

The unit moved out of the Mong Wi valley on January 13th and found more mountains ahead of them, due to the slow going, the 44th camped on the trail, unable to meet their desire destination. Eventually they arrived at the town of Namama, having traveled only a distance of about 6 miles. January 5th the Unit was waiting for an air drop of supplies. Once the supplies were obtained the 44th moved to the other side of the hill.

On January 16th they left the town of Namama at 07:30. They were told that they would march all day and well into the night. The pace of the march was strenuous until about 15:00 and then it slowed down a bit. At 19:00 they were told that the march would continue through the night. Night came and the march continued, by then the men were very tired and hungry. It was very dark and they could hardly see where they were going. The tied ropes to each other and put their compasses on their back pack so that they could see the illuminated dials of the compass of the man in front of them. Finally, at 03:30 hours the next day, January 17th, they halted the march. The night was very cold, but they did not allow any fires. They had to sleep on the wet ground with no blankets. The reason that they stopped, was because the trail was giving way and several of the mules hauling artillery had fallen over the steep cliff along the trail.

January 17th the Unit moved out at 07:00 hours, and marched about 4 miles, until they halted, to wait for the 475th Infantry (1st Battalion) to secure the village of Namhkum, which the 44th was to occupy. The Unit was halted on a hill just across the valley from the village and watched the Infantry battalion take the village from the Japanese. The 1st Battalion surprised the Japanese. They heard a broadcast of Tokyo Rose, the Japanese claimed that the 1st Battalion had parachuted into the location, but that was not the case. The Japanese didn’t know how it was possible to the U.S. forces to get through the rough mountain terrain. To support the battle the 44th setup the portable hospital about a hundred feet from a unit from the 612th Field Artillery Battalion. The 612th fired most of that night toward the Burma Road and the Japanese troops. It was estimated that the U.S. artillery killed about 300 Japanese.

By the time that the 44th got the portable hospital set up they had wounded waiting for surgery. The 44th was quick to begin surgery on the most severely wounded, and surgery continued the rest of the night and into the next days that followed. They set up in the dark and had to perform belly surgery on a wounded soldier. Everybody was dead tired, but still had to work on treating the wounded.

January 18th some of the 44th PSH constructed a basha for surgery and medical treatment. Meanwhile they all took turns digging foxholes. Surgery was very busy that day and continued into the night until 04:00 the next morning. January 19th the Unit was suppose to dig a new surgery ward in the valley, but all surgery was halted due to Japanese artillery pinning the 44th PSH down. Consequently, no work got done. Once the Japanese artillery ceased the Unit worked until 04:00 the next morning. On January 20th they decided to relocate the surgery to a new location, since the last one was too hot. At the new location the men began to set up the new surgery in this new area. They worked until 03:30 the next morning January 21st.

The 44th moved from their location on a hill near the battle, to a more secure location. About two hours after the 44th relocated the Japanese artillery poured shell into the area, where the 44th just vacated. This proved to be a timely move, as the area was blown to bits. They say that timing is everything, and in this case it certainly was.

The 44th quickly setup the portable hospital in the new location. Wounded kept pouring in on a constant basis and the Unit worked both day and night treating the wounded and performing surgeries. The Japanese kept up the artillery barrage on a steady basis. The men in the Unit referred to the shells as 150 pound flying box cars, and the artillery shells seemed to stop directly over the Unit, with everyone expecting them to fall directly on them. But luckily the shells fell on a hill side just past the 44th. As luck would have it, the 44th was spared, and no one was wounded by the shelling. They had many patients that night, but there was no cover for them. They had to use parachutes as blankets. Also, because of the quick relocation the 44th had no opportunity to dig foxholes for protection.

On January 21st the Unit fixed up the surgery ward and erected a medical hut. The Chinese aided and were very helpful in accomplishing these tasks.

The following day the Japanese continued shelling the hell out of the area. On January 23rd a steady flow of patients arrived at the 44th. This resulted in need for the 44th to build another basha. They didn’t have tarps for the roofs, so they used parachutes. On the January 24th all patients were evacuated by Stinson L-5 aircraft. The Japanese constantly shelled the airstrip, resulting in six planes being destroyed. On January 25th the number of patients decreased, however, the Japanese still where throwing in big stuff.

On January 26th the Japanese where shelling with 150 mm rounds versus the United States using 75 mm rounds. They heard that the U.S. artillery knocked out one of the Japanese guns, but the heavy shelling from the Japanese continued. U.S. artillery continued an assault on the Burma Road, which resulted in the destruction of two Japanese tanks.

On February 3rd the Commanding Officer (CO) of the 475th 2nd Battalion took a direct hit from an incoming round, which blew him to pieces. On that same day General Willeg visited the Unit to congratulate them for outstanding work treating the wounded and sick.

Paul Gartner's diary entry of February 5th, “Looks like we will hit the trail soon. By straight miles we walked 300 miles. That doesn’t count going up and down hills and around trails. From reports we actually walked 400 miles. Colonel McKay, direct from Washington, was here to investigate typhus disease.”

The 44th were very busy both day and night until the fighting ceased on February 8th. During this period of time the 124th Calvary Regiment moved into position and the MARS Task Force was united as a Command Group of combined forces. February 12th it rained all night and the area was very muddy. The Unit set about fixing the place up, as they would undergo an inspection by Lieutenant General Daniel Isom Sultan, 38th Infantry Division VIII Corps Burma-India Theater Inspector General of the U.S. Army. He said everything was ok.

On February 13th, the Unit saw a motion picture “Coney Island.“ This was the first show that they had seen for four months. On the 14th, 15th, and 16th the Unit moved into a rice paddy. The 16th was the coldest night that they had seen so far. On the 17th they had a gun inspection by the Ordnance Unit. On February 18th they had a visit from Supreme Allied Commander of the Southeast Asia Theatre, Admiral Lord Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten. They listened to him give a speech at a liaison strip for 3 hours and 10 minutes. They were then told that they would be having a training program after just having finished a battle. Typical military.

From February 19th through February 24th Paul writes in his diary “nothing doing.” On February 25th he said that he passed the time reading and horseback riding. He went to the Burma Road and saw dead Japanese soldiers and tanks.

On February 26th the Unit started training and marched to Nampakka where most of the fighting took place. He indicated that the place was really wrecked. February 27th consisted of more training. The next day they were told the Unit would be moving again. On March 1st preparation for moving took place. On March 2nd the 44th PSH tore down the basha and packed their equipment for the move.

On March 3rd the Unit began marching with the 475th 2nd Battalion, who took the brunt of the battle down the Burma Road. Paul said that it was hard walking on the road and they weren’t used to it. In total they marched 16 miles that day. By March 4th the 44th PSH made it to their bivouac area, turning off the Burma Road going over the mountain again at Kutkai another 12 miles. Kutkai is a town and seat of Kutkai Township, in the Shan State of eastern-central Burma. It lies along modern day National Highway 3, approximately 24 kilometers to the north of Lashio. The combined Units marched a distance of about 30 miles and then another 12 miles to Hsenwi, also known as Theinni, was a Shan state in the Northern Shan States in Burma. The capital was Hsenwi town. During World War II, Kutkai was occupied by the Japanese. On September 10, 1944, the Chinese Fourteenth Air Force sent out 45 B-25 Mitchells to bomb Kutkai along with the towns of Tunganhsien, Lingling and Tunghsiangchiao, but the town was abandoned without a fight when the Chinese reached it on February 19, 1945.

On March 5th the combined force arrived at Nawhkam in the Hosa Valley to engage the Japanese in a second campaign.

|

The 44th PSH was on the move to Hsenwi, a town in northern Shan State of Burma, situated near the north bank of the Nam Tu River and now the center of Hsenwi Township in Lashio District. It is 28 miles north of Lashio and 2,100 feet above sea level.

On March 22nd, the 44th moved to an area near Lashio, Burma. Lashio is in the northern Shan State, about 200 kilometers northeast of Mandalay. It is situated on a low mountain spur overlooking the valley of the Yaw River. Loi Leng, the highest mountain of the Shan Hills, is located 45 km to the southeast of Lashio. The 44th set up in a very nice area near a river. With no immediate danger, the Unit was able to spend some time swimming, playing baseball, playing volleyball, and hunting.

On April 18th the other part of the 44th PSH boarded a C-47 and flew over The Hump at an altitude of 13,000 feet. The Unit arrived in Kunming, China the same afternoon after a three to four hour flight. The city was of great significance as a Chinese military center, American air base, and transport terminus for the Burma Road.

The Kunming Airfield in southern China was originally built in 1923, ordered by regional warlord Tang Jiyao. In 1937, the Central Aviation Academy was relocated from Jianqiao Airfield in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China to Kunming due to the outbreak of tye war. In 1941, it became the main base for the 1st American Volunteer Group “Flying Tigers” (and later AVG’s successor unit the U.S. 23rd Fighter Group, after the official U.S. entry into the war), and as the war progressed several major U.S. formations established headquarters at Kunming Airfield. It was also a hub for military and supply flights to and from India and Burma. On April 19th the remaining six members of the 44th PSH moved to a staging area at a nearby airstrip. It appears that on April 20th the six, including Paul Gartner, boarded aircraft and flew to Ledo, India, where they picked up their trucks.

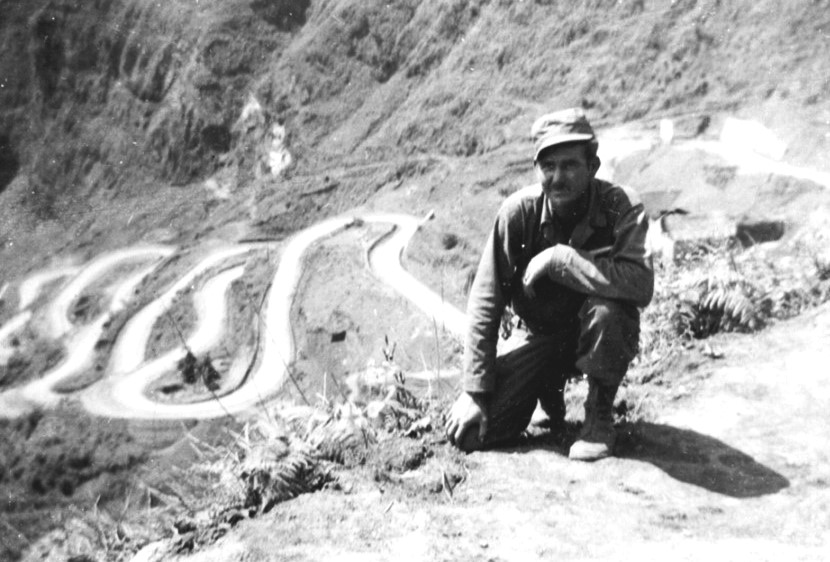

After staying in Ledo for four days, the 44th PSH personnel received orders to join Convoy 94. Paul Gartner recalled that in June of 1944 he had made a similar trip as far as Shingbwiyang and that some of the sights looked familiar. Paul stated that once they began the trip “the road was quite a change after it was made into a four lane highway. After looking and crossing some of the mountains a person would not think it possible to carve a road thru this dense terrain which is probably the worst in the world.”

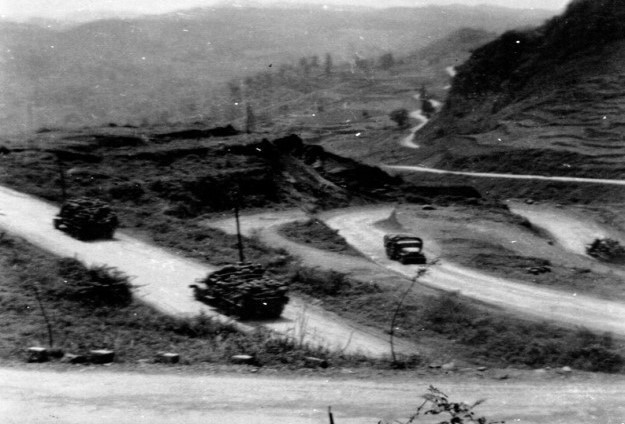

On April 25th the 44th left Ledo via convoy traveling the Ledo Road, with their destination being Kunming, China. Paul wrote, “When we joined the old Burma Road a person could almost tell he was in China by its bare rolling mountains. The population got heavier and it was a pleasure to see lighter complexion on these people. The convoy would drive about 75 miles a day and usually we’d stop in a fair sized village. After bathing in a stream and eating chow, the fellows usually headed for town and buy drinks, which were rare in Burma.”

“On the 7th of May our Convoy finally hit Kunming, China after eleven rough days of driving, arriving at Kunming, China at Hostel 11. The following day we tried to locate our unit but found out that they had already moved 100 miles east from here. We also heard that the unit was split into two groups temporarily and that nine men were on detached service. That left 24 men and 4 officers.”

Victory in Europe Day is the day that the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany’s unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, May 8, 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Eastern Front, with the last shots fired on the May 11th.

“It took another four days to reach the base in Chinkiang on May 12th only to find out again that our unit was already in operation. They certainly lost no time putting us into action. One unit 'A' was operating at Kianko and the other 'B' at Yenchi.” On May 12th the 44th PSH left Kunming for Chinkiang, China to join the rest of the 44th PSH. On May 16th they arrived at Chinkiang they found that the Unit was split into two Units and that they were already in action.“

On May 19th Paul’s Unit left Chinkiang to join up with the other 44th Unit at Kaingkoa, China arriving on May 20th. On the 21st the 44th reached Yenchi, China and by May 30th they arrived at Hsenur, China. Replace with On May 19th they left Chinkiang to join up with the Unit at Kaingkoa, China arriving on May 20th. On the 21st the 44th reached Yenchi, China and by May 30th they arrived at Hsenur, China.

As previously stated, when they arrived they found out that the rest of the 44th PSH left for E.C.C. (Eastern Command Center) Kunming, also known as Yunnan-Fu, which is the capital and largest city of Yunnan province, China. Kunming was increasingly targeted by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAF) when the Burma Road was lost to the Japanese. The 1st American Volunteer Group, known as the “Flying Tigers,” was based in Kunming, and was tasked with defense of The Hump supply-line that stretched over the Himalayas between the British bases in India to port-of-entry Kunming against Japanese aerial interceptions; China’s primary lifeline to the outside world, which had included the Burma Road and the Ledo Road, all with Kunming as the northern terminus.

Paul wrote, “It took the six of us another day to reach Kianko which was 40 miles of very treacherous road. We passed the unit not realizing it and darn near drove to the front lines if it wasn’t for a blown out bridge. It was here where the Chinese made their first offensive. The result was the annihilation of the Jap's 716th Regt. The same day we arrived at the 'A' unit orders were received to pull back to the CCC Hdqs. at Ankiang and then proceed to Yenchi and join the 'B' unit. There were no roads so we all loaded into a river sampan and arrived 85 miles downstream to Tahianko where we proceeded to travel by truck to Yenchi.”

“After helping with battle casualties in Yenchi we had orders to march to Sinwha, which was another 60 miles east. We hired a hundred coolies who carried our equipment on idiot sticks and poles. Some of the heavier supplies came by boat and we had to be pulled up stream by coolies.”

|

|

“About a week later we were assigned to the 73rd Chinese Army to do surgery for them. The building we used was a beautiful three story building which was apparently very new.”

“In a day’s time we set up the hospital after having it scrubbed out and surgery and medical cases were pouring in. The action was taking place in Poaching where the Japs were holding out. At Shinwha we had the town to ourselves with a few other G.I.’s there, which consisted of our Unit and a few Larson teams.” It is believed that the Larson Teams, which Paul refers to, are civilian workers to keep runways open day and night. Captain Harold L. Larson of the Army Air Corp was a commissioned Captain and a civilian personnel officer in Chaubua, Burma (the field from which planes flew The Hump to Free China) in the China-Burma-India Theater. The hired civilian workers were the Larson Teams.

Paul states, “They had a small airfield there also, where the boys played baseball in the evenings. At the time we lived in the hospital and had all the comforts a soldier could wish for. It was our first real break since coming overseas. A few weeks later a school building was fixed up and all the G.I.’s moved in. We had three movies while there and an enlisted men’s bar was built for evening pleasure. The drinks were made by a Chinese person, while the peach brandy was made by some of the fellows.” “Meanwhile 'B' unit came to Shinhwa and stayed for a week and later moved to Lantien to set up a hospital. By this time 'A' unit had admitted close to a thousand Chinese patients and a few G.I.’s with malaria.”

The success of the American and allied forces in the China-Burma-India Theater was contingent on securing transportation routes. The following provides information on these main routes. During the war Paul traveled on all of these routes.

|

Burma Road – Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931 resulted in the Second Sino-Japanese War which continued with sporadic fighting throughout the 1930’s. In 1937 full scale war broke out and Japan occupied most of coastal China. This forced the Chinese to seek another method of brining in supplies and war materials. A route from Kunming, China to a railhead at Lashio, Burma was complete in 1938. Supplies were landed at Rangoon, Burma and brought by rail to Lashio. Built by Chinese laborers stone by stone, this route was known as the Burma Road.

Ledo Road – Japan invaded and occupied Burma in early 1942, blocking the Burma Road supply line. Allied war planners decided to build a new road from Ledo, Assam, India to bypass the cutoff Burma Road, Supplies landed at Karachi and Calcutta, India could be brought by rail to Ledo and trucked over the road to China. This proved to be an extremely difficult task but the Japanese were driven back and a new route forged through northern Burma. The Ledo Road was completed by U.S. Army Engineers in early 1945. It ran 465 miles from Ledo to a junction with the Burma Road at Mongyu, Burma, near Wanting, China. The Ledo Road did not enter China.

Stilwell Road - In addition to building the Ledo Road, Army Engineers and local workers also upgraded over 600 miles of the Burma Road. The Ledo Road and the upgraded portion of the Burma Road from Mongyo to Kunming were later named Stilwell Road at the suggestion of Chinese Generalissimo Chaing Kai-shek, in honor of American General Joseph W, Stilwell, Commander of the China-Burma-India Theater and Chief of Staff to Chiang. The Stilwell Road covered 1,079 miles from Ledo, India to Kunming, China, “470 miles as the crow flies.”

On August 14, 1945, it was announced that Japan had surrendered unconditionally to the Allies, effectively ending World War II. Since then, both August 14 and August 15 have been known as “Victory Over Japan Day,” or simply “V-J Day.” The term has also been used for September 2, 1945, when Japan’s formal surrender took place aboard the U.S.S. Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. Once victory over Japan was declared, every GI wanted to return home.

By 1945, the average American in the service had been overseas for about 16 months; some much longer. Even before Japan was defeated, there was a strong public outcry to bring the boys home, with some even clamoring for a return home by Christmas with the slogan “Home Alive By ’45.”

When the sheer volume of Americans returned are considered — eight million men and women from every service branch, scattered across 55 theaters of war spanning four continents — one can make the case that Operation Magic Carpet stands as one of the greatest achievements of the entire war. Though lasting only 360 days, Operation Magic Carpet was the largest combined air and sealift ever organized.

Operation Magic Carpet officially commenced on September 6, 1945, four days after V-J Day; ending on September 1, 1946. Though on some days and months, particularly December 1945, the return rate was much higher, on average Operation Magic Carpet transported 22,222 Americans home every day for nearly one year straight.

Paul provides the following account: “After a few false alarms Japan finally surrendered and we thought that in no time we would get out of Shinwha. We already had orders to move to Shanghai and Hankow to take care of Allied P.O.W.’s, but both were canceled. We did get orders to move back to Eastern Command at Chenchi. At Chenchi we turned all our excess equipment in.” This took place sometime around September 2, 1945, the date that the Japanese officially surrendered on the U.S.S. Missouri to General Douglas MacArthur.

“Finally orders came thru to move to Hengyang where we were to join the 74th Army. We had hope of Maj. King coming with us, but he was made Eastern Command Surgeon, so he had to stay behind. Capt. Joseph Andrews was put in charge of us.”

“The trip to Hengyang was made by truck and was uneventful until we hit the city of Paoshan. The city was in complete ruins. On the way we hit units of the Chinese 74th Army. You would be amazed at the way they carry their equipment. About 15 would pull a 37 mm gun. They had very few pack horses. In the third day we hit the city of Hengyang, which was more destroyed than Paoshan. The Japanese and Chinese fought for this city for 47 days when the Japs finally captured it. The 10th Chinese Army was completely destroyed, except for a few men who managed to escape thru the Japs Line. Riding thru the main street we bumped into a large column of Japs who were completely armed. They were moving toward Changsha to give up their arms after the official surrender. Our unit set up a temporary surgery and dispensary for the purpose of treating G.I.’s only. One of our men had the misfortune of being burned by an exploding stove and was evacuated the following day by C-46 at the air strip across the river. “

“A message just came through for our unit to proceed immediately to Chinkiang where we wil turn in our supplies and equipment over to the quartermaster. From there we will fly to Kunming. The trip didn’t take long because we knew it meant going home. In two days we reached Chinkiang, but we were delayed four days waiting for air transportation to Kunming, The trip by air was very nice and soon we were billeted in Staging Area 19, called Camp Ting Hoa. After quite some fuss and confusion, thirteen of us were made casuals, while 1st Sgt., Supply Sgt., Cook, and clerk and two low point men stayed behind to form a new unit to bring back to the states.”

“On the 18th of October, we were put on Flight No, 13 on a C-54. The trip was to Calcutta, India and it took five hours to fly there. Trucks were awaiting our arrival and soon we were on our way to Camp Kancharapara for more processing. We stayed up all night handing excess clothing in and also drawing new ones. The sight of camp surprised me due to the great change. Two years ago our unit was one of the first ones here and there were very few tents standing.”

“The stay at Kancharapara was uneventful all except K.P. they had me on. I did manage to go to Calcutta on a pass. After three weeks we were transferred to a new area, and joined the 441st H.A.M. Ord. Co. Just for transportation back to the states. Here we just laid around playing a little baseball.”

“On Nov. 13th the unit was moved to Calcutta at Hialeha race track. The food was wonderful and so was living in the middle of a big city with its beautiful temples and buildings surrounding us. “

|

Paul wrote, “It took a few days to load the rest of the troops on board. We traveled about 100 miles down the Hooghly River and on the 19th of November we hit the Bay of Bengal and the trip was officially started.”

“After three days of beautiful scenery of the Burma Malay (Malayan) and Sumaira (Sumatra) coast we passed Singapore, which I saw through binoculars. The buildings were large and modern and apparently untouched. Soon we were headed northward in the South China Sea. The heat was terrific, but after two years of it didn’t bother the men much. Gradually the weather got cooler and the fellows started getting their jackets out. We were approaching Japan now and we passed a small island. At this time we were 130 miles from Yokohama and slowly heading northeast toward the Aleutians. During this trip I volunteered to work in the officers mess kitchen so I could get some good meals. The work wasn’t too hard.”

“The water near the Aleutians was very rough. Men eating in the troop mess had quite a time holding on to their mess kits due to the rolling and rocking of the ship. At least ten men were hurt from the slippery floor. “

“On the 23rd day of our trip we finally sighted the state of Washington. I just can’t begin to explain the feeling we had in seeing it. I guess it was the happiest moment we’ve felt in a long time. That evening we docked at Tacoma and trucks were there waiting to take us to Fort Lewis Staging area.”

“The stay there was five days long and it was getting nearer to Christmas every day. I had fear we would not make it. We finally had a troop train come there and we were on our last leg of the trip home.”

“With a little trouble we made the trip to Indiantown Gap (Pennsylvania) in 5 days and 6 nights. As soon as we arrived at the Gap, they lost no time in getting us ready to be discharged. The next afternoon at three thirty I raised my hand for the last salute in my army career.”

China-Burma-India Theater ONE SOLDIER’S STORY Adapted from “Survivor to Life Saver” by Donald Gartner and Randy Gartner TOP OF PAGE CBI ORDER OF BATTLE HOSPITAL UNITS IN CBI THE LEDO ROAD PAUL GARTNER PHOTOGRAPHS ROHNA SURVIVORS MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION CONTACT US MORE CBI THEATER |

Copyright © 2024 Donald Gartner and Randy Gartner Adapted by Carl W. Weidenburner Revised: