|

The first convoy over the almost completed Ledo Road would soon be heading for China. Correspondents and others unfamiliar with the road who were to go along with the convoy would have a lot of questions about the road and what they saw along the way.

To answer some of these questions, the Public Relations Office of Advance Section 3 apparently created this mimeographed handout to give background information on the area, the construction of the road, and the leaders responsible for its construction.

On this page is the complete text and illustrations from the original. Many of the figures and examples given were used in news articles and other publications, both during and after the war.

Three of the CBI soldiers who worked on this handout later created the more professional and widely distributed booklet: Stilwell Road - Story of the Ledo Lifeline

First Convoy Over the Ledo Road

The Story of Pick's Pike

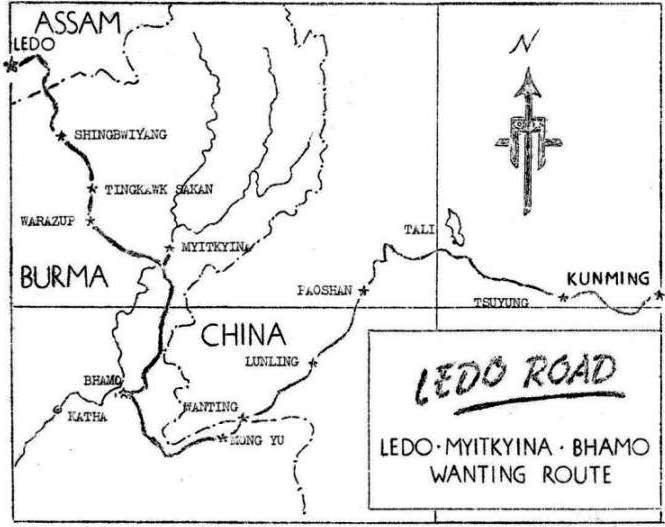

When Burma was invaded by the Japs early in 1942, the Burma Road, last route to China's valiant armies was sealed off and future Allied supplies and assistance overland awaited ambitious military plans and execution. In October, 1942, Lord Wavell (then Field Marshal) made the building of a road an American project and by November 5, 1942 an engineering plan was submitted to General Joseph W. Stilwell with the proposal that the route roughly follow the old Refugee Trail used by the natives in fleeing Burma. It was to start at the small bazaar of Ledo, Assam, India and cross the rugged, forbidding Patkai Range to the Hukawng Valley beyond, making an eventual juncture with the Burma Road. Ledo was selected as the spearhead of the proposed highway since it was near the terminus of the Dibrugarh-Sadiya Railroad over which supplies could be brought from the Indian port of Calcutta. To construct the Ledo Road meant that first the Japs had to be cleared from northern Burma as the artery progressed. Secondly, the building of the highway required cutting through dense, virgin jungles never before traversed by white men and on which only meager geodetical statistics were available. Hundreds of bridges were required to span rivers that turned from dry bed creeks to raging torrents as the monsoon swept the land over which the road ran. Lastly, it was a fight with nature against driving monsoon rains, dread malaria, crawling insects and the heart-breaking, endless obstacles that faced the men building a road 12,000 miles from their American supply sources. Thus the Ledo Road, dubbed "Pick's Pike" after its builder, Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Pick, became a dual purpose project: to supply the Chinese and American forces, fighting to clear the Japs from Burma and to eventually provide a wide, sound highway over which convoys could bring the precious implements of war to our beleaguered Chinese allies. The Ledo Road was started about December 1, 1942. Working from that time until now, American Army Engineers along with their buddies in every branch of the service, have pushed this mighty military engineering project toward completion. With the rolling of the initial convoy from India to China, these two countries will be linked by a suitable route for the first time in history. As the maps herein indicate, future supplies will roll over the Ledo Road from the little, squat town - now made world famous, on to Myitkyina, Burma, scene of one of the bloodiest sieges in this part of the world, to Bhamo and then to Wanting on the China-Burma border. From there the route follows the old Burma Road, now rebuilt to accommodate truck convoys. The following pages give complete facts and data on the Ledo Road, Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Pick, famous Army engineer in charge of the project, and the thousands of American soldiers that make the first convoy joining China with her fighting allies possible.

[The information contained herein has been passed for publication by the Press Censor, USF in IBT.] |

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA on LT. GEN. DAN I. SULTAN VITAL STATISTICS: Lt. Gen. Dan I. Sultan was born on December 9, 1885, at Oxford, Miss. He married Florence Braden of West Point, N.Y. in 1916. He has two daughters, one of whom is married to an Army officer and the other in war work in the U.S. EDUCATION: Attended the University of Mississippi for a year and a half, then entered West Point in 1903. He graduated in 1907 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. MILITARY SERVICE: During World War I Gen. Sultan was a member of the War Department General Staff and served in France as a General Staff Officer. During 1942 and 1943 he was Commanding General of the 8th Corps. Late in 1943 he was sent to the China-Burma-India Theater as Deputy Theater Commander to Gen. Stilwell. He was promoted to Lieutenant General of September 2, 1944. On October 26, 1944 he assumed command of the India-Burma Theater.

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA on MAJ. GEN. W. E. R. COVELL VITAL STATISTICS: Major Gen. W. E. R. Covell was born on the 29th of November, 1892. Crossett, Arkansas, is now his home. EDUCATION: Number one honor graduate of the Class of 1915 at West Point, a distinguished class which included Generals Eisenhower and Stratemeyer. Received a B.S. at M.I.T. in 1923. Attended the Command and General Staff School in 1930. MILITARY SERVICE: General Covell has seen a remarkably successful Army engineering career. Among his jobs was the one of District Engineer at Pittsburgh where he was responsible for instituting a large part of the flood control program in that area. In July, 1935, he retired from the Army at his own request to become General Manager of the Crosset Arkansas Industries, manufacturers of lumber and chemicals. Came back on active duty in June, 1941, and since November, 1943, has been Commanding General of the Services of Supply in the India-Burma Theater.

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA on BRIG. GEN. LEWIS A. PICK VITAL STATISTICS: Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Pick was born at Brookneal, Virginia, November 18, 1890. Married to Alice Cary Pick, he has one son, Lewis A. Pick, II, age 17 years. EDUCATION: Attended Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 1914 to 1917. Graduated as a civil engineer. In 1923 to 1924 attended Engineer School, Fort Belvoir, Va. 1932-1934 he attended the Student Command and General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. 1938 to 1939 he was a student at the Army War College, Washington, D.C. MILITARY SERVICE: General Pick entered military service May 15, 1917 and was in training from this date until August 15, 1917. From November 1917 to June 1919 he was company commander of the 23rd Engineers. He served in the Meuse Argonne Offensive with the 1st Army of the AEF. As a full colonel he was assigned to this base October 16, 1943 and made Brig. Gen. on February 21, 1944. FACTS OF INTEREST: As division Engineer, Missouri River Division, Omaha, Nebraska, March 1942 to September 1943, General Pick was in immediate charge of war construction in nine states of the Missouri River Valley amounting to 1½ billion dollars. In 1943 he developed the "Pick Plan" for the comprehensive development of the Missouri River for flood control, navigation, hydro-electric power and irrigation to cost about 1 billion dollars as a post-war undertaking for the employment of men on a worthwhile project. During the many months that he supervised construction of the road, the General invariably carried a stick, cut from the jungle. As a result, to the soldiers he commanded along the Ledo Road, he became known as "Pick, the man with the stick," aptly describing the driving force he displayed in pushing ahead this immense engineering project. General Pick spent considerable time in the field working in close touch with the road building engineers, and as a result had several narrow escapes from death. On one occasion, the General while inspecting road progress in the forward area was strafed by Jap planes. In July, 1944, at Myitkyina, Burma, during the siege of the Jap held town, the General had just alighted from his plane when a cargo ship coming in for a landing crashed into it, completely demolishing the craft. |

|

History of the Ledo Road Project

FOREWORD The Ledo base area is located in the northeastern tip of Assam in the Brahmaputra River Valley where the Buri-Dehing River flows from the jungle-covered foothills of the Patkai Mountain Range. These Naga Hills, named after the primitive head-hunting aborigines which inhabit them, rise in ranges up to 7,000 feet, from the low hills south of the bazaar of Ledo, where the Dibrugarh-Sadiya Railroad line terminates, to the higher peeks beyond the Burma border. Although the temperature is moderate, the climate of Assam is penetratingly cold during the winter and exceptionally humid the year around. During the height of the monsoon the heat is intense. Violent tropical showers and electrical storms are frequent occurrences. The yearly rainfall ranges from a 140-inch average in the hills to 110-120 inches in the Ledo valley area. Some monsoon seasons, however, bring rainfall greatly in excess of these figures as in 1944 when 175 inches of rain were recorded in the mountains. It was in this remote corner of the world that American engineers were given a job to do - a job which the British had tried and branded as "impossible." The history of this job - the Ledo Road project - has three distinct phases: The British Period, The Early U.S. Period and the Completion Period. BRITISH PERIOD March 8, 1942, the Japanese Armies took Rangoon and throttled off China's last route of land supply with the closing of the Burma Road. It was obvious that a new route of land supply would have to be opened if the United States were to carry out its commitments to China. Early routes which were checked included the North Afghan and Trans-Iranian routes, both of which would utilize Russia's Central Asian Railway, and both of which were long and involved with diplomatic complications on the question of neutrality between Russia and Japan. The Manipur Road was ruled out as a China supply route because the Japs were firmly entrenched in Burma below the road. The British started work on a route from Ledo in the general direction of Fort Hertz in February, 1942. A second route stemming from Ledo up over the Patkai Mountains and down through the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys of northern Burma had been surveyed several years before. In 1942 this was planned only as a "jeep" route, but today it is the route which has become known as the Ledo Road. In April, 1942 Colonel Russell A. Osmun and Lt. Col. Fabius H. Kohloss, accompanied by three other officers, surveyed this route, in which Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek had become interested. They reported that the British had stopped work on the truck route to Fort Hertz, and it was decided that future Allied road building efforts would be concentrated on the route of the Ledo Road. Originally it was planned to have Chinese labor build northward from Mogaung, and the British build east and south from Ledo. Japanese penetration of northern Burma soon ruled out the possibility of the Chinese effort. In October, 1942, General Stilwell and Field Marshal Lord Wavell (then General Wavell) met and decided that the construction of the Ledo Road would be an American responsibility, subject to the approval of the Generalissimo, from which it would be necessary to obtain the release of Lend-Lease stores of road building equipment which could not be moved into China. Subsequently, American Army officials met in Delhi and drew up plans for the Ledo Road project which were submitted to Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell on November 5, 1942. These plans were indefinite, but it was generally accepted that the route of the road would roughly follow the Refugee Trail to Shingbwiyang on the edge of Burma's Hukawng Valley. The Refugee Trail, an ancient Naga route between Burma and India across the Patkai Mountains, was used by refugees fleeing into India before the Jap tide of aggression early in 1942. On December 1, 1942, the advance contingent of American troops arrived in Ledo and went to work on the road with the British Engineers, who had, by that time, cut the road to a point which is now Mile 0.00 on the Ledo Road. On December 10, 1942, the road became officially an American project.

EARLY U.S. PERIOD Tea plantations and matted, virgin jungle were turned into bivouac areas by the first detachment of colored American engineers to arrive in Ledo in December, 1942. Utilizing a handful of bulldozers and a fleet of dilapidated British lorries, the engineers set to work pushing the road up into the Patkais from the Mile 0.00 mark. By January 1, 1943, the lead bulldozer was at Mile 15. In an effort to make as much progress as possible before the onset of the monsoon, access roads and maintenance operations were discarded as the engineers pushed one road head on up into the mountains. When a critical shortage of heavy equipment threatened to impede progress of the road trace, Indian laborers were imported in large numbers. These laborers - Kachin and Travencore coolies, workers from the tea plantations of Assam and Bengal, porters from the Garo and Darjeeling hill country - cleared the new trace by hand. Although their labor accomplished a useful purpose, it was never wholly satisfactory. Most of the men were untrained, and the term of their contract ran for only three to six months. At the expiration of these contracts, the men usually returned to their homes, thereby necessitating the hiring of new, untrained laborers. Often, labor contracts stipulated that men be stationed in high altitudes to which they were unaccustomed. This created a problem in the placement of workers. In the early days of the project, not more than 250 vehicles were available. These included three 6x6's (GMC 2½-ton cargo trucks), a few dump trucks and an ill assortment of conveyances acquired from the British, including 100 lorries which were on the deadline most of the time. At one period, trucks were kept on the road only by resorting to cannibalization, a practice which consists of appropriating enough parts from one truck to keep others running. On February 26, 1943, the lead bulldozer crossed over Pangsau Pass into Burma - Mile 38.50 of the new trace. That evening a formal retreat with flags and bugles was held by the officers and enlisted men of the engineering units attached at the point, celebrating the entrance into Burma. Supply of the engineers working in the forward area was a big headache. Native porters and Chinese mule pack trains augmented the inadequate fleet of trucks. And, after the first rains of the impending monsoon season turned the new trace into a quagmire in mid-March, all supplies were carried into the jungle by porters, as even the mules (Indian Tonga ponies) bogged down in the mud, cut and broke legs and fell over sheer cliffs on Pangsau Pass. By the end of March, the lead bulldozer, operated by fuel carried up to the point by porters, was at Mile 47.3. Heavy rains impeded work on the new trace as engineers battled to maintain and hold the roadway they already had cut against the encroachments of the torrential downpours. On March 31, 1943, a large Japanese patrol was reported beyond the point of the road. Security patrols were sent out by the engineers but were withdrawn in three weeks when no contact was made with the enemy. Later it was learned that a large contingent of Japs had advanced beyond Tagap (Mile 79.40) but were forced to withdraw to their supply base at Shingbwiyang when their native porters and elephant contractors deserted the expedition, taking the elephants with them. This marked the farthest penetration by the Japs toward the American supply base of Ledo. The road had advanced to Mile 42.5 before work bogged down with the onslaught of the monsoon. Prior to the advent of the rains, the first sub-depot was set up at Hell Gate (Mile 30.78). After the monsoon made even the native porter supply line a precarious and uncertain affair, air-dropping units were organized and supplies were dropped to the forward units by parachute. Engineers at the point underwent untold hardships during the rains, men were wet all the time. They slept in water-logged tents, bamboo lean-tos and jungle hammocks. The soggy jungles were infested with long, purplish leeches, the bites of which festered. Dozers were lost over steep banks when rain-saturated trace shelves collapsed. Dozers were buried in slides and stalled in seemingly bottomless mud. COMPLETION PERIOD When Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Pick assumed command of the Ledo Road project on October 13, 1943, progress on the road seemed hopelessly stalled in a maize of densely jungled, precipitous mountains. Eighty percent of the engineering company at the point was hospitalized with malaria. Crews were working but one eight-hour shift a day. General Pick, who had been called from his command of a vast construction program being carried on by the Missouri River Division and his work with Missouri Valley Flood Control to assume command of the Ledo Road project, held a staff meeting in the officers' mess hall his first evening in Ledo. "I've heard the same story all the way from the States," he told his staff. "It's always the same - the Ledo Road can't be built. Too much mud, too much rain, too much malaria. From now on we're forgetting this defeatist spirit. The Ledo Road is going to be built, mud ran and malaria be damned!" The General's first act was to move Road Headquarters up to the point. Next he instituted a "round-the-clock" working schedule. When he was told that there was no light for working nights, he rounded up all available lighting equipment on the base and shipped it forward. When this proved inadequate, he inaugurated a method of burning flares in buckets of oil. This method is still widely used for night work along the road. General Pick had moved up to Road Headquarters when Gen. Stilwell paid his first visit. They met in a rain-soaked tent which served as General Pick's jungle office. "Where are your detail maps? Gen. Stilwell asked. "I have none," Gen. Pick said. "Where are your progress charts?" "I have none." "Where is the point of the road now?" Gen. Pick took a small scale map and marked a point in the shaded Patkai Mountain sector. "Here, at the 50-mile mark," he said. Gen. Stilwell studied the map for a moment, then asked, "When can you build me a jeep road to Shingbwiyang?" "I can't build you a jeep road," Gen. Pick answered. "But I'll build you a military highway to handle truck traffic." "And when can you get the truck road through to Shingbwiyang?" "When do you want it?" Gen. Pick countered. "Can you get it through by January 1st?" Stilwell asked. Gen. Pick said "Okay." Then gen. Stilwell and Gen. Pick hiked up to the point. They labored through knee-deep mud, passing dozers stalled in mud up to the stacks. When they returned Gen. Stilwell turned to Gen. Pick and asked, "When did you say you'd get the road through to Shingbwiyang?" "By the first of the year," Gen. Pick replied. That first meeting took place November 3, 1943. On the morning of December 27, 1943, the lead bulldozer broke the tape at Shingbwiyang in Burma's Hukawng Valley, and the engineers had conquered the Patkais four days ahead of schedule. A convoy of 55 trucks carrying Chinese combat troops and equipment followed the lead dozer into Shingbwiyang, marking the first Allied troops to be brought into North Burma by vehicle. Later in the day a celebration was held for members of the engineer regiment which had cut 54 miles of trace through the roughest terrain in the world in 57 days. The celebration was held at an engineering camp on Chinglo Hill, at Mile 95.65. Special Service provided a band, a stage show, movies, a mimeograph newspaper setup, PX supplies and food. And, with the Jap front lines less than 20 miles away, the American GI's celebrated the historic occasion. A major sub-depot, under the direction of Lt. Col. Robert A. Hirshfield, was set up at Shingbwiyang to augment smaller depots at Loglai and Tagap - Miles 50.86 and 79.40. The opening of the road through the Patkais provided a route for Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell's combined Chinese-American combat forces to enter North Burma in strength. During January, Chinese units moved up from India to the front, and in February Brig. Gen. Frank Merrill's famed Marauders made their famous 10-day march over the mountains and started their now-legendary assault on the Nip invincibility myth. To make this Allied offensive possible, Gen. Pick diverted a large percentage of his engineers from work on the Ledo Road trace to clear combat road through the jungle to the front over which troops and supplies and tanks and equipment could move. Engineers, working on armor-plated bulldozers, went in advance of the infantry, cutting a trace which eventually led through the jungle to battlefields at Ningam Sakan, Taipha Ga, Maingkwan, Walawbum, Tingkawk Sakan, Jambu Bum Pass, Shadazup and Warazup. As the tide of battle swept on into North Burma, engineers pushed the Ledo Road trace on down the Hukawng Valley. Although at several points the lead bulldozer was held up by the combat situation, progress was rapid. The lead bulldozer averaged better than a mile a day. Chinese engineers built bridges of hand-hewn timber over the many streams which the road crossed. These bridges, all intended as temporary crossings, later were replaced by H-20 and Bailey steel bridges. As the point moved forward other engineer units were at work in the Patkais, eliminating bad curves, making new fills and setting up a road drainage system. By the time the 1944 monsoon struck North Burma, the road distance between Ledo and Shingbwiyang had been whittled down from 117 to 102 miles. The road had progressed to Warazup (Mile 189.20) when the 1944 monsoon held up further forward progress of the point. Further advance of the lead bulldozer beyond Warazup before the advent of the monsoon had been impossible because of the combat situation and the use of road engineers in the construction of combat trace and airfields. Save for occasional road blocks, the road was kept open during the rains. In fact, the road not only was kept open for truck convoys, but the first sizeable shipments of heavy equipment to arrive in Ledo from the States were moved up the road during the monsoon to forward points where it could be put into operation at once on the new trace when the rains ended. Thus, the end of the monsoon in October found a vast backlog of new bulldozers, trucks, cranes, shovels, carry-alls, rock crushers, culvert, bridge sections and all the myriad vital engineering equipment which goes into the construction of a highway poised at Warazup ready for the drive down the home stretch. While Gen. Pick's engineers were waging a successful battle against the weather, the Japs were driven further and further back south into Burma. Kamaing fell. Mogaung fell. Two battalions of Ledo Road combat engineers were flown in to help the infantry in the Battle of Myitkyina in May. And, after a 74-day siege, that vital Irrawaddy River bastion fell to combined American-Chinese forces. Although the rains halted the lead bulldozers, survey crews continued to probe through the matted jungle, across swamplands and over the low, rolling hills which fringe the Mogaung and Irrawaddy River valleys, surveying the route laid out by Gen. Pick. And, during the rains, engineers completed the biggest job of maintenance engineering in the history of the Corps of Engineers, the construction of a two-mile wooden causeway over a stretch of flooded jungle land. This causeway - comprised of 1,000,000 board feet of lumber cut by two GI lumber mills in the Hukawng Valley - was built across a low-lying section of the valley inundated with four to six feet of water. Working day and night, the engineers completed the causeway in 40 days and averted a serious stoppage in the flow of supplies. With the end of the monsoon, all the crack engineering units on the Ledo Road began the new trace. Chinese engineers built a corduroy access road across 10 miles of swampland south of Warazup and up into the foothills. The rough access road then followed the proposed route along hillsides and down into Namti, a station on the Rangoon-Mandalay-Myitkyina railway, halfway between Myitkyina and Mogaung. Leap-frogging along this access road, units would build a four or five mile stretch of roadway, then move forward ahead of other units and start new traces. The engineers worked around the clock. Mobile generators supplies power for huge floodlights. Supplemented by the oil flare pots, night was turned into day in the middle of the Burma jungle. Long lines of bulldozers pulling carry-alls and huge, lumbering tournapull prime earth movers chewed away at the mountainside as tons of earth were moved into the swamplands where 15-foot-high dirt causeways were built across areas which are inundated with five to ten feet of water during the monsoon. And, all through this causeway system a network of culvert was installed to provide proper flood control during the rains. Simultaneously, other engineers pushed through a combat road from Warazup to Kamaing, where a Jap-constructed trace led down to Mogaung and skirted the railroad to Namti and Myitkyina. Using this rough, narrow road, convoys of supplies and equipment, tanks and artillery were soon moving from Ledo to Myitkyina. The two engineering battalions which had fought at Myitkyina were re-equipped. One was detailed the job of strengthening bridges in the Hukawng Valley. The other was given the job of pushing the road south of Myitkyina to Bhamo, keeping the point right behind the advancing infantry. In fact, the engineers sent out crews of men with mine detectors in advance of their lead dozers. Thus, mid-November of 1944 saw a chain of veteran Ledo Road engineers building the highway from the swamplands and hills south of Warazup to the rice paddies of the Bhamo sector. After the fall of Bhamo in December, 1944, the engineers moved on toward the Namhkan-Wanting area, improving a rough, narrow road to handle heavy convoy traffic into China. These engineers worked on the fringe of enemy-held territory, sometimes within sight of the front lines. In the final summation, during the first ten months of the Ledo Road project 42 miles of road were built. In the next 15-month period, after Gen. Pick took over command of the project, 436 miles of road were built and improved, from Pangsau Pass to Wanting on the China-Burma border, as well as three major airfields. American engineers had accomplished a task which had been branded "impossible" - constructed a permanent, all-weather supply highway to China from India, through towering jungled mountains and across swamplands and rice paddies, despite the heaviest rainfall in the world. Today the Ledo Road is 478 miles of modern American engineering skill stretched across the broad green tapestry of a remote uncharted jungle world, a lifeline to sustain the Chinese in their battle against the evils of totalitarian aggression. And, as the first convoy over the Ledo Road to China left the Mile 0.00 post at the railhead of Ledo and began its long journey, Gen. Pick paid his tribute to the men whose devotion to duty had been the staunch spirit of the Ledo Road Project. He said, "If there's a better Road Gang, I'd find them!"

|

|

|

Engineering and Construction Data

The following facts are relative to the construction of the Road from Ledo, Assam to the junction of the Burma Road. The Ledo Road which forms an overland route from the ports of India to the interior of China was constructed at the end of the longest supply line in the world with too few troops and never enough equipment from the very outset of the project. There were neither records nor means of securing information as to the topography, types of soil, road materials, amounts of rain, or the characteristics of the rivers that were to be encountered and the jungles through which the Road passed were too thick to permit more than a rough location of the route to be followed. Work was started on the Ledo Road in December of 1942 but the initial progress was slow. When General Pick assumed command of the construction of the Road in October of 1943, the lead bulldozers crashed into the jungles at the forty-five mile mark with the construction troops following and, after fifteen months of around the clock grinding through jungles, mud and monsoon rains, today there is a highway linking that jumping-off point with the Burma Road. CONSTRUCTION PROGRESS and RAINFALL From October of 1943 to January of 1945, the Road was completed from the forty-five mile mark to the junction of the Burma Road which is a distance of 420 miles, and the first 45 miles was straightened, widened and the surfacing improved. This represents progress of about one mile of road completed per day over a route that passes through 102 miles of mountain section containing two approximately 4,000-foot passes. During seven months (March through October, 1944) of the fifteen month construction period, 175 inches of rain fell in the mountains and 100 inches of rain were recorded in the Valley. By way of comparison, the east coast of the United States has an average of less than 45 inches of rain annually. In addition to the remarkable rate of progress maintained on the Ledo Road proper, the construction troops were called upon to build several hundred miles of combat roads, temporary supply roads, pack trails, and access roads. AIRFIELD and OTHER CONSTRUCTION ACTIVITIES While the construction of roads was the designated mission of the troops who have completed this vital link between India and the Burma Road, this is, by no means, an indication of the total accomplishments in the field of construction during this fifteen month period. Four airfields were constructed having a combined seal-coat surfaced runway area of about 340,000 square yards or approximately 70 acres. In addition to the main runways, it was necessary to construct, at each of the four airfields, thousands of feet of taxi ways leading to surfaced aprons, revetments and dispersed parking areas which more than doubled the area surfaced for the runways proper. Numerous liaison strips were also constructed along the route to support combat and supply operations. In support of the construction troops and the combat forces, it was necessary to provide housing facilities for thousands of men; hospitals for the sick and wounded; and several million square feet of covered warehouse space. Added to all of this tremendous quantity of work were the problems of providing signal communications for a constantly extending line of supply; furnishing manpower to provide sanitary facilities essential to the never ending fight against tropical diseases; and constructing recreational facilities for use by the men during their far too fee off-duty hours. EARTH MOVED and CULVERT INSTALLATION Almost unbelievable quantities of earth had to be moved in order to push the Ledo Road through the 270 miles of virgin jungle to the junction with the Bhamo Road and, to handle drainage, train load after train load of culvert pipe had to be moved into Ledo and then down the Road to the points at which it was used. Through the 102 miles of mountain section where the minimum shoulder to shoulder width of the Road is 33 feet, 100,000 cubic yards of dirt were moved for each mile of road constructed. In the valley, where 49 feet is the minimum shoulder to shoulder width, 25,000 cubic yards were moved per mile. In round figures, an average of 50,000 cubic yards of earth were moved for each completed mile of the Ledo Road which is a total of roughly 13,500,000 cubic yards. With this amount of dirt, it would be possible to build a solid dirt wall three feet wide and ten feet high in a straight line from New York City to San Francisco, California. If the culvert pipe used in the drainage system of the Ledo Road were placed end to end, it would form a continuous pipe 105 miles long which is about a quarter of the entire length of the Road. It is estimated that an average of 1200 feet of culvert were installed for each mile of the Road. ROAD SURFACING PROBLEMS The earth over which the Ledo Road passes is a sandy loam that whips into liquid mud which requires a heavy surfacing coat to withstand the pounding of convoys. Such rock as is available in the mountain sections has shale-like properties and soon grinds into a powder if used for a surfacing material. Therefore, gravel deposits in the rivers along the Ledo Road furnished the only source of surfacing material. Recovering gravel from the streams along with the haul and spreading constituted a major accomplishment in itself. It was sometimes necessary to transport gravel as far as 25 to 30 miles. In the 102 miles of mountain section, gravel was placed 12" deep over a 20 foot section amounting to about 3,865 cubic yards of gravel per mile to take care of settlement, shrinkage, was and initial patching. A total of 5,785 cubic yards per mile. On the 265 miles of virgin road through the valley (Shingbwiyang to Bhamo) and on the 98 miles of road from that point to the junction with the Burma Road, 8" of gravel were spread over a 20 foot section or about 2,580 cubic yards to the mile. The initial maintenance here required an additional 860 cubic yards of gravel per mile for a total of 3,440 cubic yards placed on each mile of road. It would take at least 1,100 fifty-car trainloads or a string of railroad cars 470 miles long to move the over 1,383,000 cubic yards of gravel which were placed on the Ledo Road between Ledo and the junction of the Burma Road. BRIDGES and RIVER CROSSINGS The rivers which cross the Ledo Road, due to their number, width, and volume of water and drift they carry in the monsoon season, presented seemingly insurmountable barriers to the completion of the Road. The Road crosses 10 major rivers between Ledo and the junction of the Burma Road. From Ledo forward, these are the Tirap, Namyang, Namyung, Tarung, Tawang, Tanai, Mogaung, Irrawaddy, Taping and the Shwelhi. Not considering the numerous minor drainage lines and small creeks which had to be contended with, and in addition to the major rivers, approximately 155 secondary streams had to be bridged before truck traffic could reach the Burma Road. In other words, there is a bridge crossing either a major or a secondary river for about every 3 miles of road constructed. While temporary bridges and pontoon bridges had to be constructed to meet the demands of the tactical situation, these have all been replaced by permanent, two-way, pile driven bridges capable of carrying maximum contemplated loads. There are in all about 165 main bridges on the Ledo Road exclusive of the crossings over minor drainage lines. Total overall length of these bridges is about five miles. At the Irrawaddy River one of the longest pontoon bridges on record was placed to supply the forward operations until the permanent bridge could be constructed. The permanent bridge had to be a specially designed floating bridge as the Irrawaddy is 60 feet deep at the crossing and fluctuates 45 feet between high and low river stages. LUMBER and LOGGING OPERATIONS Lumbering and logging operations followed the Road point as it pushed south to meet the Burma Road. Demands for forest products in the form of piling, bridge timbers, planking and lumber for the construction of sub-depots along the route reached proportions almost beyond imagination. When monsoon rains required the building of a two mile causeway, over 2,400 piling and 1,000,000 board feet of lumber were cut, sawed, delivered and put into place within a thirty day period. It is estimated that over 822,000 cubic feet of lumber has been taken from the jungles with limited logging facilities available for the construction of the Ledo Road. NATIVE LABOR Thousands of natives were employed in the construction of the Ledo Road, the building of bases and sub-depots, handling supplies and in anti-malaria work. Amazing problems arose in handling of this labor as the individuals comprising this force came from every religion and caste from all over India. The force included Nepalese, Travancoreans, Garos, Bengalese and Assamese as well as troops from the Indian Pioneer Corps. The troubles brought about by language differences alone were almost unbelievable. Each of India's 200 dialects were represented and often sign language had to be resorted to as the only solution to the problem. It was necessary for the Quartermaster to stock a dozen different types of rations and, due to castes and customs, strict segregation of groups had to be carried out. By way of example, there were self feeders who refused to eat food prepared by another lest he become a brother and claim all his possessions. Thousands of tiny fires were scattered through the jungles as individual meals were prepared.

|

Strategic Import of Road Probably never before in military history have operations required such dove-tailing of interests as in the building of the Ledo Road. Unless the Japs were cleared the Road could not have progressed, and without the Road the combat troops could not have pushed back the enemy. Only during the first 42 miles of construction was the road over friendly terrain. With the crossing into Burma in March, 1943, the life-line entered the enemy held territory and from then on its soldier builders were subjected to Jap ambushes, artillery fire, land mines, bombing, strafing and sniping. Moving closely behind the combat troops, the road was the thin thread that supplied our fighting forces as they routed the determined Nips from bunkers and entrenchments, occupied for more than two years. Lead bulldozers were armor-plated and at times engineering soldiers went ahead of the combat men to clear trails so that American and Chinese could reach the dug-in Japs. The road made possible the movement of tanks and heavy artillery pieces and as the project progressed, it was possible to build and supply new airstrips to give active aerial support to our ground troops. In addition to the main highway, countless miles of combat trails and feeder roads were built. From Shingbwiyang, Burma, a combat road was 'dozed out of the jungle to open a route for Merrill's Marauders in their famous drive to Myitkyina. Simultaneously with this effort, the main Ledo Road was kept under constant construction for eventual use by convoys going forward. |

CONVOY FACTS . . . The men who have driven the big trucks up the Ledo Road through all kinds of weather, bringing supplies and equipment to the men in the forward areas, have played as important -- and as grueling -- a part in this vast project as the men who operated the dozers and graders or carried on the battle against the Japs. At times these drivers, colored and white, took their trucks through slide areas with showers of rocks raining down on their vehicles. They ran supplies up to the front lines, undergoing sniper and artillery fire and strafing attacks on many occasions. They wheeled their trucks up and down the steep, slippery mountain roads and sweated out long hours in  the cabs as bulldozers laboriously pulled the convoys through fender-deep mud. They worked long hours, day after day,

stopping beside the road to eat cold rations and steal a few hours sleep.

the cabs as bulldozers laboriously pulled the convoys through fender-deep mud. They worked long hours, day after day,

stopping beside the road to eat cold rations and steal a few hours sleep.

Through it all they have kept up a high degree of morale and developed a fresh road vernacular all their own. A few of their expressions are: COWBOY - A driver who like to drive fast, take chances on the mountain roads. Cowboying is the "art of reckless driving." GAS HAPPY - A driver who isn't content unless he's speeding. FOOT IN THE GAS TANK - Speeding. GETTIN' 'EM - Shifting gears correctly - a highly prized art among the drivers.

TANK ONE - To drive a truck into a bank when it goes out of control in the mountains. PUT HER DOWN - To abandon your truck when it is out of control in the mountains, leaving it to crash over the roadside and down into the gorges below. BOOTIN' IT - To drive along at a steady, mile-eating pace. GUTTIN' IT - To drive fast around curves in the mountains. TOP IT - To get over a grade without having to shift gears. Drivers try to speed up going down a hill so they can get over the next hill without shifting. COCKPIT DRIVER - A driver who out-cowboys the cowboys of the road. WAVE YOUR BACK WHEELS - To pass another truck and leave it far behind. |

|

|

|