Ledo, Assam, India where Dad served was headquarters for northern Burma operations and the Ledo Road. The Forgotten Theater Officially established 3 March 1942, the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations (CBI) is often referred to as the Forgotten Theater of World War II. The  European, Mediterranean, and Pacific theaters received more supplies, more manpower,

and more publicity than did CBI. Of the 12.3 million Americans under arms at the height

of mobilization, only about 250,000 were assigned to CBI and comparitively few Americans

were in combat in China, Burma, or India.

CBI was important however to the overall Allied war effort because

of early plans to base air and naval forces in China for an eventual assault

on Japan. Allied forces, mostly British, Chinese, and Indian, also

engaged large numbers of Japanese troops that might have otherwise been

used elsewhere. America's major contribution in CBI was war materials

and the manpower to get it to where it was needed. Army Air Forces flew

supplies to China while Army Engineers built the Ledo Road to open up a

land supply route. Except for stories of "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell,

Merrill's Maurauders, and a few others, CBI did not often make headlines

in the newspapers back home. The early importance of CBI quickly faded as the war progressed.

Thus the Forgotten Theater label that remains to this day.

European, Mediterranean, and Pacific theaters received more supplies, more manpower,

and more publicity than did CBI. Of the 12.3 million Americans under arms at the height

of mobilization, only about 250,000 were assigned to CBI and comparitively few Americans

were in combat in China, Burma, or India.

CBI was important however to the overall Allied war effort because

of early plans to base air and naval forces in China for an eventual assault

on Japan. Allied forces, mostly British, Chinese, and Indian, also

engaged large numbers of Japanese troops that might have otherwise been

used elsewhere. America's major contribution in CBI was war materials

and the manpower to get it to where it was needed. Army Air Forces flew

supplies to China while Army Engineers built the Ledo Road to open up a

land supply route. Except for stories of "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell,

Merrill's Maurauders, and a few others, CBI did not often make headlines

in the newspapers back home. The early importance of CBI quickly faded as the war progressed.

Thus the Forgotten Theater label that remains to this day.

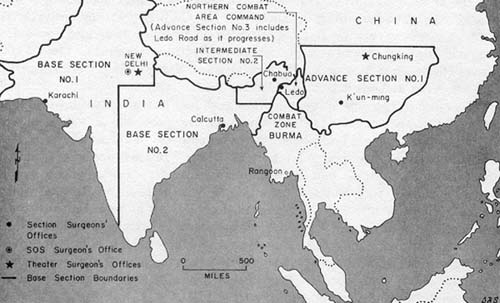

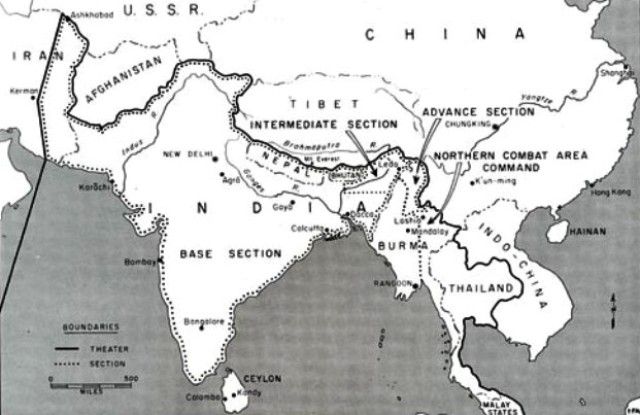

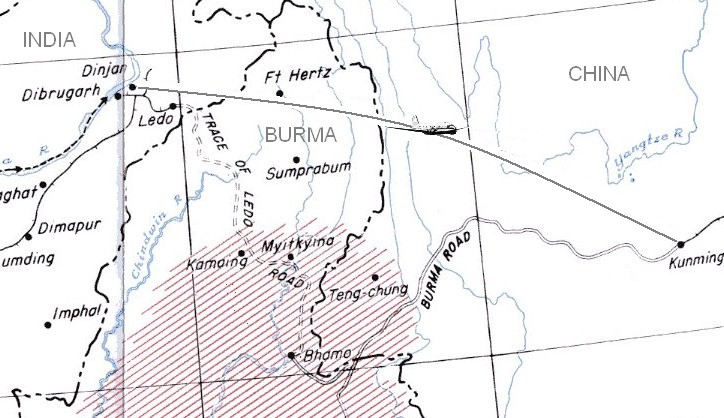

Map shows boundaries revised as the war progressed

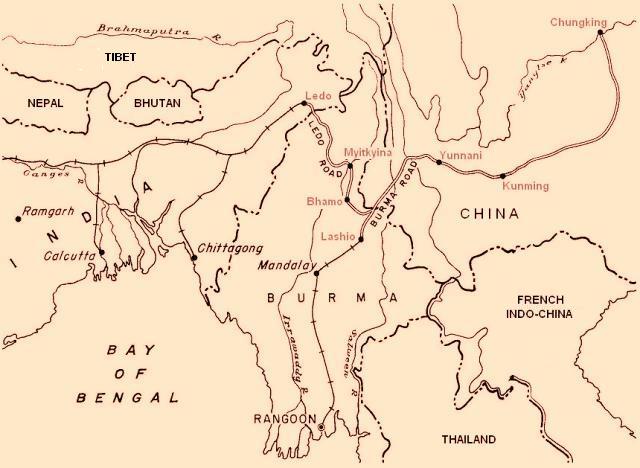

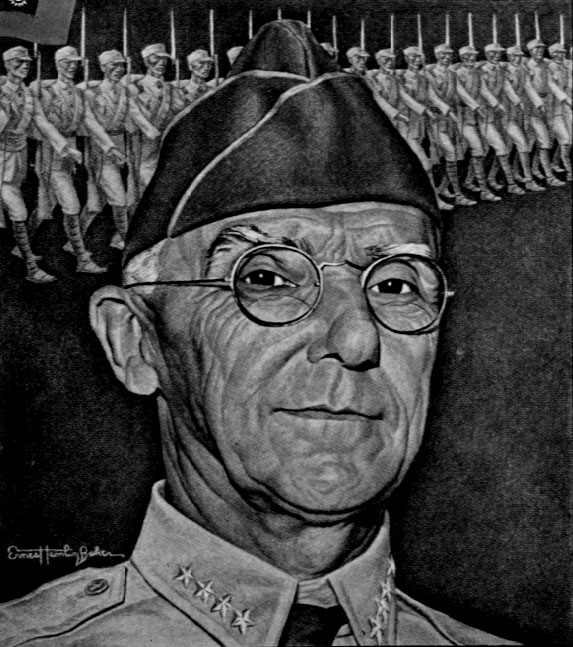

General Joseph W. Stilwell  The Ledo Road was built by American Engineers who called it Pick's Pike after General Lewis A. Pick. It was intended to bypass the cutoff portion of the supply line to China. After completion it and the upgraded portion of the Burma Road were renamed Stilwell Road after the American Commanding General Joseph W. Stilwell. The Ledo Road The United States began to help China defend itself even before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Lend-lease aid began in April of 1941 and in June the American Volunteer Group (The Flying Tigers) was sent to fly missions against the Japanese. Because of Japanese advances in China, Indochina, and Burma, getting lend-lease supplies to China proved difficult. The Japanese had essentially blocked all access to Chinese ports. By May of 1942 Japan had cut the Burma Road supply line and occupied most of Burma. The Burma Road was built by the Chinese during the Sino-Japanese War. It ran from Kunming, China to Lashio in Burma. Lashio was the railhead of a line from Rangoon. War supplies landed at Rangoon were transported by rail to Lashio and then over the Burma Road to Kunming. With Rangoon blocked, an alternative supply route was needed. General Stilwell's operations officer, Lieutenant Colonel Frank D. Merrill  recommended building a road from Ledo, Assam, India, across northern Burma

to link up with the Burma Road. Ledo was chosen because it was close to the northern terminus of the railroad from Calcutta, and was at the northern end of a caravan route out of Burma.

recommended building a road from Ledo, Assam, India, across northern Burma

to link up with the Burma Road. Ledo was chosen because it was close to the northern terminus of the railroad from Calcutta, and was at the northern end of a caravan route out of Burma.

Winston Churchill called the project "an immense, laborious task, unlikely to be finished until the need for it has passed." The proposed route went through some of the toughest terrain in the world. Northern Burma included jungle covered mountains and swampy valleys. The mountains were formidable land barriers reaching heights of eight to ten thousand feet. The valleys were tropical rain forests where clearings were really swamps covered with elephant grass 8 to 10 feet tall. Add to that leeches, malaria bearing mosquitoes, typhus carrying mites and a six month monsoon season averaging 140 inches of rain. All complicated by the presence of a veteran Japanese force. Chinese troops would face the Japanese force in the North Burma campaign. To support them General Stilwell organized a Service of Supply (SOS) under the command of General Raymond A. Wheeler, a career Army Engineer who had won recognition as a road builder in the Argonne Forest campaign of World War I. Wheeler established Base Section 3 at Ledo and construction of warehouses, barracks, a hospital, and base roads was begun. SOS was responsible for construction of the road in India and Burma which began on 16 December 1942. On 28 February 1943 the Ledo Road reached the India-Burma border. In March, early monsoon rains poured down. The engineers were constantly wet, equipment skidded off into ditches, and even pack animals could not transport needed supplies. Airdrops became necessary to supply the road builders. Progress on the road was slow. On 17 October 1943, General Wheeler placed General Lewis A. Pick in charge of the road building effort. Pick had been in charge of the Missouri River Basin project and knew that drainage was the most important part of road building.  Due to the monsoons, the road had developed into a drainage project and "drainage was his business". Pick stated the road was going to be built, "rain, mud, and malaria be damned". Pick's driving force and the end of the monsoons allowed the road to be moved ahead at about a mile a day by November 1943. Progress slowed again, this time due to Japanese resistance. Besides the land and weather obstacles, the Engineers also had to deal with the Japanese. The road project was a balancing act between construction and warfare. As it pushed ahead the Japanese had to be forced back. Much of the offensive was led by General Stilwell commanding Chinese troops. Merrill's Marauders also pushed the Japanese back. After successes and setbacks, Myitkyina was finally taken 3 August 1944.

Due to the monsoons, the road had developed into a drainage project and "drainage was his business". Pick stated the road was going to be built, "rain, mud, and malaria be damned". Pick's driving force and the end of the monsoons allowed the road to be moved ahead at about a mile a day by November 1943. Progress slowed again, this time due to Japanese resistance. Besides the land and weather obstacles, the Engineers also had to deal with the Japanese. The road project was a balancing act between construction and warfare. As it pushed ahead the Japanese had to be forced back. Much of the offensive was led by General Stilwell commanding Chinese troops. Merrill's Marauders also pushed the Japanese back. After successes and setbacks, Myitkyina was finally taken 3 August 1944.

Road construction proceeded with Chinese engineers out front, clearing a trace, followed by American engineers bulldozing the roadbed. Next an Aviation battalion cleared the right-of-way to a width of one hundred feet. Other companies were responsible for grading the road, placing culverts, and constructing the necessary bridges. Finally, gravel was spread for the final road surface. The completed road also had to be maintained. There were constant washouts, mudslides, and other problems, mostly due to the monsoons. Engineers worked to correct the problems and keep the road open. By early January 1945 the 465 mile long Ledo Road had been linked to the old Burma Road to complete the 1,079 mile land route to China. General Pick led the first convoy on 12 January 1945 from Ledo to Kunming China. Along were reporters and members of units that had built the road. The convoy reached Kunming on 4 February 1945. On 20 May 1945, Pick formally announced completion of the Ledo Road, calling it the toughest job ever given to U. S. Army Engineers in wartime. At the suggestion of Chiang Kai-shek it was renamed Stilwell Road, but was known to the engineers who built it as "Pick's Pike". Presently both the Ledo and Burma Roads are mostly in a state of disrepair, having long ago lost their importance. Some parts are in use and being upgraded. One part of the Ledo Road goes through Burmese jungle "uninhabitable by humans" and is now a wildlife refuge. Read More about and View Pictures of the Ledo Road. American Supply Services For the American supply services, their performance in the CBI Theater represented their finest hours. The tremendous distances, the difficult terrain, the inefficiencies in transport, and the complications of Indian politics presented formidable obstacles to efficient logistics.  Nevertheless, by early 1944, American logisticians had developed an

efficient supply system whose biggest problem was the time needed to ship

material from the United States. The supply services expanded the port

capacity of Karachi and Calcutta, enhanced the performance of India's

antiquated railroad system through improved maintenance and scheduling,

and developed techniques of air supply to support Chinese and American

forces in the rugged terrain of North Burma. Lend-Lease supplies shipped

from the United States arrived in Calcutta and Karachi, were then loaded on rail

cars, and sent north. In Ledo, supplies were sorted and warehoused until needed.

Supplies were then flown over The Hump to Kunming, China or air-dropped to front line forces in

Burma. Despite the skepticism of the

British and other observers, American engineers overcame the rugged

mountains and rain forests of North Burma to complete the Ledo Road which,

joined to the old Burma Road, together named Stilwell Road, reopened the line to China. Completion of

the Ledo Road allowed war materiel and other supplies to be trucked to

China, relieving the Air Transport Command of the difficult task of

flying everything over The Hump. Read more about

Supply Services.

Nevertheless, by early 1944, American logisticians had developed an

efficient supply system whose biggest problem was the time needed to ship

material from the United States. The supply services expanded the port

capacity of Karachi and Calcutta, enhanced the performance of India's

antiquated railroad system through improved maintenance and scheduling,

and developed techniques of air supply to support Chinese and American

forces in the rugged terrain of North Burma. Lend-Lease supplies shipped

from the United States arrived in Calcutta and Karachi, were then loaded on rail

cars, and sent north. In Ledo, supplies were sorted and warehoused until needed.

Supplies were then flown over The Hump to Kunming, China or air-dropped to front line forces in

Burma. Despite the skepticism of the

British and other observers, American engineers overcame the rugged

mountains and rain forests of North Burma to complete the Ledo Road which,

joined to the old Burma Road, together named Stilwell Road, reopened the line to China. Completion of

the Ledo Road allowed war materiel and other supplies to be trucked to

China, relieving the Air Transport Command of the difficult task of

flying everything over The Hump. Read more about

Supply Services.

The Hump  Japanese occupation of Burma in 1942 had cut off the Burma Road, the last land route by which the Allies could deliver aid to the Chinese Government of Chiang Kai-shek.

Until the Burma Road could be retaken and the Ledo Road completed, the only supply route available was the costly and dangerous route for transport planes over the Himalayas between India'a Assam Valley and Kunming, China. This route became known as the Himalayan Hump or simply The Hump. While the route kept the transports relatively free from enemy attack (Enemy action destroyed only seven aircraft, killing 13 men) it led over rugged terrain, through violent storms, with snow and ice at the higher altitudes the planes flew over the mountains. Flying the Himalayan Hump would turn out to be some of the most dangerous flying in the world. Over the course of action there were 460 aircraft and 792 men lost. Still, the operations were a success. There were 167,285 trips that moved 740,000 tons of material to support Chinese troops and other Allied forces. Read more about

Flying The Hump.

Japanese occupation of Burma in 1942 had cut off the Burma Road, the last land route by which the Allies could deliver aid to the Chinese Government of Chiang Kai-shek.

Until the Burma Road could be retaken and the Ledo Road completed, the only supply route available was the costly and dangerous route for transport planes over the Himalayas between India'a Assam Valley and Kunming, China. This route became known as the Himalayan Hump or simply The Hump. While the route kept the transports relatively free from enemy attack (Enemy action destroyed only seven aircraft, killing 13 men) it led over rugged terrain, through violent storms, with snow and ice at the higher altitudes the planes flew over the mountains. Flying the Himalayan Hump would turn out to be some of the most dangerous flying in the world. Over the course of action there were 460 aircraft and 792 men lost. Still, the operations were a success. There were 167,285 trips that moved 740,000 tons of material to support Chinese troops and other Allied forces. Read more about

Flying The Hump.

Map showing military airlift route over the Himalayas between Assam, India and Kunming, China, known as The Hump. Also shown is the planned route of the Ledo Road to connect to the Burma Road. The shaded area is Japanese occupied Burma. Merrill's Marauders  The Marauders, named after their commander Brigadier General Frank D. Merrill,

officially the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) and code named GALAHAD,

were 3,000 volunteer soldiers who marched and fought through jungles and over mountains from the Hukawng Valley

in northwestern Burma to Myitkyina on the Irrawaddy River.

In 5 major and 30 minor engagements they met and defeated the veteran soldiers of the Japanese 18th Division.

Operating in the rear of the main forces of the Japanese, they prepared the way for the southward advance of

the Chinese by disorganizing supply lines and communications.

The climax of the Marauders' operations was the capture of the Myitkyina airfield, the only all-weather strip

in northern Burma.

The 5307th Composite Unit was disbanded in August, 1944.

Members of the Marauders, along with Chinese units where then formed into the Mars Task Force.

Read more about

Merrill's Marauders

and a biography of

Frank D. Merrill.

The Marauders, named after their commander Brigadier General Frank D. Merrill,

officially the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) and code named GALAHAD,

were 3,000 volunteer soldiers who marched and fought through jungles and over mountains from the Hukawng Valley

in northwestern Burma to Myitkyina on the Irrawaddy River.

In 5 major and 30 minor engagements they met and defeated the veteran soldiers of the Japanese 18th Division.

Operating in the rear of the main forces of the Japanese, they prepared the way for the southward advance of

the Chinese by disorganizing supply lines and communications.

The climax of the Marauders' operations was the capture of the Myitkyina airfield, the only all-weather strip

in northern Burma.

The 5307th Composite Unit was disbanded in August, 1944.

Members of the Marauders, along with Chinese units where then formed into the Mars Task Force.

Read more about

Merrill's Marauders

and a biography of

Frank D. Merrill.

Supplying Merrill's Marauders Normal methods of supply were impractical for a highly mobile force operating behind the enemy's forward defensive positions. Any attempts to maintain regular land supply lines, even if adequate roads had been

Bamboo warehouses at Dinjan, 32 miles west of Ledo, were made available to the Marauders. Good air strips were nearby at Chabua, Tinsukia, and Sookerating. Arrangements were made for coded communication from General Merrill's headquarters to Dinjan through Combat Headquarters at Ledo. Eventually the base at Dinjan monitored all messages from General Merrill to Headquarters, thus eliminating the loss of time involved in relaying requisitions. Standard units of each category of supplies, based on estimated requirements for 1 day, were packaged ready for delivery. Requisitions were submitted on a basis covering daily needs or were readily adapted to this basis. At the beginning of the Marauders' operation the 2nd Troop Carrier Squadron and later the 1st Troop Carrier Squadron carried the supplies from the Dinjan base to forward drop areas. They dropped by parachute engineering equipment, ammunition, medical supplies, and food from an altitude of about 200 feet; clothing and grain were dropped without parachute from 150 feet. They flew in all kinds of weather. During March alone, in 17 missions averaging 6 to 7 planes, they ferried into the combat area 376 tons of supplies.  Where no open space or paddy field was available for the drop, it was necessary to prepare a field, but in the majority of cases the route of march and the supply requirements could be so coordinated that units were near some suitable flat, open area when drops were needed. This was an advantage, not only because it relieved the troops of the hard work of clearing ground, but because it enabled the pilots to use aerial photographs and maps to identify their destinations. The packages, attached to A-4 and A-7 parachutes, weighed between 115 and 125 pounds. Containers of this size were easily manhandled. As soon as they reached the ground, two of them were loaded on a mule and transported to a distributing point in a relatively secure area. There they were opened and the men filed by, each one picking up an individual package of rations or ammunition. Rations, wrapped in a burlap bag, contained food, salt tablets, cigarettes, and occasionally halazone tablets for purifying drinking water.

Where no open space or paddy field was available for the drop, it was necessary to prepare a field, but in the majority of cases the route of march and the supply requirements could be so coordinated that units were near some suitable flat, open area when drops were needed. This was an advantage, not only because it relieved the troops of the hard work of clearing ground, but because it enabled the pilots to use aerial photographs and maps to identify their destinations. The packages, attached to A-4 and A-7 parachutes, weighed between 115 and 125 pounds. Containers of this size were easily manhandled. As soon as they reached the ground, two of them were loaded on a mule and transported to a distributing point in a relatively secure area. There they were opened and the men filed by, each one picking up an individual package of rations or ammunition. Rations, wrapped in a burlap bag, contained food, salt tablets, cigarettes, and occasionally halazone tablets for purifying drinking water.

Careful planning, supplemented by speedy adoption of lessons learned from experience, paid big dividends in terms of efficient operation of the air supply system. About 250 enlisted members of the 5307th, including packers, riggers, drivers, and food droppers, were responsible for the job; everyone realized the importance of his role and felt a personal obligation to get the supplies to his comrades in the field at the time and place and in the quantities required. The high degree of mobility and secrecy which resulted from air supply was one of the chief reasons for the success of the Marauders. India-Burma In the spring of 1944 the Allies were finally able to attempt the reconquest of Burma. A force under General Stilwell fought down the Hukawang Valley and reached the vicinity north of Myitkyina, a key communications center and Japanese stronghold, in May 1943. Meanwhile, Merrill's Marauders had circled and were attacking Myitkyina from the south. Japanese resistance and the onset of the monsoon season in June delayed completion of the operation until August. As another phase of the spring offensive, a British force (the "Chindits") under British Major General Orde C. Wingate had made a successful airdrop near Kotha in March and proceeded to disrupt Japanese communications in central Burma. At the same time, farther to the south, a British Commonwealth force inflicted a considerable defeat on Japanese forces defending against a drive on Akyab, a port of the Bay of Bengal.  Meanwhile, in western Burma, the Japanese had launched a powerful, and very nearly successful, counterattack toward Imphal and Kohima in eastern India. The British made a last-ditch stand in the vicinity of Kohima and, when reserves arrived, won a decisive victory at the end of June 1944.

As the monsoon broke, the decimated Japanese force was in disorderly retreat back into the Jungles of Burma.

By late summer of 1944 the Allies had cleared northern Burma, permitting construction of the Ledo (or Stilwell) Road and a fuel oil pipeline from India to China.

Operations in Burma during the last year of the war were largely a British show. Actually, the British were more interested in recovering Singapore than in taking Burma or helping China, but American control of lead-lease, combined with an American policy that continued to back Chiang Kai-shek more or less dictated the reconquest of Burma.

The British would have preferred to accomplish the reconquest of Burma from the south, beginning with a seaborne assault on Rangoon, but demands on shipping for European and Pacific operations precluded such a plan. Consequently, the British attacked from India across the Irrawaddy River to Mandalay and then south to Rangoon. They experienced tremendous difficulties because of the terrain and the resistance of crack Japanese troops. Supply by air was essential to the success of operations.

Mandalay was captured after a prolonged fight in mid-March 1945. From then on progress to the south was relatively fast, and the reconquest of Burma was completed for practical purposes with the capture of Rangoon on 3 May 1945. Except for five Chinese divisions and a mixed American and Chinese brigade known as the Mars Task Force (replacing "Merrill's Marauders"), Allied forces in Burma consisted of British and British Commonwealth forces.

Read more about

India-Burma.

Meanwhile, in western Burma, the Japanese had launched a powerful, and very nearly successful, counterattack toward Imphal and Kohima in eastern India. The British made a last-ditch stand in the vicinity of Kohima and, when reserves arrived, won a decisive victory at the end of June 1944.

As the monsoon broke, the decimated Japanese force was in disorderly retreat back into the Jungles of Burma.

By late summer of 1944 the Allies had cleared northern Burma, permitting construction of the Ledo (or Stilwell) Road and a fuel oil pipeline from India to China.

Operations in Burma during the last year of the war were largely a British show. Actually, the British were more interested in recovering Singapore than in taking Burma or helping China, but American control of lead-lease, combined with an American policy that continued to back Chiang Kai-shek more or less dictated the reconquest of Burma.

The British would have preferred to accomplish the reconquest of Burma from the south, beginning with a seaborne assault on Rangoon, but demands on shipping for European and Pacific operations precluded such a plan. Consequently, the British attacked from India across the Irrawaddy River to Mandalay and then south to Rangoon. They experienced tremendous difficulties because of the terrain and the resistance of crack Japanese troops. Supply by air was essential to the success of operations.

Mandalay was captured after a prolonged fight in mid-March 1945. From then on progress to the south was relatively fast, and the reconquest of Burma was completed for practical purposes with the capture of Rangoon on 3 May 1945. Except for five Chinese divisions and a mixed American and Chinese brigade known as the Mars Task Force (replacing "Merrill's Marauders"), Allied forces in Burma consisted of British and British Commonwealth forces.

Read more about

India-Burma.

20th General Hospital After almost eight months of training at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, the unit consisting of nurses and enlisted men headed to San Franciso. They boarded the USS Monticello, as did my Dad, and on 20 January 1943 departed for India. After 42 days at sea with brief stops in New Zealand and Australia, they made their way to Ledo, finally arriving 21 March. Ledo, a tiny railroad town surrounded by the virgin jungle on the fringe of the tea plantations in the Assam region of northeast India would be home for the forseeable future.  The mountainous border with China was to the north and Burma (now Myanmar) lay on the east. At this time the Japanese invasion of China had forced the Chinese government into the interior, with Burma offering the only possible route of land communication between the Chinese and the Allies. To reopen communications with the Chinese, General Stilwell chose Ledo as the western terminus of his road into North Burma, to be built with the engineering and organizational skills of General Lewis A. Pick. As a huge military installation sprung up at Ledo, the 20th General Hospital took on the mission of providing medical care for the American-Chinese forces fighting the Japanese in Burma as well as for men constructing the Ledo road.

The hospital was constructed on higher ground around a former polo field. Native structures called "bashas" housed the hospital and its patients, nurses, doctors, and enlisted men. These bashas had dirt floors, sometimes covered with bamboo matting, and leaky roofs of palm leaves. There were no lights and very few outlets for water. In this area of heavy rainfall, malaria and bacillary and amoebic dysentery were constant; leeches and mites presented even more dangers than the snakes, tigers, elephants, bears, bison and rhinoceroses. In India doctors had to deal with battle casualties in an environment that not only made medical treatment difficult, but actually added to the problems.

Check in to the

20th General Hospital.

The mountainous border with China was to the north and Burma (now Myanmar) lay on the east. At this time the Japanese invasion of China had forced the Chinese government into the interior, with Burma offering the only possible route of land communication between the Chinese and the Allies. To reopen communications with the Chinese, General Stilwell chose Ledo as the western terminus of his road into North Burma, to be built with the engineering and organizational skills of General Lewis A. Pick. As a huge military installation sprung up at Ledo, the 20th General Hospital took on the mission of providing medical care for the American-Chinese forces fighting the Japanese in Burma as well as for men constructing the Ledo road.

The hospital was constructed on higher ground around a former polo field. Native structures called "bashas" housed the hospital and its patients, nurses, doctors, and enlisted men. These bashas had dirt floors, sometimes covered with bamboo matting, and leaky roofs of palm leaves. There were no lights and very few outlets for water. In this area of heavy rainfall, malaria and bacillary and amoebic dysentery were constant; leeches and mites presented even more dangers than the snakes, tigers, elephants, bears, bison and rhinoceroses. In India doctors had to deal with battle casualties in an environment that not only made medical treatment difficult, but actually added to the problems.

Check in to the

20th General Hospital.

|

A 1904 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Stilwell served in World War I as an intelligence officer for the Fourth Army Corps and was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his outstanding achievements. Stilwell was the military attache at the U.S. Embassy in Peking from 1935 to 1939 and became fluent in Chinese. Named chief of staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in 1942, Stilwell was the senior American military commander in the China-Burma-India theater during World War II. When Japan forced the Allied withdrawal from Burma in May 1942, Stilwell led a group of some 100 soldiers and civilians on a daring 140-mile march through the Burmese jungle and safely into India. Stilwell received his fourth star on Aug. 1, 1944, the same month Allied troops reclaimed northern Burma. The Burma Road was officially reopened in January 1945 and Stilwell was relieved as commander of CBI. After briefly commanding the Tenth Army in Okinawa, he returned to the United States. In 1945 Stilwell was awarded the Legion of Merit and the Oak Leaf cluster of the Distinguished Service Medal. In 1946 he was appointed commander of the Sixth Army in charge of Western Defense Command. He died 12 October 1946 in San Francisco, California.

Read more about

A 1904 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Stilwell served in World War I as an intelligence officer for the Fourth Army Corps and was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his outstanding achievements. Stilwell was the military attache at the U.S. Embassy in Peking from 1935 to 1939 and became fluent in Chinese. Named chief of staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in 1942, Stilwell was the senior American military commander in the China-Burma-India theater during World War II. When Japan forced the Allied withdrawal from Burma in May 1942, Stilwell led a group of some 100 soldiers and civilians on a daring 140-mile march through the Burmese jungle and safely into India. Stilwell received his fourth star on Aug. 1, 1944, the same month Allied troops reclaimed northern Burma. The Burma Road was officially reopened in January 1945 and Stilwell was relieved as commander of CBI. After briefly commanding the Tenth Army in Okinawa, he returned to the United States. In 1945 Stilwell was awarded the Legion of Merit and the Oak Leaf cluster of the Distinguished Service Medal. In 1946 he was appointed commander of the Sixth Army in charge of Western Defense Command. He died 12 October 1946 in San Francisco, California.

Read more about